The Classical World (3 page)

Read The Classical World Online

Authors: Robin Lane Fox

Like justice and freedom, luxury was a term with a very flexible history. Where exactly does luxury begin? According to the novelist Edith Wharton, luxury is the acquisition of something which one does not need, but where do ‘needs’ end? For the fashion-designer Coco Chanel, luxury was a more positive value, whose opposite, she used to say, is not poverty, but vulgarity; in her view, ‘luxury is not showy’. Certainly, it invites double standards. Throughout history, from

Homer to Hadrian, laws were passed to limit it and thinkers saw it as soft or corrupting or even as socially subversive. But the range of luxury and the demands for it went on multiplying despite the voices attacking it. Around luxury we can write a history of cultural change, enhanced by archaeology which gives us proofs of its extent, whether the bits of blue lapis lazuli imported in the pre-Homeric world (by origin, all from north-east Afghanistan) or rubies in the Near East imported after Alexander (they are shown, by analysis, to have come ultimately from unknown Burma).

By the time of the classicizing Hadrian, the political freedoms of the past classical age had diminished. Justice, to our eyes, had become much less fair, but luxuries, from foods to furnishings, had proliferated. How did these changes occur and how, if at all, do they interrelate? Their setting had been intensely political, as the context of power and political rights changed tumultuously across the generations, to a degree which sets this era apart from the centuries of monarchy or oligarchy in so much subsequent history. If this era is studied thematically, through chapters on ‘sex’ or ‘armies’ or ‘the city-state’, it is reduced to a false, static unity and ‘culture’ is detached from its formative context, the contested, changing relations of power. So this history follows the threads of a changing story, within which its three main themes have a changing resonance. Sometimes it is a history of great decisions, taken by (male) individuals but always in a setting of thousands of individual lives. Some of these lives, off the ‘grand narrative’, are known to us from words which people inscribed on durable materials, the lives of victorious athletes or fond owners of named racehorses, the lady in Alexander the Great’s home town who had a curse written out against her hoped-for lover and his preferred Thetima (‘may he marry nobody except me’), or the sad owner of a piglet which had trotted by his chariot all the way down the road to Thessalonica, only to be run over at Edessa and killed in an accident at the crossroads.

14

Scores of these individuals surface yearly in newly studied Greek and Latin inscriptions whose surviving fragments stretch scholars’ skills, but whose contents enhance the diversity of the ancient world. From Homer to Hadrian, our knowledge of the classical world is not standing still, and this book is an attempt to follow its highways as Hadrian, its great global traveller, never did.

The Archaic Greek World

In Mainland Greece, the Archaic Age was a time of extreme personal insecurity. The tiny overpopulated states were just beginning to struggle up out of the misery and impoverishment left behind by the Dorian invasions when fresh trouble arose: whole classes were ruined by the great economic crisis of the seventh century, and this in turn was followed by the great political conflicts of the sixth, which translated the economic crisis into terms of murderous class warfare… Nor is it accidental that in this age the doom overhanging the rich and powerful becomes so popular a theme with the poets

…

E. R. Dodds,

The Greeks and the Irrational

(1951), 54–5

The close personal association of the upper classes at this time was a tremendous force in promoting the lightning swiftness of contemporary change; in intellectual outlook the upper classes seem scarcely to have boggled at any novelty. With remarkable openness of mind and lack of prejudice they supported the cultural expansion which underlay classical achievements and much of later western civilization. Great masses of superstition and magic trailed down into historic times from the primitive Dark Ages… That past, as exemplified in the epics, was not dismissed in its most fundamental aspects, but writers, artists and thinkers felt free to explore and enlarge their horizons. The proximate cause, without doubt, was the aristocratic domination of life.

Chester G. Starr,

The Economic and Social Growth

of Early Greece, 800–500

BC

(1977), 144

Homeric Epic

So Priam spoke, and he roused in Achilles the desire to lament his father: Achilles took his hand, and pushed the old man gently away. And the two of them remembered: one wept aloud for Hector slayer of men, crouched before the feet of Achilles, but Achilles wept for his own father and then, too, for Patroclus

… Homer,

Iliad

24.507–11

Travelling in Greece, Hadrian stopped at its most famous oracle, Delphi, in the year

AD

125, and asked its god the most difficult question: where was Homer born and who were his parents? The ancients themselves would say, ‘let us begin from Homer’, and there are excellent reasons why a history of the classical world should begin with him too.

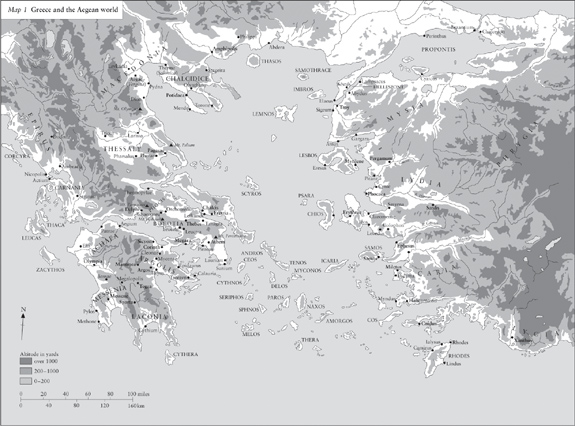

It is not that Homer belongs at the ‘dawn’ of the Greeks’ presence in Greece or at the beginnings of the Greek language. But for us, he is a beginning because his two great epics, the

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

, are the first long texts in Greek which survive. During the eighth century

BC

(when most scholars date his life), we have our first evidence of the use of the Greek alphabet, the convenient system of writing in which his epic poems were preserved. The earliest example at present is dated to the 770s

BC

and, with small variations, this alphabet is still being used for writing modern Greek. Before Homer, much had happened in Greece and the Aegean, but for the previous four centuries nothing had been written down (except, in a small way, on Cyprus). Archaeology is our one source of knowledge about this period, a ‘dark age’ to us, though it was not ‘dark’ to those who lived

in it. Archaeologists have greatly advanced what we know about it, but literacy, based on the alphabet, gives historians a new range of evidence.

Nonetheless, Homer’s poems were not histories and were not about his own times. They are about mythical heroes and their doings in and after the Trojan War which the Greeks were represented as fighting in Asia. There had certainly been a great city of Troy (‘Ilion’) and perhaps there really had been some such war, but Homer’s Hector, Achilles and Odysseus are not historical persons. For historians, the value in these great poems is rather different: they show knowledge of a real world, their springboard from which to imagine the grander epic world of legend, and they are evidence of values which are implied as well as stated. They make us think about the values of their first Greek audiences, wherever and whoever they may have been. They also lead us on into the values and mentalities of so many people afterwards in what becomes our ‘classical’ world. For the two Homeric poems, the

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

, remained the supreme masterpieces. They were admired from their author’s own era to Hadrian’s and on to the end of antiquity, without interruption. The

Iliad

’s stories of the Trojan War, the anger of Achilles, his love for Patroclus (not openly said to be sexual) and the death of Hector are still among the most famous myths in the world, while the

Odyssey

’s tales of Odysseus’ homecoming, his wife Penelope, the Cyclops, Circe and the Sirens are a lasting part of many people’s early years. The

Iliad

culminates in a great moment of shared human loss and sorrow in the meeting of Achilles and old Priam whose son he has killed. The

Odyssey

is the first known representation of nostalgia, through Odysseus’ longing to return home. Near its end it too brings us an encounter with pitiable old age when Odysseus comes back to his aged father Laertes, tenaciously at work among his orchard of trees, and unwilling to believe that his son is still alive.

The poems describe a world of heroes who are ‘not as mortal men nowadays’. Unlike Greeks in Homer’s own age, Homer’s heroes wear fabulous armour, keep open company with gods in human form, use weapons of bronze (not iron, like Homer’s contemporaries) and drive in chariots to battle, where they then fight on foot. When Homer describes a town, he includes a palace and a temple together, although

they never coexisted in the world of the poet and his audience. He and his hearers certainly did not take his epic ‘world’ as essentially their own, but slightly grander. Nonetheless, its social customs and settings, particularly those in the

Odyssey

, seem to be too coherent to be the hazy invention of one poet only. An underlying reality has been upheld by comparing the poems’ ‘world’ with more recent pre-literate societies, whether in pre-Islamic Arabia or in tribal life in Nuristan in north-east Afghanistan. There are similarities of practice, but such global comparisons are hard to control, and the more convincing method is to argue for the epics’ use of reality by comparing aspects of them with Greek contexts after Homer. The comparisons here are plentiful, from customs of gift-giving which are still prominent in Herodotus’ histories (

c.

430

BC

) to patterns of prayer or offerings to the gods which persist in Greek religious practice throughout its history or the values and ideals which shape the Greek tragic dramas composed in fifth-century Athens. As a result, to read Homer is not only to be swept away by pathos and eloquence, irony and nobility: it is to enter into a social and ethical world which was known to major Greek figures after him, whether the poet Sophocles or that great lover of Homer, Alexander the Great. In classical Athens in the late fifth century

BC

, the rich and politically conservative general Nicias obliged his son to learn the Homeric epics off by heart. No doubt he was one of several such learners in his social class: the heroes’ noble disdain for the masses would not have been lost on such young men.

Homer, then, remained important in the classical world which came after him. Nonetheless, the Emperor Hadrian is said to have preferred an obscure scholarly poet, Antimachus (

c.

400

BC

), who wrote on Homer’s life. By beginning with Homer we can correct Hadrian’s perversity; what we cannot do is answer his question about Homer’s origins.

If the god at Delphi knew the answer, his prophets were certainly not giving it away. All over the Greek world, cities claimed to be the poet’s birthplace, but we know nothing about his life. His epics, the

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

, were composed in an artificial, poetic dialect which suited their complex metre, the hexameter. The poems’ language is rooted in the dialects known as ‘east Greek’, but a poet could have learned it anywhere: it was a professional aid for hexameter-poets, not

an everyday sort of spoken Greek. It is more suggestive that when the

Iliad

uses everyday similes, it does sometimes refer to specific places or comparisons in the ‘east Greek’ world on the western coastline of Asia. These comparisons needed to be familiar to their audience. Perhaps the poet and his first audiences really did live there (in modern Turkey) or on a nearby island. Traditions connected Homer, in due course, with the island of Chios, a part of whose coastline is well described in the

Iliad

. Other traditions connected him strongly with Smyrna (modern

İ

zmir) across from Chios on the Asian mainland.

Homer’s dates have been equally disputed. Many centuries later, when Greeks tried to date him, they put him at points which equate to our dates between

c.

1200 and

c.

800

BC

. These dates were much too early, but we have come to know, as their Greek proponents could not, that the Homeric poems did refer back to even older sites and palaces with a history before 1200

BC

. They describe ancient Troy and they refer to precise places on the island of Crete: they allude to a royal world at Mycenae or Argos in Greece, the seat of King Agamemnon. The

Iliad

gives a long and detailed ‘catalogue’ of the Greek towns which sent troops to Troy; it begins around Thebes in central Greece and includes several place-names unknown in the classical world. Archaeologists have recovered the remains of big palaces at Troy (where recent excavations are enlarging our ideas of the site’s extent), on Crete and at Mycenae. Recently they have found hundreds of written tablets at Thebes too. We can date these palaces way back into a ‘Minoan’ age (

c.

2000–1200

BC

) in Crete and ‘Mycenaean’ palace-age in Greece (

c.

1450–

c.

1200

BC

). In fact, Thebes, not Mycenae, may now turn out to have been at the centre of it.

1

In this ‘Mycenaean’ age Greek was being quite widely spoken and written in a syllabic script by scribes who worked in the palaces. In this period Greeks were also travelling across to Asia, but not, as far as we know, in one major military expedition. Thanks to archaeology, we are now aware of a long-lost age of splendour, but it was not an age which Homer knew in any detail. The

Iliad

’s ‘catalogue’ is the one exception. Even so, he only had oral stories and after five hundred years they had retained none of the social realities. A few Mycenaean details about places and objects were embedded in poetic phrases which he had inherited from illiterate predecessors.

The formative years for his main heroic stories were probably

c.

1050–850

BC

, when literacy had been lost and no new Greek alphabet existed. As for the social world of his poems, it is based on an age closer to his own time (

c.

800–750

BC

): the ‘world’ of his epics is quite different from anything which the archaeology and scribal writing of the remote ‘Mycenaean’ palaces suggest.