The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter (88 page)

Read The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter Online

Authors: Kia Corthron

Tags: #race, #class, #socioeconomic, #novel, #literary, #history, #NAACP, #civil rights movement, #Maryland, #Baltimore, #Alabama, #family, #brothers, #coming of age, #growing up

Two minutes down the road the rain starts pounding. The boys get under the tarpaulin. Francis Veter turns on the windshield wipers, lights a cigarette, and glances at his watch.

“Only ten. Still plenty hours a dark.” He lets out an exhausted sigh. “Tie some bricks to it. Give it the right weight, we can send it floatin downriver without surfacin for miles. Or ever.” Randall remembers carp. Randall's brother-in-law fished in that river, shared the catch of the day with him and Erma, carp. “Well, like I said, no workin tomarra. I figured we'd be a little hungover.” A few moments pass before this last comment strikes Randall as outrageously funny. He starts laughing and can't stop. It becomes infectious, Francis Veter hooting as well. When the mirth finally subsides, Randall looks back at the truck bed, toward Eliot.

“We shoulda found out his name at least.”

“Ned the Nigger,” replies Francis Veter and they are roaring, splitting their sides, then Randall pukes out his window. He wipes his mouth. “Oooh, too much liquor.” Fifteen miles later the rain lets up, the sky clears. Randall looks back at Eliot. It occurs to him that they're driving in the wrong direction, getting further and further from the colored hospital. What if he's still alive? Randall turns around to face front, picking up a half-empty bottle of Jack near his feet. Twists off the top, lifts it, but as soon as the alcohol touches his lips he's puking out the window again, this time for a good ten minutes, every time the retching appearing it will stop it becomes heavier. When it's over he says, “I'll clean your door.”

“You damn sure will,” says Francis Veter, and it's his seriousness that sends them into gales again, Randall laughing and wiping tears and laughing and wiping tears and Randall is still wiping tears long after Francis Veter has gone quiet as they pull up along the banks of the river, the waters high and swiftly rushing after a long day and night of intermittent storms.

Â

2

It's nearly seven, just before daybreak, when Randall arrives home. All the lights in the house are on. He comes in through the kitchen. Erma and B.J. are there, both of them gaping at him. He is momentarily taken aback, then remembers he must look a sight, filthy and smelly, not to mention blood everywhere. Later she will tell him how frightened she was, waking up in a drenched bed (just a drenched pillow, Randall will think but not say), and she couldn't imagine where Randall could be so she called over to Benja's, where B.J. has been staying, to ask if her brother-in-law could come and wait with her.

Now Randall smiles and holds up a big, dead rabbit. “Hi, beautiful,” he says to Erma and drops the fresh game on the table. She's too shocked to utter a word (definitely a first), but Randall answers the question in her eyes, “Night huntin,” not bothering to sign it, which is to say he is ignoring B.J.'s presence. Without stopping, he walks through the house and up to the bathroom. When Erma regains her senses, he hears a blubbering tirade of “drunken fool” and “barroom brawl” but he is somewhere far away. He fills the tub and gets undressed. For a few minutes he gazes into the mirror at the blood handprint on his chest, then steps into the bath. As he washes himself, he looks at his clothing and shoes. He'll have to send Erma out on an errand today while he throws them into the furnace. Too bad he didn't buy an extra pair of Martin's on the discount when he had the chance. He'd shot four rabbits but gave the others to Francis Veter since he has all those kids, Randall who'd never before gone hunting was never interested in hunting went trigger-happy, everything that moved. The water is quickly saturated, grime and the red, so after cleaning himself thoroughly he drains the tub, scrubs it, draws another bath and scours himself again. When he steps out, another mirror inspection. The slash from his ear to his throat is still there, but shallow enough he anticipates it will heal soon enough. He descends the stairs wearing clean clothes, his washed hair combed and slicked back, teeth brushed. An hour since his homecoming and there Erma and B.J. still stand in the kitchen, Erma sobbing on B.J.'s shoulders. Though B.J. holds her comfortingly his mind is elsewhere, and he is staring straight at Randall when the latter enters. Erma hears something behind her and swerves around, but before she can lay into him again Randall goes to her, takes her hands, gently kisses each of her fingers and asks forgiveness for all the time he's been a bad husband, and she stares at him in disbelief as tears roll down her cheeks, and he tells her how much he loves her and has always loved her and he's never been the best mate but from now on he'll try, he'll really try and he wants to make a good life for her and he wants to make a baby and he wants to start now and she throws her arms around him and cries in joy and they walk off to the bedroom, arms around each other. B.J. stares after them, then quietly leaves.

The next day a picture appears in the local paper. A handsome young Negro leaning against an interior doorway, a closed-mouth but content smile. Indianapolis lawyer, he had been reported missing and the car he had been driving, a Plymouth station wagon, had been found upturned seven miles north of Prayer Ridge. The day after, Friday, the same picture is run again, but the implications of the accompanying article are much more sinister: a few teeth had been found fifty yards from the car. The distance renders unlikely the possibility that the injuries were incurred during the vehicular accident, and the notion that the injured man had managed to walk away now seems chillingly doubtful. B.J., just home from work, reads the item. His mother taps him, tells him Erma called asking if she could borrow a few eggs, could he run them over?

On Erma's coffee table, B.J. notices their copy of the paper, but is surprised to see that the article and photo regarding the missing Negro have been cut out. Erma says she has no idea why Randall had mutilated page five just as he had done yesterday. B.J. stares at the daily, something slowly dawning on him: that the night the man disappeared coincides with the morning Randall arrived home in his blood-soaked clothes, the morning Randall exhibited his bizarre behaviorâand suddenly B.J. is nauseated. As if on cue Randall walks through the door, returning from his second day at Oldham's Hardware. He stops short upon seeing B.J. with the paper, his eyes slowly dropping to the dismembered page then back up again at his brother's bewildered face, and Randall turns green. He looks to the floor, having trouble catching his breath, turns around, and walks back out.

Eight days later, Erma sits at Benja's kitchen table having coffee. “It's like everything I prayed for, like God brought it all at once. He been so lovin, an I think it's a really good job, he doin real good an. I think I'm expectin!”

“Aw.”

“I know that don't mean nothin, I been down at road

too

many times. But this one. I donno, like all the sudden our marriage is blessed, so this little one be welcomed into a happy home. I think that's what God was waitin for, I think this one gonna pull through!”

“Well I'm sure gonna pray for you all.” A commotion from the second floor. “YAW DON'T STOP FIGHTIN OVER IT I'LL GODDAMN COME UP AN TAKE IT FROM YA BOTH!” Silence.

“You want another cup?”

“I can get it.”

“Benja, you jus got out the hospital five days ago, you sit there an relax.”

Erma walks over to the stove, noticing the newspaper on the counter. “Ugh! How could they print that thing!”

“Tacky.”

“

Terrifyin!

Sickenin! you cain't even tell what it is. Monster.”

“They figger it been in the water ten days. Parently they set the time a death the day his people filed the Missin Persons report.”

“I was terrified when I picked up the paper this mornin! Some dream woke me middle a the night I couldn't go back, so sittin there in the kitchen when the paper hits the door. Got to grab it fore Randall gone scissors-crazy again, well now I know why he done itâtryin to protect me.” She shudders. “I thought some psycho was on the loose! You cain't even tell it's a nigger, firs glance I didn't know it was a lynchin.”

“Uh-huh.”

“I thought it was some psycho!”

“That's a mess though. You know where I stand regardin innegration but

that

is

uncalled

for.”

“So's comin down here where they don't belong,” says Erma, filling her cup with more milk than coffee.

B.J. has been living with his sister since she was released from the hospital, keeping a watch should her brutal husband show up. When he gets home from work at the sawmill, he walks up to the bathroom to wash before going into the kitchen to see if Benja needs any help with dinner. She waves him off. He picks up the newspaper. Two photographs, side by side. The previous picture of the smiling attorney, and to its right the ghastly disfigured remains just dredged from the river twenty miles south. The positive identification was made based on the remaining teeth of the corpse, which, like those found near the flipped station wagon, were determined to be those of Eliot Campbell. B.J. cannot tear his eyes away from the images, and Benja has to tap him three times before he notices.

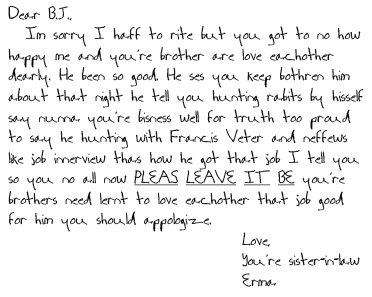

“Erma was here. She left a note.” Benja hands it to him, then dumps an entire stick of butter into a small pot of peas.

Â

Â

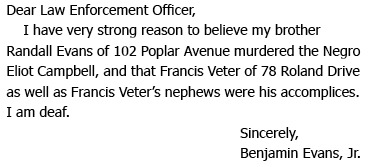

Had he been subpoenaed, perhaps his mother, sister, and even Randall would have understood, or tried to. But with not the remotest legal suspicion cast upon his brother, B.J. walks into the police station that evening and hands the dispatcher a note.

Â

Â

The specimens are so tiny as to have been missed even with meticulous cleaning by the suspects, but a bit of Eliot's blood is found in both Frances Veter's and Randall's trucks. Still, District Attorney Dylan O'Connor finds the case to be flimsy. In an already volatile atmosphere with the town enraged by the invasion of Northern lawyers stirring up local Negroes, he is now expected to prosecute local white men for the killing of one such intruder based on the minuscule samples of the victim's blood (a common type) coupled with the hunch of a deaf man with what is presumed to be a vendetta against his own brother. Yet under the pressure of the local NAACP backed by its umbrella national establishment, not to mention the fervent threats of the victim's Indianapolis law firm, O'Connor grudgingly indicts the accused, hoping to avoid another circus like the one that erupted around that Chicago boy killed in Mississippi five years ago. The court decides, given that Reginald Norris and Louis Norris are both under twenty-one, that they would be tried separately in a more lenient juvenile facility, though obviously a guilty verdict there would be contemplated only if the two adult defendants were found as such.

Respecting the constitutional right to a speedy trial, the jury of eleven white men and a white woman are selected the following week and the proceedings commencing the week after, Monday, November 14th. The key witness for the prosecution is Benjamin Evans Jr. Despite his initial reticence, the district attorney has professional integrity and, having brought the charges, plans to the best of his abilities to see them through to a verdict of guilty. So it's over his profound objections that the judge rules, for expediency, to bring in a sign-language interpreter to court rather than to have B.J. write notes. As he sits on the stand describing his brother's strange state of mind the morning after the murder, his clothing drenched in blood, something seems to be getting lost in the translation, partly because of the Evans brothers' raw version of the sign language and partly because the interpreter is a poor one. The only person in the room who fully understands what B.J. is trying to say is the one who taught him to sign, his brother, who sits next to Francis Veter behind the defense table, and at one point without thinking a desperately frustrated B.J. instinctively looks to Randall, as if his younger brother will translate as he always has done. Randall glares at his brother during the entirety of his testimony, not a blink. He wears his shirt buttoned to the top concealing the fresh wound B.J. had recently glimpsed and which, under oath, Randall will claim was a scratch from one of his night-hunting victim rabbits that was not quite dead. In trying to correct the interpreter's distortions, B.J. wildly waves his arms, and as it gradually becomes clear to everyone in the room, most of all to himself, that he will be dismissed as a mental defective, he points to Randall and cries loud enough and with such exaggerated enunciation that even the Negroes in the balcony clearly hear,

“I know he did it!”

Still, his deaf pronunciation causes titters from some of the whites and further clarifies that he is an unfit witness. At any rate his testimony is all circumstantial, as are the blood samples, claims the defense, reiterating O'Connor's concerns that the Negro's blood was hardly atypical.

It quickly becomes apparent that the judge and defense attorneys wish to have the trial over before the Thanksgiving break. So on Tuesday the 22nd the jury is excused to deliberate, and B.J. packs his suitcase. When the police came to arrest Randall two hours after his brother betrayed him, their sister and their mother flew into hysterics, begging the firstborn to recant. He could never bring himself to believe they would condone such an act, and yet they neither seemed anxious for justice to be served once the act was committed.

You have no proof!

and

What good would it do, ruin another life?

and

He's your brother!

What they never said because, B.J. believes, they didn't want to face the truth of it themselves, was

He didn't do it!

When he offered no reply to their beseeching other than to shake his head, his eyes barely, wistfully meeting theirs, they finally threw him out into the street.

Since then, two and a half weeks ago, he has been renting a room from an elderly woman near the center of town. He looks at the space one last time, the bed he made this morning that had afforded him barely a wink of rest since his arrival, the first time in his heavy-sleeper life he had ever struggled with insomnia. He clicks shut his valise, full of the few possessions he will take with him, and brings it, along with the two letters, downstairs to his landlady's kitchen, the wood-burning stove she would sometimes ask him to help her light. The first missive was from the Klan, or so it claimed, guaranteeing a swift end to his life should he testify. There had been one incident that had put that threat into action. B.J. would go to court every day, enduring the anonymous shoves and sporadic punches on his way to sitting in the front row far right, close enough, as best he could, to read the lips of the witnesses. It had been an especially bleak day for the prosecution when a physician claimed that it was possible Eliot Campbell had committed suicideâthe burns, amputations, castration self-inflicted, the broken bones and comprehensive organ damage the result of the body slamming against rocks after the man flung himself into the riverâthe motivation of which, the doctor speculated, could have been personal depression or some mad kamikaze

effort to vilify Southerners by making his death

look

like a lynching. The lunatic's proposition was met by gratified applause from most of the white spectators, and this was about all B.J. could take. At the lunch recess he found himself walking alone in a deserted alley, away from any sign of loathsome humanity. Someone with a crowbar running up from behind, apparently having assumed a deaf man would be an easy ambush but having not factored in the angle of the sun at that time of day nor anticipated the magnitude of his victim's boiling inner rage. B.J. had glimpsed the shadow and turned around, seizing the weapon and with his bare fist struck the man down with one blow, instantly poising himself for the next. The goon-turned-target gathered his wits rapidly and sprinted away with a bloodied and likely broken nose.