The Calling

Authors: David B Silva

The Calling

David B. Silva

Copyright ©1990 David B. Silva

Originally published in

Borderlands

in 1990.

Also appeared in the collection,

Through Shattered Glass

,

published by Gauntlet Press in 2001.

Other Books by David B. Silva

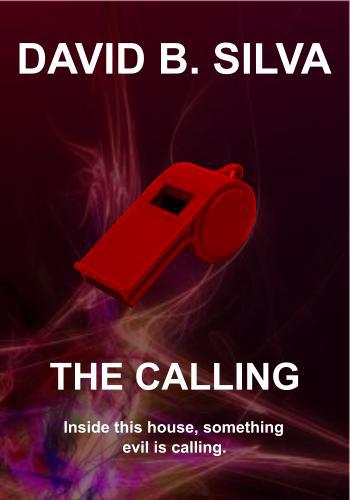

It never stops.

The whistle.

The sound is hollow, rising from a cork ball enclosed by red plastic. His mother no longer has the strength to blow had---the cancer has made certain of that---so the sound comes out as a soft song, like the chirring of a cricket somewhere off in another part of the house, just barely audible. But there. Always unmistakably there.

Blair buries his head beneath his pillow. He feels like a little boy again, trying to close out the world because he just isn’t ready to face up to what is out there. Not yet. Maybe never, he thinks. How do you ever face up to something like cancer? It never lets you catch up.

It’s nearly three o’clock in the morning now.

And just across the hall …

Even with his eyes closed, he has a perfect picture of his mother’s room: the lamp on her nightstand casting a sickly gray shadow over her bed, the blankets gathered at her feet. Behind her, leaning against the wall, an old ironing board serves as a makeshift stand for the IV the nurse was never able to get into mother’s veins. And the television is on. In his mind, Blair sees it all. Much too clearly.

He wraps himself tighter in the pillow.

The sound from the television is turned down, but he still thinks he can hear a scene from

Starsky and Hutch

squealing from somewhere across the hallway.

Then the whistle.

A thousand times he had heard it calling him … at all hours of the night … when she is thirsty … when she needs to go to the bathroom … when she needs to be moved to a new position … when she is in pain. A thousand times. He hears the whistle, the whirring call, coming at him from everywhere now. It is the sound of squealing tires from the street outside his bedroom window. It is the high-pitched hum of the dishwasher, of the television set, of the refrigerator when it kicks on at midnight.

Everywhere.

He has grown to hate it.

And he has grown to hate himself for hating it.

An ugly thought comes to mind:

why … doesn’t she succumb? Why hasn’t she died by now?

It’s not the first time he’s faced himself with this question, but lately it seems to come up more and more often in his mind. Cancer is not an easy thing to watch. It takes a person piece by piece …

“

My feet are numb.”

“

Numb?”

“

Like walking on sandpaper.”

“

From the chemo?”

“

I don’t know.”

“

Maybe …” Blair said naively, “maybe your feet will feel better after the chemo’s over.” He had honestly believed that it would turn out that way. When the chemo stopped, then so would her nausea and her fatigue and her loss of hair. And the worst of the side effects

had

stopped, for a while. But the numbness in her feet … that part had stayed on, an ugly scar left over from a body pumped full of dreadful things with dreadful names like doxorubicin and dacadbazine and vinblastine. Chemicals you couldn’t even pronounce. It wasn’t long before she began to miss a step here and there, and soon she was having to guide herself down the hallway with one hand pressed against the wall.

“

Sometimes I can’t even feel them,” she once told him, a pained expression etched into the lines of her face.

She knows, Blair had thought at the time. She knows she’s never going to dance again. The one thing she loves most in the world, and it’s over for her.

The heater kicks on.

There’s a vent under the bed where he’s trying to sleep. It makes a familiar, almost haunting sound, and for an instant, he can’t be sure if he’s hearing the soft, high-pitched hum of the whistle. He lifts his head, listens. There’s a hush that reminds him of a hot summer night when it’s too humid to sleep. But the house seems at peace, he decides.

She’s sleeping, he tells himself in a whisper. Finally sleeping.

For too long, the endless nights have haunted him with her cancerous likeness. She is like a butterfly: so incredibly delicate. She’s lying in bed, her eyes half closed, her mouth hung open. Five feet, seven inches tall and not quite ninety pounds. The covers are pulled back slightly, her nightgown is unbuttoned and the outline of her ribs resembles a relief map.

She’s not the same person he used to call his mother.

It’s been ages since he’s seen that other person. Before the three surgeries. Before the chemotherapy. Before the radiation treatments. Before he finally locked up his house and moved down state to care for her …

She cried the first time she fell. It happened in her bedroom, early one morning while he was making breakfast. He heard a sharp cry, and when he found her, her legs were folded under like broken wings. She didn’t have the strength to climb back to her feet. For a moment, her face was frozen behind a mask of complete surprise. Then suddenly she started crying.

“

Are you hurt?”

She shook her head, burying her face in her hands.

“

Here, let me help you up.”

“

No.” She motioned him away.

He retreated a step, maybe two, staring down at her, studying her,

trying

to put himself in her position. It occurred to him that she wasn’t upset because of the fall---that wasn’t the reason for the tears---she was crying because suddenly she had realized the ride was coming to an end. The last curve of the roller coaster had been rounded and now it was winding down once and for all. No more corkscrews. No more quick drops. No more three-sixties. Just a slow, steady deceleration until the ride came to a final standstill. Then it would be time to get off. The fall … marked the beginning of the end.

It had been a harsh realization for both of them.

He began walking with her after that, guiding her one step at a time from her bedroom to the kitchen, from the kitchen to the living room, from the living room to the bathroom. A week or two later, she was using a four-pronged cane. A week or two after that, she was using a wheelchair.

Everything ran together those few short weeks, a kaleidoscope of forfeitures, one after the other, all blended together until he could hardly recall a time when she had been healthy and whole …

She’s going to die.

Blair has known this for a long time now.

but …

how long is it going to take?

It seems like forever.

A car passes by his bedroom window. It’s been raining lightly and the slick whine of the tires reminds him of that other sound, the one he’s come to hate so much. He hates it because there’s nothing he can do now. There’s no going back, no making things better. All he can do is watch … and wait … and try not to lose his sanity to the incessant call of the whistle.

He bought the whistle for her nearly two and a half weeks ago in the sporting goods section of the local Target store. A cheap thing, made of plastic and a small cork ball. She wears it around her neck, dangling from the end of a thin nylon cord. Once, when it became tangled in the pillowcase, she nearly choked on the cord. But he refuses to let her take it off. It’s the only way he has of keeping in touch with her at night. Unless he doesn’t sleep. But he’s already feeling guilty about the morning he found her sleeping on the floor in the living room …

When he went to bed---sometime around 1:30 or 2:00 in the morning---she’d been sleeping comfortably on the couch, and it seemed kinder not to disturb her. Seven hours later, after dragging himself out of the first sound night’s sleep in weeks, he found her sitting on the floor.

“

Jesus, Mom.”

She was sitting in an awkward position, her legs folded sideways, one arm propped up on the edge of the couch, serving as a pillow. No blanket. Nothing on her feet to keep them from getting cold. And to think---she had spent the night like that.

He knelt next to her.

“

Mom?”

Her eyes opened lazily. It wasn’t terribly rational, but he held out a distant hope that she’d been able to sleep through most of the night. “I’m sorry,” she said drowsily. “I couldn’t get up … my legs wouldn’t …”

“

I shouldn’t have left you out here all night.” He managed to get her legs straightened out, to get her back on the couch, under a warm blanket, with a soft pillow behind her head.

That afternoon, he bought her the whistle.

“

When you need me, use the whistle. You got that?”

She nodded.

“

Night or day, it doesn’t matter. If you need me for something, blow the whistle.” He paused, hearing his own words echo through his mind, and a cold, shuddering realization swept over him. He didn’t know when it had happened, but somewhere along the line they had swapped roles. He was the parent now, she the child.

“

What if I can’t?”

“

Try it.”

Like everything else, her lungs had slowly lost their strength over the past few months, but she was able to put enough air into the whistle to produce a short, high-pitched hum.

“

Great.”

That was – what? – three weeks ago?

Blair sits up in bed. The streetlight outside his window is casting a murky, blue-gray light through the bedroom curtains. The room is bathed in that light. It feels dark and strangely out of balance. He fluffs both pillows, stuffs them behind him, and leans back against the wall. Across the hall, the light flickers, and he knows the television is still on in his mother’s room. It seems as if it’s far away.

He shudders.

Let her sleep, he thinks. Let her sleep forever.

Sometimes the house feels like a prison. Just the two of them, caught in their life and death struggle. The ending already predetermined. It feels … not lonely, at least not in the traditional sense of the word … but …

isolated

. Outside these walls, there is nothing but endless black emptiness. But it’s in here where life is coming to an end. Right here inside this house, inside these walls.

The television in her room flickers again.

Blair stares absently at the shifting patterns on the bedroom door across the hall. He used to watch that television set while she was in the bathroom. Sometimes as long as an hour, while she changed her colostomy bag …

“

I’ll never be close to a man again,” she told him a few months after the doctors had surgically created the opening in the upper end of her sigmoid colon. The stoma was located on the lower left side of her abdomen. “How could anyone be attracted to me with this bag attached to my side? With the foul odor?”

“

Someone will come along, and he’ll love you for you. The bag won’t matter.”

A fleeting sigh of hope crossed her face, then she stared at him for a while, and that was that. She hadn’t had enough of a chance to let it all out, so she kept it all in. The subject never came up again. And what she did on the other side of the bathroom door became something personal and private to her, something he half decided he didn’t want to know about anyway.

If he had a choice.

“

How’re you doing in there?” he asked her late one night. He’d had to help her out of bed into the wheelchair, and out of the wheelchair onto the toilet. That was all the help she ever wanted. But she’d been in there, mysteriously quiet, for an unusually long time.