The Case for Copyright Reform (5 page)

Read The Case for Copyright Reform Online

Authors: Christian Engström,Rick Falkvinge

But according to ACTA, the film or record companies would no longer have

to prove that they have actually lost the money. All they need to do is to

multiply the number of songs with the price for one song to get the amount of

damages measured by the suggested retail price.

A half million euro claim against a teenager with a 2 TB disk would be

considered disproportionate and absurd by any European court today. With ACTA,

awarding those damages becomes mandatory.

The copyright lobby knows this, or course. They have been deeply

involved in the ACTA negotiations since day one. It is only the citizens and

the elected members of parliaments that have been kept in the dark for as long

as possible. The plan was to get ACTA signed, sealed, and delivered before too

many elected politicians in parliaments knew the real consequences of ACTA as

well.

We must now make sure that that plan does not work.

Due Process

In Sweden, with nine million inhabitants, about ten people get struck by

lightning every year, and one or two of them die. This is of course very

tragic, but this one-in-a-million risk is not enough to make people think that

they themselves will get struck by lightning, and it is not enough to make them

modify their behavior in any significant way. You will not see anybody wearing

a protective hat with a lightning conductor if you walk down the streets of

Stockholm.

Before 2011, the risk of getting convicted of illegal file sharing was

about as high as the risk of getting killed by lightning. It happened at most

to one or two people per year, so it was not something that anybody would

seriously expect to happen to themselves.

In 2011, with three special prosecutors and ten police investigators focusing

on file sharing crimes,

the number of

convictions went up to 8

. Put in another way, this rather massive

deployment of scarce judicial resources (which could otherwise have been spent

on other crimes) only managed to get the risk of getting convicted for file

sharing up to the risk of getting struck by lightning, as opposed to getting

struck and killed. This is a considerable increase, but it is not enough to

make file sharers modify their behavior in any significant way. Some may take

the (sensible) precaution of spending five euros per month for an anonymizing

service to hide their IP number, but a potential risk at the same level as the

risk of getting struck by lightning will not make anybody stop sharing files.

To put the number of convictions in perspective,

Swedish news

agency TT reported

that about 20% of the Swedish population, or 1.4

million people, are file sharing according to national statistics. About one

third of them, or about half a million Swedes, are estimated to do it at a

level that would render them prison sentences if they were found out. But of

course, the vast majority of them never will be.

“We would need thousands of prosecutors”

one of the three special file sharing prosecutors

told the news agency, in full knowledge that this will never happen.

From the big film and record companies’ perspective, using the courts to

provide deterrence simply doesn’t work. Deterrence has no effect unless the

risk of getting caught is larger than microscopic. It isn’t today. The judicial

system does not have the capacity to bring entire generations to court at the

same time. Cases going through the system are burdened with way too much debris

like “evidence”, “due process”, and other red tape to create the volumes that

the film and record companies need to ascertain effective deterrence.

Unfortunately, they have realized this.

Therefore, they wish to make this whole process more efficient. In the

US, their wishes have largely come true. The reason that the Jammie Thomas case

got media attention wasn’t that it was the first, or that the claims made by

the record company were unusually outrageous. Those were exactly the same

claims that the record companies had already made in thousands of similar

cases. The Jammie Thomas case got attention because she was the first defendant

that pleaded not guilty, and stood up to the music and film industry

associations. Instead of folding and paying the offered settlement, she took

this case to court.

Let’s recap the numbers: The record company sued Thomas for $3.6

million, but offered a settlement out of court for $2,000. It is not difficult

to understand why most people simply pay up, even if they are innocent. The

mere threat of a costly court case and the risk of losing millions outweigh the

relatively minor cost of a settlement. It’s often smarter to just pay the

blackmailer and move on.

Yes, blackmail. Organized blackmail. That is what this is all about. US

record companies has sued 80-year old grandmothers, people with no computers

and, in a few cases, long-dead people. By forcing ISPs to giving up customer

records, these mass-mailed threats have evolved to a large industry in itself.

There’s no reason to be particular about who receives the threats, just send

them out and wait for the protection money to roll in. There is no incentive to

make sure that the defendants are actually guilty of anything, since the record

companies never stand to lose anything.

The key to this strategy for the rights holders is that they can force

the Internet service providers to disclose the name of the customer behind a

certain IP number that is used on the Internet. If they have this, they can turn

copyright enforcement from a cost to a profit center in its own right. Since

only a small fraction of citizens who get a threatening legal letter are

prepared to take the risk, and have the resources, to oppose it in court, the

limited number of cases that the court system can process per year is not a

problem for the scheme to work. To the rights holders, it’s free money in

exchange for a postage stamp.

The extent of this practice in Europe varies between the member states.

In 2010,

Danish film

maker Lars von Trier made more money from threatening to sue people

for allegedly downloading his film “Antichrist” illegally, than he got from box

office returns and video and DVD sales combined. The business idea was

completely straight-forward. All he had to do was to send out letters saying

“pay us 1,200 euro immediately, or we’ll sue you for five times that amount”.

Over 600 German recipients of the letter were sufficiently scared by the threat

of a costly legal process to pay up. Even if some of them were in fact

innocent, or if they just felt that 1,200 euro was a pretty unreasonable

punishment for having watched a movie (that wasn’t even particularly successful

at the box office) for free, they decided it was not worth the risk to have

their day in court.

Sweden, on the other hand, has so far mostly been spared this type of

behavior by the rights holders. This is because we used to have laws that

prevented the Internet service providers from disclosing information about

which of its customers had a certain IP number at a certain time, according to

Swedish data protection laws. Instead, the film and record companies have had

to file a criminal complaint and let the police investigate if a crime has been

committed. This is not enough for the rights holders, since the criminal

justice system does not have the capacity to get the volumes up to the level

that the rights holders want.

This may change, however, now that Sweden has implemented the

Intellectual

Property Rights Enforcement Directive

“IPRED”, and is working to

implement the

Data

Retention Directive

as well. These two directives were designed from

the outset to work in tandem, in order to give rights holders the practical

means to implement the strategy of legal threats.

The Data Retention Directive forces the Internet service providers to

keep logs that connect an IP number to one of their customers, and the Ipred

directive is intended to ensure that the rights holders and their anti-piracy

organizations can demand to get access to the information. If implemented the

way the rights holders want them to be, these two directives together open up

the door for US-style legalized blackmail of ordinary citizens.

The fundamental problem is that if laws have the effect of enabling

private companies to set up their own enforcement system where the vast

majority of cases are handled outside the courts, citizens can no longer expect

due process to be observed. The important thing is not what might happen in the

court of last instance, but the cost of getting there. If you as a citizen

cannot afford to take the risk of having your case tried in a proper manner,

you are being denied justice in practice.

...And It Isn’t Working Anyway

In June 2010, I (Christian Engström) attended a working group meeting on

copyright enforcement in the European Parliament. As guests, we had

representatives from the Motion Picture Association MPA, and from the record

producers’ organization IFPI. These two organizations represent the hard core

of the copyright lobby.

The representative from IFPI talked about how many fantastic things the

record companies would put on the market, if only online piracy could be

eliminated or reduced. To achieve this, she was asking for information

campaigns aimed at Internet users, and stricter sanctions against copyright

infringers.

She showed a slide with the words

“The music industry favours an approach

which combines the information of Internet users, with sanctions for persistent

infringers.”

This is exactly what the copyright industry always says, and has been

saying for over a decade. Information campaigns about copyright directed at

Internet users, and sanctions handed out by the Internet service provider

companies, preferably without any involvement of courts.

But leaving all other aspects aside, do we have any reason to think that

this will be effective?

When it was my turn to ask a question, I reminded IFPI and the MPA that

they have more than a decade’s experience of this strategy, in both the US and

Europe. It was in 1998 that

DMCA

,

the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, was adopted in the US. In Europe we have

seen a number new laws for stricter enforcement being introduced over the

years, notably the 2001

Copyright Directive

EUCD, and the 2004

Intellectual

Property Rights Enforcement Directive

IPRED. We have also seen a

number of information campaigns, often saying that “file sharing is theft”.

With so much experience from a number of countries, the rights holder’s

organizations are of course in a very good position to judge how effective the

strategy has been.

”Could you tell us about these experiences,

and could you give any examples where illegal file sharing in a country had

been eliminated or greatly reduced by information campaigns and sanctions?”

I asked the representatives from IFPI and the MPA.

The representative from IFPI said that so far, the strategy had not been

very successful. This was because the rights holders are forced to go through

the courts to punish illegal file sharers, which severely restricts the number

of cases they are able to pursue.

IFPI and the other rights holders would need to make a more wide-scale

mass response in order to create an effective deterrent, she said. She was

hoping that the EU would come to the rescue with legislation to allow this.

When it came to giving an example of a country where stricter

enforcement had led to significantly reduced file sharing, she mentioned

Sweden, where the IPRED directive was implemented on April 1, 2009.

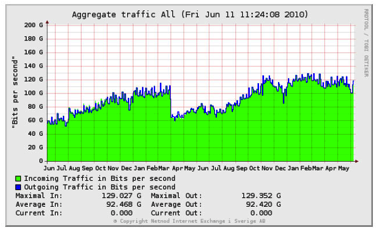

So let’s look at the graph for the total Internet traffic in Sweden

around that time: