The Circus in Winter (30 page)

Read The Circus in Winter Online

Authors: Cathy Day

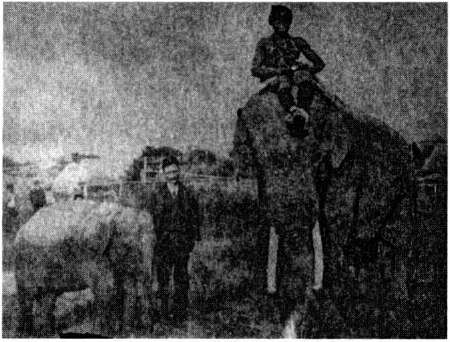

This is a picture of my great-great-uncle, Henry Hoffman, and his bull elephant Charlieâcirca the late 1880s or early 1890s. If you look closely, you can see Hoffman is carrying a "bullhook" in his right hand, a metal rod with blunted prongs which elephant handlers use to poke, prod, and train their pachyderms. In April of 1901, Hoffman took Charlie and the other elephants for their daily bath in the Mississinewa, the river that ran alongside the winter quarters complex outside my hometown of Peru, Indiana. For reasons that remain unclear, Charlie killed my great-great-uncle that dayâgrabbing him off a pier, throwing him high in the air, and then holding him underwater with his trunk and front feet. During this struggle in which Hoffman fought (unsuccessfully) for his life, Charlie bent the metal bullhook. He had to be "put down" after this incident, which I describe fictionally in the story "The Last Member of the Boela Tribe."At the time of this tragedy, Hoffman's son Fred was just a year old; the circus employees gave Fred and his mother the bent bullhookâas a memento, I guess. Fred Hoffman eventually married my maternal grandmother's sister, Margaret. When I visited their home as a child, I noticed this strange metal object propped up against the wall beside Uncle Fred's LazyBoy chair, but I didn't realize what it was until many years later when I began doing the research for

The Circus in Winter.

Fred died in 1997, and Aunt Margie had to sell their house. She asked me if there was anything from the house I wanted for myself, and I didn't hesitate to ask for the bullhook. She said, "Wouldn't you rather have my silverware or a nice pair of earrings?" I politely declined.

This photograph of the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus sideshow was taken by Edward J. Kelty. Known as a "banquet photographer," Kelty made his living taking large, 12Ã20 group pictures at conventions and meetings, but during the 1920s and 1930s, he sidelined as a circus photographer. (Check out a collection of these in

Step Right This Way: The Photographs of Edward J. Kelty,

published in 2002.) I found this particular picture in 1991 in a circus history bookâthe editors gave it a two-page spread, so the names and faces in the picture jumped off the page. My first thought was, "My God, all these people in the picture probably lived in my hometown during the winter!" My eye was particularly drawn to the three black men in grass skirts standing in the left-hand corner of the picture, who are most likely "The Boela Tribe of African Pinheads" advertised on the sideshow banner behind them.

Who were those men?

I wondered, and began creating a life for them in my imagination. This is how the story "The Last Member of the Boela Tribe" began, and I worked on itâoff and onâfor a decade. During those years, I did research on freaks (the real and the fake), pinheads, and minstrelsy. Sociologically speaking, the American circus reflected the society it sought to entertain. Like the old minstrel shows, the circus was a form of popular entertainment where America's troublesome (and often disturbing) racial and ethnic attitudes played themselves out in the center ring and on the side-show stage. I discovered so much interesting material, and I feared I'd never be able to fit it all into one story, but somehow I managed to do it. I also saw the name "Jennie Dixianna, America's Doll Lady" on the right-hand banner. I loved the name and decided to use it for my femme fatale acrobat. The "real" Jennie Dixianna is most likely the female midget standing first row center, next to the Fat Lady.

Jennie Dixianna's character is based on 1920s aerialist/star Lillian Leitzel. Her famous act, "The One-Armed Plange," involved repeated turns on a hanging swivel and loop, revolutions which required her to dislocate her shoulder with each turn. Amazed by this feat, I created Jennie Dixianna's "Spin of Death." Whenever I see this photograph, part of me knows that it is a picture of a real woman, but another part of me thinks of it as a photograph of my Jennie Dixianna performing her spin of death.

The skull of the elephant that killed my great-great-uncle sits in the Miami County Museum. Never, not once, while growing up in Peru, Indiana, did this strike me as odd or fascinating. After all, lots of people in Peru had ties to the circus; the descendants of cat trainer Clyde Beatty and "Weary Willie" clown Emmett Kelly still live there. In college, when people asked me, "Where are you from?," I told them, "Oh, this little town called Peru" and mentioned the skull off-handedly. Many didn't believe me. When it came time to write my undergraduate thesis in creative writing, my teacher said, "You're from that weird circus town, right? Why don't you write about that?" I dismissed the idea at first, saying Peru was too boring to write about, but he insisted. So in 1991, I went back for the first of many research trips. At the museum, the curator informed me that the skull on display was not really Charlie's skull, but rather the skull of a smaller, female elephant they'd purchased from the Indianapolis Zoo. However, the tusks, she said, were the real deal. Working under the assumption that the skull was a fake, I incorporated that tidbit into "The Last Member," only to discover recently that the curator had misspoken; it

is

Charlie's skull, but the tusks are not. Luckily, by this time, the "truth" didn't matter that much anymore.

I found this photograph during my first research trip to Peru in 1991. It was taken at the Hagenbeck-Wallace winter quarters in 1913 after a horrible flood devastated most of the town; the circus complex, situated right on the banks of the swollen Mississinewa River, was hit incredibly hard. In a newspaper account, I read that many of the circus animals died from drowning or exposure to the cold water. Some of the elephants, such as the one above, failed to head for higher ground because they were accustomed to going to humans when trouble arose. The elephants wailed outside the windows of their keepers, who tried to keep the animals alive by feeding them hay out the windows, but eventually, the pachyderms succumbed to the bitter cold water. (Why this particular man decided to perch himself on top of the dead elephant, I'll never know...) I also remembered another story from my family's oral history; my maternal grandmother's parents lived in the town of Peru and were trapped (along with an infant) on the second floor of their home for days until they were rescued. When I started writing the story "Winnesaw," I had this picture in my head, along with the imagined memory of my long-dead relatives struggling to survive. I decided to move my "family story" and the characters (Grace and Charles and Mildred) from town to the country, so that they could bear witness to the devastation caused by the Flood of 1913.

Before Will Rogers and Gene Autry, there was Tom Mix, the original American Cowboy. Mix parlayed his silent-film stardom into big-top success, headlining the Sells-Floto Circus from 1929â1932 at a reported $10,000 a week. This picture was taken during those years, when Tom Mix and his Wonder Horse, Tony, called Peru their winter home. I think every older gentleman in Peru can tell you the same story from his boyhoodâworking up the courage to shake Tom Mix's hand. I don't know where Tony stayed, but Mix lived downtown at the Bearss Hotel, where (it is reported) he shot out chandelier lights and wooed local ladies when he grew bored. For the record, Tom Mix didn't keep a tally of his conquests (not that I know of anyway), and he died in a tragic car crash, not from swallowing a toothpick (that was the fate of one of my heroes, Sherwood Anderson, author of

Wines burg, Ohio).

When I told my maternal grandmother that I wanted to write a book about the circus in Peru, she began sending me files of old newspaper clippings and photographs, including this one. On the back of the photo, someone had written: "Hoffman, Ding Dong, Charlie, and his Jungle Goolah BoyâIowa, 1900." For a long time, I figured that Jungle Goolah Boy was just some silly-sounding "African" name the circus owners had come up with. In 1998, I got a research grant to travel to Baraboo, WI (hometown of the Ringling Brothers) to do research in the Robert L. Parkinson Library and Research Center at the Circus World Museum. I showed the above photograph to the curator, who said they had no record of a Jungle Goolah Boy or who the man in the photo might have been. A year later, I was reading Edward Ball's book

Slaves in the Family

and came across the term "Gullah," descendents of slaves who worked the rice plantations in South Carolina and Georgia. Unlike most slaves, the Gullah managed to retain a great deal of their African language and customs through the generations. Finally, I realized that "Goolah" was probably someone's mispronunciation or misspelling of "Gullah." What I admired about

Slaves in the Family

was Ball's willingness to disclose the contents of his slave-holding family's ledgers and correspondence; through diligent sleuthing, he helped many African-American families find their roots, a lineage that for many is impossible to find. I wished that I could find a similar "paper trail" for my Jungle Goolah Boy, and so I decided to create one for him. This is why the story "Jungle Goolah Boy" is told entirely in documents. For verisimilitude, I studied a lot of old documents, trying to mimic vocabulary, presentation, and tone.