The Clay Dreaming (32 page)

Authors: Ed Hillyer

‘Clewley, an’ his sort,’ muttered Tubridy, ‘oh, they appear awl friendly-loike, but they’ll turn you in an instant if they sees their chance. That they will!’

Squeezing into Station-place, he all but ran her up the steps to the platform.

‘An onnatural instink stews in their hearts,’ he said. ‘For vengeance! An’ once they think themselves wronged, they niver forget. Niver!’

Only once they had reached the top step did he relax hold of her. He forced a little kindness again to show in his face.

‘Thank you…’ Sarah struggled to catch her breath. ‘Thank you again, sergeant,’ she said, ‘for escorting me today.’

Tubridy bowed and tipped his helmet, ever the gentleman. ‘Always a pleasure, miss, escortin’ a lady to church…or ony other house o’ worship!’ His damp red whiskers curled into a devilish smile. ‘And in a heathen city such as this?’ he said. ‘Why, oi was only doin’ m’ duty!’

As he trotted away down the steps, Tubridy again began to sing.

‘Saint Patrick was a gentleman and came of decent people,

He built a church in Dublin town, and on it put a steeple…’

A shrill whistle drowned out the rest of his verse. A train was about to pull into the station. Sarah was torn, whether to run onto the platform before he was properly out of sight, or wait and watch his departure. An icy claw raked her insides: after all he had done for her, all their time together, she had never thought to let him know her name.

‘…’Twas on the top of Dublin’s hill Saint Patrick preach’d his sermon,

That drove the frogs into the bogs, and banished all the vermin!’

Already out of sight, she yet heard his fine, true voice and took it as a comfort, before a gush of steam and a clatter of doors swallowed her up, and it, too, was gone.

The train journey from Shadwell Station into Fenchurch-street took only minutes. Sarah sat and stared out of the window. The low black housing, sweeping by, merged with her blank reflection. A lock of her hair had fallen loose and she curled it in her long fingers. Seeing again the fear in Tubridy’s eyes, she finally appreciated what appalling risks she had taken; yet, feeling the heat of blood in her cheeks, she also thrilled to it.

The crowding walls abruptly fell away, to disclose a broad cityscape.

Soon enough, Sarah discovered the omnibus route for her journey home. She sat on board, much as she had on the train, in a daze.

The bus was bypassing the vast cathedral. Affairs seemed to circle St Paul continually, as moths did a flame.

The son of a Jew, the man Saul had been both blasphemer and persecutor, long before being recast St Paul, ‘Apostle of the Gentiles’, and one of God’s principal proponents. But then by equal token, Lucifer, Bringer of Light, had been an angel of the Lord, and ended up no less than Satan, the Devil Incarnate. The traffic, so it seemed, might flow in either direction.

Sarah leant forward in her seat, the better to admire the great dome.

She looked up into an emptiness of sky, and had to raise a hand to shield her eyes from the glare. Her thoughts ran swift as lightning, to Joseph Druce, the wicked wretch, and his revelation in the wilderness; his lawless heart, lost in grief; his fugitive soul, drowned with fear; and then a mile of geese, the sun reflected on their down, temporarily blinding him.

The rim of the dome, lit from beyond the encircling clouds, deflected the subtle rays of early evening sun: she saw the head and shoulders of a colossus reduced to mere outline, the imposing mass an empty shadow, little more than a dream.

The sight of St Paul’s Cathedral should have revived a good Christian. Instead, from this extreme angle, the entire fabric appeared to shift on its foundations, almost as if it might topple at any instant.

Anything might yet be possible, anything at all.

Sarah recrossed her own threshold with a profound rush of relief.

At some point during the day, her father had suffered a seizure and soiled himself. With Mary no longer present, nor herself in attendance, there had been no one to come to his aid. Heaven only knew how long he had lain enfeebled, and in an appalling state.

Lambert Larkin was mortified, beside himself with shame. He ran a slight fever, moaning and mumbling unintelligible nonsense as Sarah cleaned him and changed the bedding. The mattress was damp but she could not move him, not by herself, and neither did she think it in his best interest. A few layers of extra bedding would have to serve as a barrier. Once he was made comfortable again, she ran downstairs, hoping to find Dr Epps still in his surgery. The house was empty, the doctor gone for the day, as well as his staff. She would have run direct to his home in Hanover-square, or arranged for a message to be sent, but not at risk of leaving her poor father alone again.

Sarah fetched some coal and set a fire in his room. She made him soup, and helped him to eat. Little was said, and at length his mind seemed calmed. He looked up at her with such pathetic gratitude that it drove a lance through her heart. Not long after, thank the Lord, he drifted into sleep; Sarah did not leave his side, even for some hours after that. She simply could not forgive herself.

One floor below, Brippoki sits in darkness. Window and curtains gape open. The glowbug lamps in the street light up the ceiling for a time, until they are extinguished. Following his latest bout with London life, Thara’s front parlour seems ever more an oasis of calm and serenity. At long last, he is able to relax.

The old man clock in the hallway chimes the hours. It is past midnight before a familiar shadow darkens the doorway. Guardian. Drawn with cares, she wears that same exhausted look he is all too used to seeing on the infinite faces that the city presents.

Brippoki speaks softly, so as not to alarm her.

‘Thara,’ he says.

To see her makes his liver glad.

‘

Nei

-Thara.

Ba-been!

’

‘Bri…Brippoki?’ whispered Sarah. ‘Oh, there you are. Hold on a moment while I…’

Rather than light the gasolier in the centre of the room, or even the paraffin table-lamp, she returned with a solitary candle.

The Aborigine was no more than a silhouette. Sarah drew closer. She immediately noticed a further change in his appearance, mistaking it a moment for an effect of candlelight. His features had always seemed fleshy: but then she gasped, almost inhaling the flame. Brippoki’s face looked to have been smacked with a shovel.

‘What,’ she said, ‘what’s

happened

to you?’

Her terrible guilt forgotten, she ran to get water and a clean towel.

Bruises did not show on his black skin, but she could tell where it was puffy and swollen. There were visible cuts to his cheek, and brow, and lips. She

bathed them, making sure they were clean, but there seemed no point applying bandages; she would have had to wrap his entire head, like an Egyptian mummy.

‘Are you hurt anywhere else?’ she asked.

Stiff movements and grimaces showed that his sides ached, but Brippoki impatiently waved her away. ‘Him nutten,’ he declared.

Sarah stood back a pace, feeling useless. He sat in his rags, looking completely worn out. The contrast from when he had first fetched up on her doorstep was sad, and she had thought him weary and dishevelled even then. That very first time she had seen him – at Went House, Town Malling – he had attracted her attention by being quieter than his compatriots: shy and retiring, like herself, the lines of his face drawn deep.

They yawned deeper still. That air of unknowable tragedy always lurking behind his eyes seemed almost nakedly revealed.

For a period they sat, saying nothing. At length, Sarah picked up her notebook, more for distraction from their separate woes than anything else.

‘A lot has happened, since last we saw each other,’ she said.

She opened up the book.

‘I myself,’ she said, ‘have not been idle. I found something out today that I think you may find intriguing… George Bruce.’

She suddenly had Brippoki’s complete attention.

‘The name never seemed to mean much to you. Nor any of the others I have mentioned. Only the man. How about…’ she flourished a piece of paper ‘…Joseph Druce?’

Brippoki looked a little wary, but did not otherwise react.

‘

Josiah

Druce?’

No.

Sarah grew a little impatient. Getting to the bottom of the mystery man’s identity, she had thought that she might at last be getting somewhere.

‘I received a letter this morning from the Admiralty in London,’ she said, ‘presenting me with certain evidence, evidence that corroborates a suspicion held for some time now.’

Brippoki looked confused.

‘You bin dancing?’ he said, his tone disbelieving.

‘I…eh? No.’ Sarah barely masked her annoyance. She strove to measure her words. ‘I have been to look in the…in a very special book,’ she said. ‘A sacred book.’

Guruwari

.

‘

Uah

,’ he nodded. ‘You Guardian!’

She followed his train of thought. ‘Not in the library,’ said Sarah. ‘I was in a church. I went to that place where the man calling himself George Bruce has

told us he was born. I went to the church there, where he was blessed and given his name. His true name.’

Brippoki raised his hands. They were cupped, as if he meant to clap them over the flickering flame of the candle. The deep shadows that filled the room behind him jerked crazily; as, she supposed, they did behind her.

‘George Bruce,’ she said, ‘is a fiction, a phantom. He is an invention.’

She checked to see that he followed, that Brippoki understood.

‘He isn’t real,’ she said. ‘He never existed. At least, not by that name…’

She belaboured the point, wanting him sure of it.

‘His real name was Joseph Druce.’

Brippoki’s lips shaped themselves as if he were about to repeat it.

‘George Bruce and Joseph Druce,’ emphasised Sarah. ‘Two different names. One and the same man.’

Brippoki clapped his hands over both ears.

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘it’s true. I have it written here. Exactly as it is written in the sacred book.’

Brippoki’s eyes opened wider. They were huge bloodshot orbs. He looked truly disturbed. Sarah almost wished she could take the words back, but she had come too far to stop short.

‘“July 6, 1777, Joseph and Josiah, twin sons of John Druce, Distiller, and Mary…”’

‘

WA-DAY!

’

She got no further. Brippoki flinched and fell to an awful trembling, then suddenly arose, shrieking. His limbs struck out in every direction as he stumbled from one piece of upset furniture to the next. The candle was blown out.

Sarah stood, speechless, hearing a voice, but seeing no man.

‘

WA-day,

’ he cried out in the darkness. ‘

Wa-daaayyy!

’

With another crash and a bang he made the open window, and in an instant was gone.

‘BRIPPOKI!’

Sarah heard a wail from upstairs. All of the great commotion had woken her father.

‘Who?’ he hooted. ‘Who is here?’ The pallor of his face, dark around the eyes and open mouth…his head shone like a skull in the blackness.

Sarah brought the candle forward. ‘It’s all right,’ she said. ‘I’m here.’

‘Frances?’

‘Sarah.’

‘Who else?’ demanded Lambert. ‘Who else is here?’

Sarah could not tell if he shivered from cold, fever, or fear. He had kicked off the main part of the coverlet, and was clad only in a thin sheet. It wound around his sweat-damp limbs and clung to him like a cerement, the shape

beneath defined by its shallows and protuberances. She retrieved the blankets from the floor, and tucked them in around him.

‘No one,’ she said. ‘There is no one else here. Only me, Sarah.’

‘I heard a noise,’ he said. ‘An awful cry.’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I’m sorry. That was me. I knocked over a table in the parlour. I was clumsy and the lamps were out.’

She couldn’t bear lying to him.

‘There was a voice,’ he insisted. ‘It didn’t sound like your voice…’

‘Hush, don’t think of it,’ she said. ‘Don’t worry yourself. Try to get some sleep.’

‘Such a terror in the sound…’ he said.

‘

Hushhht

.’

‘…such terror…’

Wednesday the 10th of June, 1868

‘There was a Door to which I found no Key:

There was a Veil past which I could not see:

Some little Talk awhile of ME and THEE

There seemed – and then no more of THEE and ME.’

~

Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám

‘I should not like a son of mine to be born and bred in Ratcliffe-highway. That there would be a charming independence in his character, a cosmopolitanism rich and racy in the extreme, a spurning of that dreary conventionalism which makes cowards of us all, and under the deadly weight of which the heart of this great old England seems becoming daily more sick and sad – all this I admit I should have every reason to expect, but, at the same time, I believe the disadvantages would preponderate vastly.’

Sarah Larkin laid down the book she was re-reading. She drew her shawl a little tighter about her shoulders. Out of the open window the night sky seemed less obscured by cloud than of late; the moon looked more than usually far away.

From the hallway, the grandfather clock sounded quarter-to. The hour would soon be ten, and for the second night in a row there had been no sign of Brippoki.

Her father having taken badly in her absence, Sarah had not dared leave the house since. Had she not been away to Ratcliff she would anyway have been in the library, but still, she could not forgive herself.

Tuesday morning first thing, Dr Epps had graciously paid a house call. Having only to climb two flights of stairs, he had charged for it nonetheless. She would have paid any price if only to gain peace of mind, and speed her father’s recovery.

The doctor had assured her Lambert would recover in good time. She should turn his body frequently in the bed, so as to avoid his getting sores. Nothing much else could be done, except to administer sleeping draughts and

let him rest. And so Sarah sat and maintained her lonely vigil: by day at her father’s bedside, and every night at the open window one flight below.

She pluck’d a hollow reed.

As for her task at the Reading-room, she remained a little ahead of the material so far relayed to Brippoki. Her intent had been to read on to the end of Druce’s manuscript; also, to complete her transliteration. Except that she had lost her reason.

Sarah smiled a bitter smile – true enough.

A night-cry brought her to the window; animal or human, Sarah could not say. Down below, a single creaking carriage meandered by. Otherwise the street was empty.

Sarah collapsed back into her chair. The book in her lap was

The Night Side of London

, by J. Ewing Ritchie, author of

The London Pulpit

: Lambert had purchased for himself a first edition. Radical in parts – from previous readings the introduction in particular stuck in her mind – the text as a whole amounted to little more than a guide to entertainments found at the more risqué establishments in the celebrated London night (The Mogul Drury-lane, the Cyder Cellars). The slim volume had been slotted away on a high shelf, and Sarah forbidden to look at it.

If Eve had never eaten of the fruit, she and Adam would never have discovered their capacity to act with free will in the world. Aged only sixteen, Sarah had devoured the text – as bitter for the daughter as it had been to the father, although for entirely different reasons. Like so many authors of his sex, Ritchie’s love and passion was for dry statistics. One chapter however, the fourth, happened to concentrate its fetish for lists on Ratcliff-highway. According to Ritchie, in the passages she presently lingered over, a stroll there was sure to shock more senses than one. Having experienced for herself something of the same provocation, Sarah knew this very well to be true. A certain sense of it, the smell most assuredly, would never again leave her thoughts.

Then, as now, men of every colour and creed walked the Ratcliff-highway. George Bruce,

né

Joseph Druce, had been citizen of a ‘rich and racy’ Cosmopolis, a region wherein even an Australian Aborigine might not be considered so very out of place.

J. Ewing Ritchie discussed another common sight along the Highway, women ‘fond of praise, of dress, and pleasure’. He evoked prostitution, simply, as the lesser evil – the slavery and drudgery of the workhouse providing the unpalatable alternative.

Hinting, forcibly, at the sham made of marriage, the author’s commentary rang with at least one harsh and home truth: so long as the ideal of good prospects defined ‘good’ as ‘gold’, great expectations often fell in the way of a successful suit.

Or perhaps she was being a cross old maid.

No city, stated Ritchie, could be more corrupt than London. He pointed the finger of blame squarely at figures in authority: stern parents, divines, and schoolmasters – in short, all forms of government. Lawmakers imprisoned the young alongside the old.

‘You take the little Arab of the streets, and, for acts of levity and wantonness which all boys commit, you send him to prison, at an age when you confess he is not a responsible creature, and then idiotically wonder that he turns out a criminal, and that he wars with society till he is hanged.’

Thus the poor lads received their education, and grew up Ishmaelites.

‘Street Arabs’, just as Sarah had heard Tubridy refer to them, were identified with the sons of Abraham: Isaac was one, and the other Ishmael.

And he will be a wild man: his hand will be against every man, and every man’s hand against him.

Inculcating credo, teaching children catechisms – vaguely telling them to be good – only led to trust in forms rather than truths. Vice, though practised, was scandalously denied. Religion shut its eyes wilfully, refusing to look on life as it was: the Word undermined when not reflected by the act.

‘Is this the way seriously to set about moral reform?’

Ritchie asked in conclusion.

‘Routine and officialism in church and state have made the outside of the sepulchre white enough; do we not need a little cleansing within?

‘How long will men look for grapes from thorns?’

Sarah laid the book down. She did not feel much like reading any more.

The practice of one’s own preaching, heaven knew, was rare enough; she had witnessed evidence of that in her tenderest years. Not from Lambert – he was unimpeachable – but in the behaviour of their guests. Ecclesiasts, by word or action each would offend; and, having offended, would be ejected. Every year fewer and fewer visitors had been admitted, until there were not any at all.

A person’s outward conduct best defined their spiritual character. In setting themselves up as middle-men for God, priests often as not stood in the way of the ordinary person, blocking out the light – because, in their own sinning, by mere profession, they were unqualified. Truth was made for the laity, and Falsehood for the clergy.

Checking in on Lambert, Sarah found him almost too still and quiet. Appalled at herself, she picked up a hand-mirror she had laid aside for that very purpose, and held it, hovering, close to his mouth. She took it up. The glass was smoked. As it cleared, she was left staring almost dumbly at her own reflection: how grey her hair looked, how thin her face.

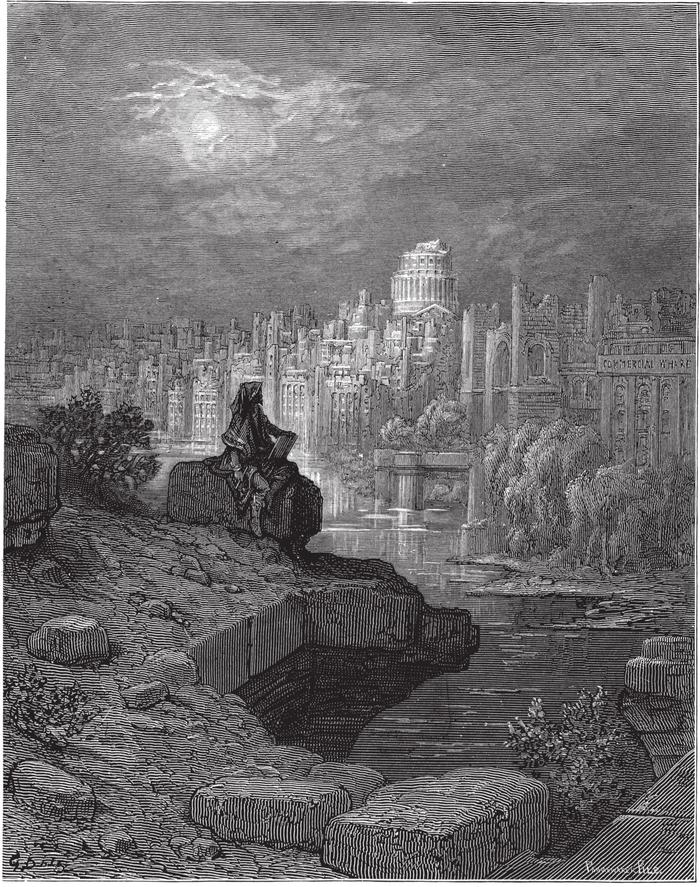

She returned to the parlour; stood, looking into the empty chasm of the street. Often, staring out of that same window, she had believed she could see all of life and London passing her by. It was not nearly all.

The

nachseite

or ‘night side’ of existence was that which was invisible, or sublime; the visible might allude to it, but only if one but knew the signs. She

knew them now: the cheap white muslin, the halfpenny candy cane.

Following the theatre-show and suppertime lull, the vast multitudes of carriages returned. Their wheels ground and set the walls to a slight tremor.

Sarah recognised the true sound of the city. Too consistent for ocean breakers, it was the roar of a cataract endlessly pouring down a gulf.