The Chamber in the Sky (10 page)

Read The Chamber in the Sky Online

Authors: M. T. Anderson

Instead, no one talked. Gregory wanted to ask what “brioche” was, but there was no way he was going to reveal to Gwynyfer that he didn't know a word. Angrily,

he ordered breast of branf and a triple-layer chocolate mousse cake.

Outside the circle of sidewalk tables, the heraldic bacterium hopped excitedly from claw to claw and flung himself into the air for little spins on his wings at the sight of their food.

Brian announced, “I have a name for the bacterium.”

“You're going to

name

it?” Gwynyfer protested. “Do you name your

body lice

?”

Brian said proudly, “Tars Tarkas.”

“Huh?” said Gregory.

Slightly bashful, Brian explained, “Tars Tarkas the Thark. It's the name of my favorite six-limbed character from literature.”

Gregory snorted. “I think it's not literature if there are characters with six limbs. That's one of the rules.”

Brian said defensively, “And I don't

have body lice

.”

Gwynyfer suggested, “Well maybe if you call their pet names loud enough they'll come back.” Then she repented and said, “I'm sorry, Bri-Bri. I forget you saved the fam. And us, too. Our hero. We are, of course, frightfully thankful.” She reached over and patted his hand. “You can call your vermin whatever you wish.”

Gregory gave Brian a hard, knowing look. It said:

You didn't save anyone's family. You accused them of murder.

Brian turned his eyes toward his entrée.

The lesser Volutes were a strange and creepy place. The ridge of cartilage surrounding the cavernous entrance was carved into a frowning, fanged face ringed with garlands of flowers. Once the wagon rolled through that gate, the three kids were in dark tubes branching in every direction. At the major crossroads, travelers had carved village names and arrows into the walls.

The thombulants wore huge electric lamps strapped to their backs so the kids could see where they were going. The beasts ambled up and down through the black, looping intestines, pulling the covered wagon behind them.

When they came upon a hut or a village, Brian would get out and ask if anyone had seen the Umpire Capsule. No one had.

They talked to shepherds who wandered through the intestines with their flocks of red sheep grazing on the mosses that grew on the walls. One of the shepherds had heard a story of something like the capsule being carried through the dark caverns of the Volutes, but he didn't know anything more.

They stopped for lunch with the shepherds. Brian had to distract Tars Tarkas so he wouldn't chase the flock. He and the germ played fetch. Tars Tarkas was so happy, his tail twitched with joy. He scampered under the legs of ewes, whirring and clicking with the thrill of the chase. Brian smiled and watched his weird pet fly up and catch twigs thrown in the air. Tars flew back and forth over their heads.

When they were done eating, they left the flock behind.

As they traveled along into the dark, they encountered fewer and fewer Norumbegans.

On the second day of wandering through the Volutes, they came upon a village that had been burned. The huts had been made of junk in the first place: bedsprings, crates, and loose rubble. Now everything was charred. Holes had been kicked in the walls.

No one was there.

“The Thusser raiding parties,” Gwynyfer whispered. “Bad show.”

From then on, everything they encountered was abandoned and ruined.

They could not tell whether it was day or night anymore. They rarely encountered veins of lux effluvium. The landscape, therefore, was just miles of dark, winding intestine. They slept once. The thombulants slept, too, and blew steam out of their vents.

Gregory sat apart from Gwynyfer. He did not speak much to her. Brian watched them. He wondered why they fought. Gwynyfer did not seem angry, but she did not speak much. None of them did.

Eventually, they came upon a village built on a rise near a bulging vein full of glowing lux effluvium. The vein was fading for the night. The village was made entirely of old rubber tires in stacks, like black, dirty igloos with tin roofs.

No one seemed to be around. Just old machines, abandoned oil drums, and car parts. The wagon rolled slowly into the circle of radial tire dwellings.

“Tars is frightened,” whispered Brian. The bacterium

was crouched on top of the wagon's canopy, flicking his head back and forth.

“Maybe he smells disinfectant,” Gwynyfer said unkindly.

But Gregory was also looking cautious.

And then doors began to open.

Things began to come out.

They were not human. They were not Norumbegan. They were complicated and feathery or leafy. They moved on stalks.

They surrounded the wagon.

I

n New Norumbega, the Mannequin Army was worried. Several of the other hearts in the Great Body's cluster were now beating irregularly, and every six or seven hours, a tremor would shake New Norumbega. This did not make it easy to build walls through the streets of the ruined town.

The tremors also uncovered things. The heaped, broken palace slid and crumbled. One day, a group of mannequin workers moving rubble sent for General Malark. They said they'd found something that looked important.

The general and Kalgrash climbed across the broken expanses of concrete and burnt wood.

“They say it was uncovered in the last earthquake,” Malark explained.

Kalgrash shook his head. “These earthquakes make me nervous. Nervous, nervous, nervous. They're getting bigger. I don't like this Great Body moving.”

“You should have seen it during the Season of Meals,

Kal. Things shooting through all the passages. Everyone washed away. It was awful.”

The troll said, “I'm telling you, we should all just abandon this place. Soon as the Thusser are knocked out of the Game.” They climbed down into a pit. “What is it the workers found down here?” Kalgrash asked.

“They don't know. It's a room that was lost somewhere in the palace. The ruins just showed up when the debris shifted.”

Lamps lit a cave in all the jumbled trash and the remains of walls and floors.

Kalgrash and Malark ducked and went in.

It was half of a room. The ceiling had fallen and crushed the other half. In this half, there were big, old, yellowing computers, a dot matrix printer, and stacks of old printouts bound into books. On the wall was a poster that showed the Emperor Randall leading off an ice-skating extravaganza. There were cables everywhere.

Kalgrash clicked the knob on a radio. It didn't go on. He followed the cord down behind the desk. It was plugged into the wall, but there was no power.

Malark was sorting through a huge, messy roll of paper that had long ago spilled out of the printer. “Look,” he said. “Some kind of messages.”

Kalgrash went to his side. Malark held up a lantern and asked, “You've had reading installed, haven't you?”

“Yeah. Last week. English and Norumbegan.”

“Don't know if either of those will help you. It's in Norumbegan, but it's mostly abbreviations and numbers and ⦠I don't know.”

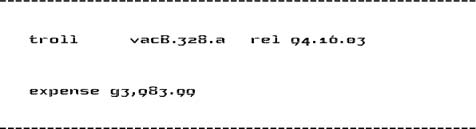

Kalgrash read several entries. They were dated, and talked of the Game. They announced players and winners and losers.

“It's from Wee Sniggleping,” said Kalgrash. “Friend of mine back on Earth.” He looked down at the mess of wires. “Is there any way to get electricity running through these units again? This looks like some kind of communication center. We should try to get it back in working order.”

“No reason we can't power it up,” said Malark. “But it will be harder to figure out where all the cables go.”

A soldier stepped forward. “Sir,” he said. “Nim Forsythe, sir. From the Corps of Engineers. I'm an electrician. The equipment is attached to a long piece of wire that must have been an antenna of some kind. With tiny writing on it. Magical writing.”

“I bet,” said Kalgrash. “It must have been able to transmit and receive across the barriers between worlds.”

Malark considered. “All right,” he said. “Let's move all this equipment into our section of the city. Carefully. And nothing gets taken apart without being diagrammed. When it's all set up there, we'll power up and see what we have.”

He ducked out of the low passage and went to issue orders.

Kalgrash looked back at the paper readout.

That was the day the Game had begun. A few months before that, he knew, he'd been built and activated. His memories went back years, but Wee Snig had admitted that Kalgrash was just a little over a year old. He flipped back through the pages of statistics and requests and numbers. He couldn't make sense of them.

But there, in a list on June 7th, was a line item:

He had no idea what the numbers meant, or the abbreviations

vac

and

rel

. He knew what

expense

meant. That was how much magic they'd spent activating him.

June 7th. He'd been born â activated â on June 7. He tried to remember that day. He couldn't recall anything in particular. He was never careful with a calendar.

The last summer had been a good one. Before the Thusser came. Very green, very humid. That summer, he'd

done a lot around the yard. He'd sat by the riverbank fishing. He'd made stews out of mushroom caps. Or at least that's what he remembered.

But he knew that one of those many days when he remembered walking to the top of Mount Norumbega for a fresh breeze and a view of eagles, it had actually been his first day alive. It must have been June 7th. That day, he supposed, he'd walked down the leaf-littered path from Wee Snig's workshop on the peak for the first time, and as he'd walked, he'd forgotten Wee Snig a little more with each step, and he'd remembered the warm lair under the bridge which, in reality, he had never seen before.

He had come home after his hike â he thought of it as home, and thought of his walk there as a hike â and he had pulled out ice tea that someone else had made and he had poured himself a glass. He had recalled stirring in lemon himself. That evening â who knew? It had been his first night alive, but it had seemed to him like a thousand others. Maybe he had watched the fireflies come out in the glades, winking like a vast computer console. Or maybe it had rained.

In the dark beneath the ruins, he stared at the record of his making and waited for the engineers to come.

Deep in the Volutes, in a town made of tires, heaped creatures stood by the doorways of their huts, unmoving, surrounding the kids' cart.

Brian scrambled to get out the rifle.

“Don't trouble yourself,” whispered Gwynyfer. “They're the fungal priests of Blavage.”

“The

what

?” said Gregory.

Gwynyfer had already stood up and was addressing the monsters. “The Honorable Gwynyfer Gwarnmore, daughter of His Grace Cheveral Gwarnmore, Duke of the Globular Colon, greets their ancient and holy presences, the fungal priests of Blavage; she requests audience and asylum.”

The largest of the mounds moved forward on its complicated, vegetable limbs and gestured gracefully that she should step down from the wagon.

She jumped off and then bowed.

The large mound spoke slowly and softly, as if its voice was not produced through a throat and mouth. It said,

The fungal priests do welcome you, brave animals, kind animals. Come rest. Take water.

“Won't say no,” said Gregory, and he hopped out of the wagon. To Gwynyfer, he whispered, “What's going on? Can you do, like, an introduction?”

She explained, “The fungal priests were here before the Norumbegans came. Not in this sad burg, but in Blavage. It's a spot in Three-Gut they've been living at for centuries. They're famous.” She asked them, “Why aren't you at your sacred circle there?”

Burned. Fire. Many are soil now. An animal walks in lines and ranks. An animal puts to the torch our kin. We come, bowed and bent, through uncommon ways and the path of nutriment and find now these huts, this haven. We begin again.

“Hi! I'm Gregory. I'm a person. It's great to meet you. Do you ever not talk like that?”

“Their Norumbegan isn't great,” Gwynyfer said. “But they're a very popular costume, as you can imagine. More popular than Thusser.”

Brian said, “I'm Brian. Did the Thusser destroy your ⦠your city or whatever? Your sacred circle? At Blavage?”

The belly fills with dire animals in dark fiber. Vessels eclipsed. The kind machines wind down and stop.

Gwynyfer asked the heap, “Would the fungal priests mind terribly if we stayed here and slept? The thombulants need to rest.”

Rest, indeed. We go about our chores. We pray to the Great Body. We pray, for the Great Body wakes.

“Yeah,” said Gregory. “We were wondering about that. Why does the Great Body have to wake right now?”

For minds in strife are within it. For there is unrest. For there is anger. It stirs. We pray for its return. We greet its coming nausea.

“That's super of you,” said Gregory. “Kids, let's grab the tents and eat the last of the cookie dough.”

They set up Gwynyfer's silk pavilion in the center of the village. It had little peaked roofs and pennants and beautiful rugs for her to lie on inside. Setting it up was

hot work. Brian and Gregory decided they'd just sleep outside in their sleeping bags. There was no chance of rain.

They sat on their sleeping bags â and Gwynyfer sat near them, on her tapestry cloth of gold â and they watched the fungal priests prepare for the evening.

The creatures danced around the village in the dying light of the lux effluvium. They had no heads, no top nor bottom, and so they danced with whatever branches were closest to the ground, spinning slowly, their fronds fluttering. A rich scent came from them, a hothouse smell, warm and green. This was, Gwynyfer said, their prayer. They exhaled scents to please the Great Body or stimulate it to growth.

Tars Tarkas the germ clearly did not like or trust them. He leaned against Brian, almost wrapped around the boy. He leaned particularly close when Brian ate some branf.

Brian watched the dancing and hated the Thusser for killing and burning these gentle and acrobatic growths. He couldn't stand the cruelty. It reminded him of the bullies who'd poked at his chub in grade school and slapped him from so many directions he dropped his books. It was like a world where those bullies were grown and now could kill with glee, with delight. He was furious.

He asked, “What did they mean about the strife in the thoughts of the Great Body?”

Gwynyfer said, “We don't know if the Great Body has a brain. No one has ever found it. It's possible that instead, it thrives on the thoughts of the creatures that live in it,

much, you know, in the way the Thusser use people's thoughts as manure. Gregory's thoughts, for instance. Gregory's thoughts were clearly good manure. A few disco lights and he was knocked out cold and ready to serve the Thusser masters.”

“Hey,” Gregory said, irked. “Not funny, okay?”

Gwynyfer continued, “So the fungal priests were saying that the strife the Thusser Horde has brought here is like a particularly interesting and difficult idea to the Great Body. Some kind of uneasy dream. It's stirring the Great Body. It might have woken it up.” She smiled. “Strife is life. Life is strife.”

They fell silent, then, and watched as the pious fungi performed their weird ceremonies at the dying of the light.

In a little while, they decided to go to sleep. The fungal priests were slowing down. Gwynyfer went into her silk pavilion, and they heard her arranging herself on her bed of pillows.

Brian felt small paddling feet on his legs, and realized that Tars Tarkas was curling up on his sleeping bag. He looked down at the insecty dragon. Tars Tarkas's beaky snout was resting on his front pair of claws while his tail and body wound around and around in a spiral. Brian liked the weight there on his knees. It was very reassuring. He liked the earthy smell of the creature, mixed with the deep, forested scent of the praying priests.