The Chemistry of Tears (13 page)

Read The Chemistry of Tears Online

Authors: Peter Carey

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Historical, #Cultural Heritage

“All men,” I said, “need money to live.”

“I am not making it for profit,” he said, “but because you love your son.”

“You also have a son,” I blurted. What made me say it, I have no idea. To stop him? To cancel him? In any case, I knew Carl was not his son.

“Are you blind?” he cried. “This boy is no one’s son. He is what these idiots would call an angel. If they knew the truth they would crucify him. Of course the ignorant father dragged him off in the middle of a riot. He might as well have offered up a Dresden bowl, he had no idea of the treasure. The universe is blessed that the child was not really cracked and broken. Beer,” he called, or words to that effect. “You do not want a duck,” he declared.

“You accepted my plan.”

“I am instructed to make something far superior.”

“It is I who instructs you.”

Then suddenly his manner was very soft and gentle. He laid his big hand on top of my arm and grasped it. “Henry,” he said. “We need each other.”

I have met men like this before, fierce, hard, rude, but capable of this swift seductive kindness. When he said our need was mutual I believed it was the truth. His eyes turned soft as silk inside their bony case. He leaned closer and, with that great hand still holding me, spoke softly. “What are you doing with your life? To what use is it put? What higher purpose do you serve?”

He would dominate and use me, so he thought. Alas, I must use him. “Dear Sumper,” I said, “you must make me the duck or I will make you very sorry.”

He stood suddenly. I thought, what now?

He would leave the inn. I with him.

“You are a sad man,” he said as we came out onto the muddy track. “You have suffered a loss.”

I thought, be calm, he cannot know that.

I followed him down off the saddle of the road, down into the clear under-forest. I thought, he is a fraud but I was, quite suddenly, hot all over.

As he walked, he belittled the fairytale collector, saying he was a simpleton who bought whatever stories the peasants invented for him in the winter. They were not real fairy stories at all. He however, he told me, had a twenty-four-carat fairy story. He was thinking he might trade it with the fairytale collector for something useful.

I thought, none of this is true. Also, I have not seen a single piece of clockwork, not an axle or a wheel.

He said, a mother had a little boy of seven years who was so attractive and good that no one could look at him without liking him, and he was dearer to her than anything else in the world. He suddenly died, and she could find no consolation …

I needed him. I let him talk.

“She wept and wept,” he told me. However, not long after he had been buried, the child began to appear every night at the very places he had sat and played while still alive. When the mother cried, he cried as well, but when morning came he had disappeared. The mother could not stop her weeping, and one night he appeared in the white shirt in which he had been put to rest.

To listen was a torture. Had I not been desperate for his services, I would have stopped his ugly mouth.

“He had the little laurel wreath still on his head. He sat down on the bed at her feet and said, ‘Oh, mother, please stop crying, or I will

not be able to fall asleep in my coffin, because my burial shirt will not dry out from your tears that keep falling on it.’ This startled the mother, and she stopped crying. The next night the child came once again. He had a small lantern in his hand and said, ‘See, my shirt is almost dry, and I will be able to rest in my grave.’ Then the mother surrendered her grief to God and bore it with patience and peace, and the child did not come again, but slept in his little bed beneath the earth.”

He was cruel and vile. I struck him on his big stone forehead, just beside the eye. He staggered. I kicked him in the groin. He doubled, letting out a girly shriek. Then I am afraid I became careless of my life for I knocked him and kicked his great meat carcass until he made no noise. What a lot of him there was, curled up amongst the mat of fir needles like a broken deer.

I was a fool. He had been my only hope. I returned to the inn and went to sleep.

MY TEMPER WAS RARE

and awful, as frightening as a plunging horse that is better shot than fed. It had never helped me, never once. In this case, I was very lucky I had not murdered Sumper.

Next morning I dressed, doing up my buttons with swollen hands, already anticipating the nasty consequence of victory.

The girl brought my breakfast, but I could not eat, knowing only that I had made a mess of everything.

Then Sumper arrived and I was ashamed to see the raw colours of his cheeks, the almost naked bone, the damage I had caused the only person who could save my son.

When I left the inn he followed me wordlessly into the dark fir forest where I smelt my death. I anticipated the type of clearing where such matters are always settled. Low Hall, Furtwangen, it is all the same. Percy, I forsook thee.

We came to open farmland. The sun was reappearing in the western

sky. The white charlock, which was obviously as much of a pest in Furtwangen as is its yellow brother in Low Hall, touched the morbid scene with falsely cheerful light.

“Where do we go?” I asked. “Let us get the business done.”

I had cut his lip and caused his moustache to rise crookedly upon his face. When he rested his hand upon my upper arm, he seemed to leer, but I detected in this single act of gentleness his regret for what he was now required to do.

“Look,” said he, pointing to a man and two women emerging from a small church. He went to speak to them and I noted well the broad shoulders and terrifying neck. I had no rage, and therefore not the least will to attack him from behind. I thought, I must run away, no matter what a coward I seem. But then the young man kissed both women and all the poor creatures began to weep. Really, their pain was almost unbearable. The women were hardly able to hold themselves upright. They made their way into the forest, staggering and howling in the most awful way.

The man turned his eyes upon me and all I saw was dark and dry. Then, with a lingering look of hatred, he raised his bundle to his shoulder and walked down the hill.

“A clockmaker,” Herr Sumper announced as he returned. The young man swung his bundle from his back and slammed it angrily against a tree. “Poor chap,” he said and his injured face looked particularly ugly in its sentimentality. “But he fell into the hands of a packer.”

Enough. I had always known that the world was filled with millions and millions of hearts, like gnats and flies, each with its own private grief like this one. But where was my punishment to take place?

I asked, “What is a packer?” but I was more concerned with sizing up his mighty arms.

“It is the packers,” he said, “who buy up clocks from the poor families who make them. The makers must accept whatever mean price they are offered.”

I stopped and put my fists up. “Where are we going, damn you?”

“Damn me?” He grinned at me and slapped my hands aside.

All around me were the signs of good sane Germans who cared for their little plots, carried manure, mould, whatever disgusting thing that was needed. They were industrious. They were humble. They were wilful. They tilled the subsoil, hoed and weeded until they compelled fertility. Why did I have to deal with a maniac? I knew the answer. I was a fool to have forgotten it.

“When I was young,” he said, placing his hand on my shoulder and thereby, while affecting to be companionable, forcing me to walk beside him, “the packers used to make the round of the cottages and collect the clocks themselves. But now the vermin have grown fat. They compel the clockmakers to come calling on them. They keep them waiting. Of course they are mostly inn-keepers,” he added. “The longer they are kept waiting, the more beer they drink and that is all subtracted from the price.

“So the young men are forced to go to England. They leave their mother and their wife behind.”

There, at the bottom of the hill, beside a narrow little stream, I was truly sorry for the swollen brute. “Just like yourself,” I said.

He considered me a moment, as if amused, then turned his attention to the view. “Here is my wife,” he said.

Amongst the many, many fanciful and quite insane things Herr Sumper would later insist on—his ability to cause lightning storms for instance—this small comment has its own peculiar place, for his “wife” appeared to be nothing less than the so-called “dung heap”: Furtwangen, with its lanes exceeding narrow and irregular, with its winding streets, its curious old buildings, its wood-carvings, and its profusion of old-fashioned metal-work. The only flaw in the picture was the obtrusively ugly modern structure, rising high and level, and looking gravelly and prosaic.

“What is that building?” I asked him.

At which point, while I was off my guard, he lurched at me.

I struck his throat.

His eyes bugged.

I spat at him.

He took me in a bear hug so tight he crushed my lungs and forced from me a most unmanly squeak, lifting me up high, turning me clockwise, anticlockwise, then upside down, and back again upon the earth.

“Why,” cried he, as he kissed me on both cheeks, “it is where they make your springs.”

Thus I understood this madman intended—after all that I had said and done—to make the automaton. Then, out of sheer relief, that my sick child would truly live, I slapped his face.

Room 404 Annexe

3 May 2010

Present: E. Croft (Curator Horology), C. Gehrig (Conservator Horology), H. Williamson (Conservator Ceramics), S. Hall (Line Manager)

The purpose of the meeting was to decide a schedule for identifying, restoring, and reconstructing the automaton presently identified as H234.

It was decided that C. Gehrig would make an inventory of the automaton and present the findings to the Curator and the Ceramics Conservator in the last week of June. As the physical condition of this bequest is rather “pig in a poke” it was agreed that C. Gehrig and E. Croft (together, perhaps, with Development and Publicity) would meet before the August holidays to see where things stood. C. Gehrig asked if this object was primarily a “crowd-pleaser.” E. Croft said that “crowd-pleasers” had never been part of the museum’s mission. He added that although the budget for this restoration would be initially limited, he was not pessimistic about the future.

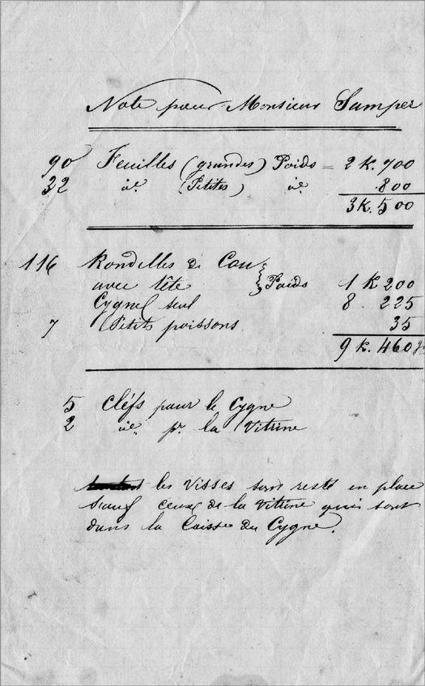

E. Croft then provided for the committee a receipt for weighed silver made out to a “Monsieur Sumper.”

The presence of glass rods and small silver fish gives some indication of the action. However it will require a full assessment to know the value (if any) of the swan both in an historical sense (c. 1854) and in terms of whatever use it may be to the Exhibitions Committee. It was clearly “early days.”

It was the Curator’s strong recommendation that the Conservators undertake this work in three stages.

1. assessment and identification.

2. restoration of the automaton and the accommodation of the clockwork within a newly produced pedestal or plinth à la Vaucanson. This would enable us to exhibit sometime in 2011 and would attract funds for stage two. The Conservator expressed her general agreement with this strategy.

3. restoration of the original chassis, which not only presents its own set of puzzles, but requires greater resources than the museum can contemplate at the present time.

The meeting shared the Conservator of Horology’s opinion that the assessment and identification could be conducted by a single Conservator in a timely manner.

S. Hall said that an assistant (graduate of both Courtauld and West Dean—young but highly recommended) could be made available almost immediately. E. Croft agreed to assess progress in ten days and discuss what resources might then be required.

Given the age of the automaton and its imperfect storage, C. Gehrig warned that it was likely both spring and arbor were dried out. Removal of springs from the spring barrel would require the manufacture of a wooden jig which would not be inexpensive, particularly as the work must be done off-site, at University College London. E. Croft will speak to the College and attempt to arrange a favourable price estimate. He stressed that although the budget for this restoration would be initially limited, he had great hopes of “turning on the taps.”