The Circus in Winter (17 page)

Read The Circus in Winter Online

Authors: Cathy Day

X Wallace Porter

Owner and Manager, the Great Porter Circus

X Edgar Coleman

President, Coleman Bros. Circus

The Jungle Goolah Boy's Story,

According to

Life

Magazine

Cook, Roger. "May All Your Days Be Circus Days,

"

Life.

July 30, 1940.

The big top provides many opportunities to the American Negro. For example, "Sugarchurch" (he did not divulge his real name) was a struggling sharecropper in South Carolina until he joined the circus at age 16. He started as a Pullman porter, worked his way up to animal handler, and eventually found himself working for various circuses in a number of different incarnations as "The Wild Man." Currently, he is trouping with Warren Barker's Wild Animal Odyssey as "King Kungo," but over the years, he's worked for the now-defunct Great Porter Circus, the Coleman Bros. Circus, and others, where he was billed under a variety of names: "Zumi the Monkey Boy," "Zootar the Missing Link," and "Jungle Goolah Boy." On average, he earns $30 a week, a sum he says far exceeds that which he can make elsewhere.

According to Mr. Sugarchurch: "They keep me in a cage most times in hardly no clothes, and I'm not to talk to folks, just grunt and look mean. When the people come to look, they throw me raw meat. I poke at it and smell it and worry over it, but I just pretend to eat it because it's horse meat mostly." When his sideshow duties were over, he donned a clean pair of dungarees and went directly to the cook tent to enjoy his real dinner: pork chops and mashed potatoes.

Chapter the LastAdvance departments often circulate bogus stories in small-town newspapers the week before the circus is scheduled to arrive to increase ticket sales. A common promotional tactic is to report that the wild man has escaped. The advance man for Warren Barker planted such a story in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. The day before the show arrived, the local paper announced that, after a weeklong manhunt, "King Kungo" had been captured by Canadian Mounties and was safely chained for his visit to Sioux Falls. Mr. Sugarchurch claims that in the many years he's worked as a wild man, he's "escaped" thousands of times.

How Sugar Church became the Jungle Goolah BoyâAccording to his BrotherâAccording to the WPA

Federal Writer's Project, WPA Life Histories

South Carolina Worker's Project

NAME OF WORKER

: Florence Place, Murrell's Inlet, S.C.

DATE

: September 10, 1938

FORM A

: Circumstances of Interview

- Subject: Negro Folklore and Migration.

- Name and Address of Informant: Marvin Church, Edisto Island.

- Place of interview: his home.

- Description of room, surroundings, etc.: Kitchen in three-room pole house, clay chimney. No electricity, meagerly furnished, but clean.

FORM B:

Personal History of Informant

- Ancestry: Negro.

- Place and date of birth: Eastwater plantation, March 10, 1882.

- Family: Married, eight children, five living.

- Occupations: drove a carriage until 1908, when Eastwater's owner died; moved to Edisto in 1908, makes living as ferryman.

- Special skills and interests: Mr. Church is a "sticker" with the Edisto Island Shouters.

NOTE

: "Shouts" are a remnant of the slave-song tradition incorporating call and response singing to the beat of a broom or stick on a wooden floor. Recorded by John A. Lomax. Songs, spirituals, hymns, including a narrative on the storm of 1893 spoken by Mrs. Ursula Brown. Recorded in Murrells Inlet, SC, August 1936. (See AFS 829â877. Two discs. Tape copy on LWO 4872 reels 59; 62â63.) - Description of Informant: medium/slightly built, weight about 155, skin heavily lined, the color of coffee with cream.

- Other points gained in interview: The subject spoke in a Negro dialect that was sometimes difficult to understand. I have translated somewhat for ease of reading.

Â

FORM C

: Text of Interview

I was born after slavery time. You can always tell those that come before. The blue hands for one, from tending the indigo pots. The "G" brand on the foot. The web on the back. That's what my brother and me called the whipping scars, spiderwebs. We wasn't to watch my daddy and uncles when they washed or changed shirts or shoes, but we always snuck a look when we could. I never saw my mama's bare back till she died, and she had the webs too, come to find out.

My daddy went to war with Master Grimm and cleaned his clothes and fed his horse. Got a minié ball in his calf and limped all his life. Master Grimm was thankful for all my daddy done and buried him with a nice headstone. It was hard times after the war, so he must had powerful feelings for my daddy to spend that kind of money. Daddy wouldn't never tell me what he really thought of Master Grimm, so that's a secret he took to the grave. I got treated good because I was my daddy's son, but I wasn't sad when Master Grimm passed.

After Emancipation, they open up the Penn School for teaching the old slaves to read and write, but my mama didn't make us kids go because she teach us. She had stories pass down to her from oldest times, when the first come over the sea. My daddy's line the oldest at Eastwater, go back five generations to a slave boy name Gus. My daddy made me memorize our line all the way back, and I knows it still. My daddy was Festus, who was the son of Maum Ellie, who was the daughter of George, who was the father of Ceasar, who was the son of Berty, who was the daughter of Gus, who come to Charleston and got bought by the first Master Grimm. I teach it to my kids, but they don't wanna remember it. Just like my brother.

See, my folks, they knew the words those old slaves say and the songs they sing. But my brother, he didn't want none of that. He said we all need to go North and get civilized, but my mama say she never leave Eastwater because to see the ocean was to see the bridge from here to there and we be lost if we let it go out of sight. My brother go to find a job up North. His name was Sugar because my mama say he was the sweetest baby ever live.

I drove the carriage when Master and Missus went out, so I got to see a little of the world that way. One time, they go to Charlotte to visit some friends and had me drive them. Got to stay a whole week. While we was there the circus come to town and we go down to see it. I was sitting there in the colored section when I seen the elephants come out, and sitting on top of one is my brother Sugar, but I don't hardly recognize him because he got paint stripes on his face. He was wearing leather britches and a necklace of bones and was shaking some kind of stick at folks, looking mean and yelling some talk I never heard. The circus man say they found him naked in the African jungle living with a bunch of gorillas. All the white people looked real scared, one little white boy was crying, but all the colored folks was laughing and pointing at my brother and saying, "What kind of fool is that?" I didn't know what to do. Sugar hadn't wrote us much since he left except to say he was working and not to worry. Sitting there watching him, I know why he don't write more. He was shamed, and so was I, so I didn't let him see me. On the way home, Master Grimm asked me, "Wasn't that jungle boy your brother that run off North?" and I said, "No sir, it wasn't him."

A long time ago. After that, we stopped hearing from Sugar. My folks died, and when I got my own family, I just never told them about my brother. Didn't seem much point. Fact, I ain't never told nobody this story but you.

âor

Boy Meets Girl,

Boy Marries Girl,

The End

IN

1967, Hoosier sportswriters agreed on one thing: Ethan Perdido of Lima, Indiana, was the best baseball player in the state. The sports editor for the

Lima Journal

penned an editorial on Ethan's behalf: "Indiana has a Mr. Basketball. Why not a Mr. Baseball?" It didn't happen, but this revolutionary idea did bear some fruit: Ethan received a full scholarship to play ball at Purdue University. In an interview, Ethan thanked God, his parents, his coaches, and his girlfriend for believing in him. The reporter gleefully noted that Ethan's teammates had dubbed him "The Undertaker," not only for his prowess on the field, but also because he was heir to Lima's oldest mortuary, the Perdido Funeral Home. "I love baseball," Ethan said in the article, "but I'll probably wind up back in Lima eventually to take over the family business."

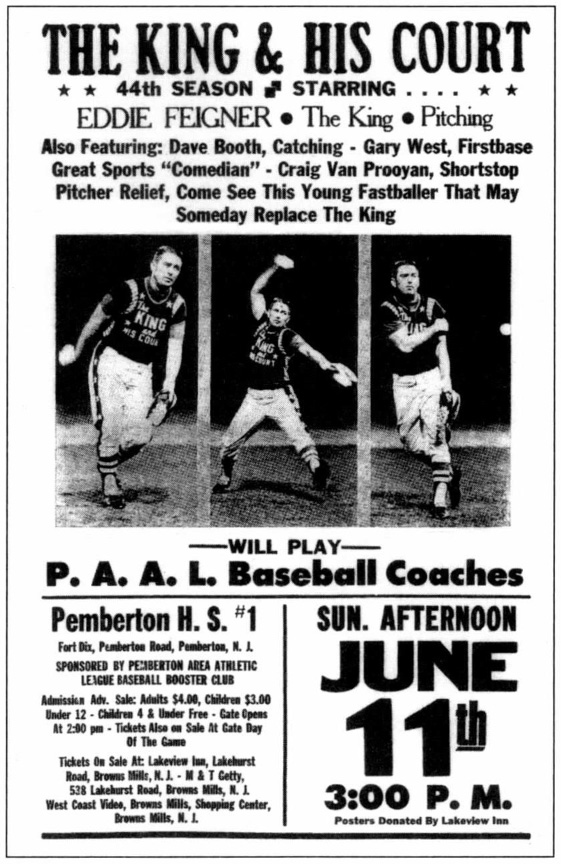

To keep himself in shape the summer before he started school, Ethan joined a fast-pitch softball league and played first base for the B&B Grocery Roustabouts. He thought the transition would be easy, since the ball was bigger. Quickly, Ethan discovered fast-pitch was tougher than it looked. The distance from home plate to the pitcher's mound was much shorter, for one thing, which threw off his hitting, and since the ball moved differently, his fielding suffered. But by July, Ethan had his game back, just in time for a match up between the Roustabouts and the King and His Court, the Harlem Globetrotters of fast-pitch softball.

The King and His Court was born on an afternoon in 1946. A gifted pitcher named Eddie Feigner threw a 33â0 shutout. When the disgruntled losers taunted him, Eddie claimed he could whip them again with just a catcher. "But you'd probably just walk us both," he mocked, "and then where'd we be?" So he drafted a first baseman and a shortstop and the four-man team still won, 7â0. Eddie declared himself "The King" and took his court on the road like a barnstorming softball circus. The King's fast ball came in at over 100 miles an hour, his curve dropped like an elevator, and he had trick pitches, too: blindfolded, behind the back, between the legs. He threw strikes from second base. His troupe traveled from town to town, taking on all comers. Most nights, the King and His Court went home victorious, and at three bucks a head, a lot richer as well.

But this story isn't about the King and His Court. It's not about the difference between baseball and the dying tradition of men's fast-pitch softball. It's not about Ethan Perdido and his

It's a Wonderful Life

-ish choice between duty to family and personal dreams. This story is about the girl sitting on a wooden-bleacher throne: Ethan's girlfriend, Laura Hofstadter.

Laura attended every game her boyfriend played, but not because she especially loved baseball. She went because it was something to do, and because she loved Ethan, or thought she did. She liked it when people looked at her when Ethan got a hit or made a great play. It made her feel like somebody. The summer he played for the Roustabouts, she became a temporary member of the Softball Wives, the husband-cheering women who dotted the stands of Winnesaw Park. The Softball Wives didn't care much for Laura. They thought her standoffish, and they resented the way their husbands stared at the browned belly revealed by her knotted shirts. Laura felt the resentment in their smiles and polite waves, but when Ethan asked her why she wouldn't sit with the other women, she couldn't find the words to explain.

But the night that the King and His Court played the Roustabouts, Laura was forced to join the Softball Wives in the bleachers. The game had brought out half the town, after all. That day's edition of the

Lima Journal

claimed Eddie Feigner was the most underrated athlete of his time. Earlier that month, in an exhibition game with major-league all-stars, Eddie had struck out Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Brooks Robinson, Maury Wills, Harmon Killebrew, and Roberto Clemente. In a row. K-K-K-K-K-K.

The stands were packed with sweating bodies. Laura tried hard to keep herself contained, but she couldn't help but touch the women on either side of her, couldn't help but wonder how many years away she was from becoming them. Betty Pollard, who worked down at the Lima Savings Bank with her, had thighs that spread like dough, and Carol Winters bore a whole river system of varicose veins on her legs. Both women had children, two or three each, although Laura could never count them because they were always racing around chasing foul balls.

The two teams were finishing their warm-up. The King and His Court played catch, two pills slapping leather mitts, one exclamation mark after the other, punctuating the night. Ethan stood at home plate, hitting balls to his teammates. Laura didn't care much for baseball, but she loved its sounds, the notes Ethan played on his bat; the long flies for the outfielders hit the bat's sweet spot with a deep, woody thwack, and the skittering ground balls he hammered out for the infielders cracked like gunshots. She liked baseball because you could feel it humming inside you every time something good happened.

A woman with a bad vibrato sang "The Star-Spangled Banner," and then the King got on the P.A. Laura saw him up in the scorekeeper's box, a stocky man with a flattop and a big grin.

"LADIES AND GENTLEMAN, I'M EDDIE FEIGNER, AND WELCOME TO TONIGHT'S GAME BETWEEN THE B&B GROCERY ROUSTABOUTS..."