The Clockwork Universe (8 page)

Read The Clockwork Universe Online

Authors: Edward Dolnick

This was a callous era, both in everyday life and in science. Weakness inspired scorn, not pity. Blindness, deafness, a clubfoot, or a twisted leg were rebukes from God. Entertainments were often cruel, punishments invariably brutal, scientific experiments sometimes macabre. For decades, for example, dissections had been performed in public for ticket-buying audiences, like plays in a theater. The bodies of executed criminals made ideal subjects for study and display and not simply because they were readily available. Just as important, one historian notes, cutting criminals open in front of an attentive audience demonstrated “the culture's preference for punishment by means of public humiliation and display.”

That preference was on display year-round. When it comes to punishing wrongdoers, modern society tends to avert its eyes. Not so the 1600s. In London prisoners locked in the pillory provided a bit of street theater, an alternative to a puppet show. Passersby screamed insults or took the opportunity to show their children what happened to bad people. The captive stood upright as best he could, head and hands trapped in holes cut into a horizontal wooden beam. Perhaps his ears had been nailed to the beam. The pillory was built to pivot as the prisoner staggered, in order to give spectators on all sides a chance to throw a dead cat or a rock.

Since punishments were meant to frighten and demean,

whippings, brandings, and hangings took place where crowds could gather. Thieves could be hanged for stealing a handkerchief, though that was rare. More often, the theft of a handkerchief or a parcel of bread and cheese brought a whipping. A

bolder theftâa gold ring or a silver braceletâmight merit branding

with a hot iron, with a

T

for

thief

. Usually the

T

was seared into the flesh of the hand, although for a brief era that was considered too lenient, and the cheek was used instead. Any substantial theft meant death on the gallows.

Religious dissenters risked terrible punishments, like crimi

nals. For the sin of “horrid blasphemy,” in 1656, the Quaker James

Nayler was sentenced to three hundred lashes, the branding of a

B

on his forehead, and the piercing of his tongue with a red-hot

iron. Then Nayler was flung into prison, where he served three years in solitary confinement.

Even the most gruesome tortures served as spectacle and enter

tainment. (One history of seventeenth-century London includes

an outing to watch a hanging in a section titled “Excursions.”) The most dreadful punishment of all was hanging, drawing, and quartering. “A man sentenced to this terrible fate was strung up by the neck, but not so as to kill him,” the historian Liza Picard explains.

“Then his innards were taken out as if he were a carcass in a butch

er's shop. This certainly killed him, if he had not died of shock before. The innards were burned, and the eviscerated corpse was chopped into four bits, which with the head were nailed up here and there throughout the City.” (To preserve severed heads so that they could endure years of outdoor exposure, and to keep ravens away, they were parboiled with salt and cumin seeds.)

London Bridge in 1616, with traitors' heads on spikes above gateway (right foreground). The heads were such an everyday feature of life that the artist did not bother to call attention to them. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

London Bridge, more or less the shopping mall of its day, had been adorned for centuries with traitors' heads impaled on

spikes. In Queen Elizabeth's day the bridge's southern gate

bristled with some thirty heads.

15

A taste for the grisly ran through the whole society, from the lowliest tradesman to the king himself. On May 11, 1663, Pepys made a passing reference to the king in his diary. Surgeons “did dissect two bodies, a man and a woman, before the King,” Pepys wrote matter-of-factly, “with which the King was highly pleased.”

At times the king's interest in anatomy grew downright creepy. At a court ball in 1663, a woman miscarried. Someone brought the fetus to the king, who dissected it. To modern ears, the lighthearted tone surrounding the whole episode is almost unfathomable. “Whatever others think,” the king joked, “he [i.e., Charles himself ] hath the greatest loss . . . that hath lost a subject by the business.”

When it came to experiments on animals, the seventeenth century was even less squeamish. Newton veered toward vegetarianismâhe seldom ate rabbit and some other common dishes on the grounds that “animals should be put to as little pain as possible”âbut such qualms were rare. Sages of the Royal Society happily carried out experiments on dogs that are too grim to read about without flinching. They had ample company. Descartes, as deep and introspective a thinker as ever lived, wrote blithely that humans are the only animals who think and feel. The yelp of a kicked dog no more indicated pain than did the sound of a drum when you beat it.

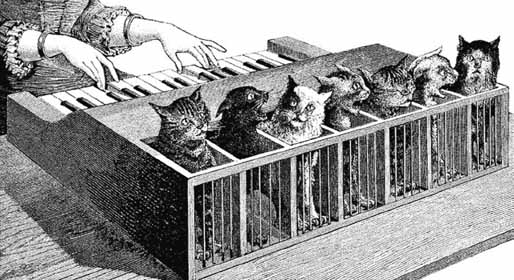

Another widely admired philosopher of the day, Athanasius Kircher, described an odd invention called a cat piano. The goal was to amuse a despondent prince. A row of cats sat in side-by-side cages, arranged according to the pitch of their meows. When the pianist pressed a key, a spike stabbed into the tail of the appropriate cat. “The result was a melody of meows that became more vigorous as the cats became more desperate. Who could help but laugh at such music? Thus was the prince raised from his melancholy.”

In London shouting, jostling crowds flocked to bear-baitings and bull-baitings, where they could watch a chained animal fight a pack of slavering dogs. (Thus the origin of the English bulldog, whose flat face and sunken nose let it keep its hold on a flailing bull without having to open its powerful jaws to breathe.) Even children's games routinely featured the torment of animals. “No wonder,” the historian Keith Thomas writes, “that traditional nursery rhymes portray blind mice having their tails cut off with a carving knife, blackbirds in a pie, and pussy in the well.”

Experiments on dogs were considered entertaining as well as informative. Wren, for instance, made a specialty of splenectomies, surgical operations to remove the spleen. With a dog tied in place on a table, Wren would carefully cut into its abdomen, extract the spleen, tie off the blood vessels, sew up the wound, and then place the poor beast in a corner to recover, or not. (Boyle subjected his pet setter to the procedure and noted that the dog survived “as sportive and wanton as before.”)

The operations provide yet another instance of how new science and ancient belief found themselves yoked together. For fourteen centuries, the Western world had endorsed Galen's doctrine that health depended on a balance of four “humors”âblood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bileâeach secreted by a different organ.

16

Too little or too much phlegm, say, made a person

phlegmatic

, dreary and sluggish and flat. Just as the heart was the source of blood, so the spleen was the source of black bile (which, in the wrong proportion, caused melancholy). All medical authorities had so decreed for more than a thousand years. Hence Wren's experiment, a new test of an age-old dogmaâif health depended on having all four humors in the proper balance, what would it mean if a dog could get along perfectly well with no bile-producing spleen at all?

Countless dogs suffered through transfusions, too. Many of them survived, somehow, even though no one knew about the dangers of infection or mismatched blood types. Boyle wrote a paper calling for answers to such questions “As whether a

fierce

Dog, by being often quite new stocked with the blood of a

cowardly

Dog, may not become more tame,” or “whether a Dog, taught to fetch and carry, or to dive after Ducks, or to sett, will after frequent and full recruits of the blood of Dogs unfit for those Exercises, be as good at them, as before?”

Sometimes the experiments had more serious rationales. How, for instance, did venom from a snakebite spread throughout the body? What about a person who swallowed poison? What would happen if someone injected him with poison instead? Tempting as it might have been to test such ideas on human “volunteers,” dogs came first. (Boyle did report a conversation with “a foreign Ambassador, a very curious person,” who had set out to inject one of his servants with poison. The servant spoiled the fun by fainting before the experiment could begin.)

But many of the experiments were essentially stunts. At dinner one November night in 1666, Pepys listened to an excited report of the events a few days before at the Royal Society. Dr. William Croone gave a vivid account of a blood transfusion between a mastiff and a spaniel. “The first died upon the place,” Pepys reported, “and the other very well, and likely to do well.”

Croone had been impressed by the “pretty experiment” and even suggested to Pepys that someday transfusions might prove useful “for the amending of bad blood by borrowing from a better body.” But no one at the Royal Society had dwelt much on the medical significance of the day's entertainment. The mood

had been carefree, the company devoting most of its attention to

a kind of parlor game. Which natural enemies would make the most amusing partners for a blood exchange? “This did give occasion to many pretty wishes,” Pepys wrote cheerily, “as of the blood of a Quaker to be let into an Archbishop, and such like.”

Pepys's light tone was telltale. Science was destined to remake

the world, but in its early days it inspired laughter more often than reverence. Pepys was genuinely fascinated with

scienceâ

he set up a borrowed telescope on his roof and peered

at the moon and Jupiter, he raced out to buy a microscope as

soon as they came on the market, he struggled through Boyle's

Hydrostatical Paradoxes

(“a most excellent book as ever I read, and I will take much pains to understand him through if I can”), and in the 1680s he served as president of the Royal Societyâbut his amusement was genuine, too.

17

All these in

tellectuals studying spiders and tinkering with pumps. It

was

a

bit ludicrous.

The king certainly thought so. He, too, was an aficionado of science. He had, after all, chartered the Royal Society, and he liked to putter about in his own laboratory. But he referred to the Society's savants as his “jesters,” and once he burst out laughing at the Royal Society “for spending time only in weighing of ayre, and doing nothing else since they sat.”

Weighing the airâwhich plainly weighed nothing at allâseemed less like a groundbreaking advance than a return to such medieval pastimes as debating whether Adam had a navel. Skeptics never tired of satirizing scientists for their impracticality. One critic conceded that the members of the Royal Society were “Ingenious men and have found out A great Many Secrets in Nature.” Still, he noted, the public had gained “Little Advantage” from such discoveries. Perhaps the learned scientists could turn their attention to “the Nature of butter and cheese.”

In fact, they had given considerable thought to cheese, and also to finding better ways to make candles, pump water, tan leather, and dye cloth. From the start, Boyle had taken the lead in speaking out against any attempts to separate science and technology. “I shall not dare to think myself a true naturalist 'til my skill can make my garden yield better herbs and flowers, or my orchard better fruit, or my field better corn, or my dairy better cheese” than the old ways produced.

To hear the scientists and their allies tell it, unimaginable bounty lay just around the corner. Joseph Glanvill, a member of the Royal Society but not a scientist himself, shouted the loudest. “Should those Heroes go on, as they have happily begun,” Glanvill exclaimed, “they'll fill the world with

wonders

.” In the future, “a voyage to Southern unknown Tracts, yea possibly the Moon, will not be more strange than one to America. To them that come after us, it may be as ordinary to buy a

pair of wings

to fly into remotest Regions, as now a pair of Boots to ride a Journey.

”

18

Such forecasts served mainly to inspire the mockers. By 1676 the Royal Society found itself the subject of a hit London comedy, the seventeenth-century counterpart of a running gag on

Saturday Night Live

. The play was called

The Virtuoso

, which could mean either “far-ranging scholar” or “dilettante.” Thomas Shadwell, the playwright, lifted much of his dialogue straight from the scientists' own accounts of their work.

Playgoers first encountered the evening's hero, Sir Nicholas Gimcrack, sprawled on his belly on a table in his laboratory. Sir Nicholas has one end of a string clenched in his teeth; the other end is tied to a frog in a bowl of water. The virtuoso's plan is to learn to swim by copying the frog's motions. A visitor asks whether he has tested the technique in water. Not necessary, says Sir Nicholas, who explains that he hates getting wet. “I content myself with the speculative part of swimming. I care not for the practical. I seldom bring anything to use. . . . Knowledge is my ultimate end.”

Sir Nicholas's family is not pleased. A niece complains that he has “spent £2000 in Microscopes, to find out the nature of Eels in vinegar, Mites in Cheese, and the blue of Plums.” A second niece worries that her uncle has “broken his Brains about the nature of Maggots and studied these twenty Years to find out the several sorts of Spiders.”

All the favorite Royal Society pastimes came in for ridicule. Gimcrack studied the moon through a telescope, as Hooke had done, and his description of its “Mountainous Parts and Valleys and Seas and Lakes,” as well as “Elephants and Camels,” spoofs Hooke's account. (Hooke went to see the play and complained that the audience, which took for granted that he was the inspiration for Gimcrack, “almost pointed” at him in derision.)

Sir Nicholas experimented on dogs, too, and boasted about a blood transfusion in which “the

Spaniel

became a

Bull-Dog

, and the

Bull-Dog

a

Spaniel

.” He had even tried a blood transfusion between a sheep and a madman. The sheep died, but the madman survived and thrived, except that “he bleated perpetually, and chew'd the Cud, and had Wool growing on him in great Quantities.”

Like his king, Shadwell found much to satirize in the virtuosos' fascination with the properties of air. Sir Nicholas keeps a kind of wine cellar with bottles holding air collected from all over. His assistants have crossed the globe “bottling up Air, and weighing it in all Places, sealing the Bottles Hermetically.” Air from Tenerife is the lightest, that from the Isle of Dogs heaviest. Shadwell had great fun with the notion that air is a substance, with properties, rather than a mere absence. “Let me tell you, Gentlemen,” Sir Nicholas assures his visitors, “Air is but a thinner sort of Liquor, and drinks much the better for being bottled.”

Shadwell had a good number of allies among the satirists of his day, many of them eminent. Samuel Butler lampooned men who spent their time staring into microscopes at fleas and drops of pond water and contemplating such mysteries as “How many different Species / Of Maggots breed in rotten Cheeses.”

But no one brought as much talent to ridiculing science as Jonathan Swift. Even writing more than half a century after the founding of the Royal Society, in

Gulliver's Travels

, Swift quivered with indignation at scientists for their pretension and impracticality. (Swift visited the Royal Society in 1710, squeezing in his visit between a trip to the insane asylum at Bedlam and a visit to a puppet show.)

Gulliver observes one ludicrous project after another. He sees men working on “softening Marble for Pillows and Pincushions” and an inventor engaged in “an Operation to reduce human Excrement to its original Food.” In many places, the satire targets actual Royal Society experiments. Real scientists had struggled in vain, for instance, to sort out the mysterious process that would later be called photosynthesis. How do plants manage to grow by “eating” sunlight?

19

Gulliver meets a man who “had been Eight Years upon a project for extracting Sun-Beams out of Cucumbers, which were to be put into Vials hermetically sealed, and let out to warm the Air in raw inclement Summers.”

Swift's sages live in the expectation that soon “one Man shall do the Work of Ten and a Palace may be built in a Week,” but none of the high hopes ever pans out. “In the mean time, the whole Country lies miserably waste, the Houses in Ruins, and the People without Food or Cloaths.”

Mathematicians, the very emblem of head-in-the-clouds

uselessness, come in for extra ridicule. So absentminded are they

that they need to be rapped on the mouth by their servants to remember to speak. Lost in thought, they fall down the stairs and walk into doors. They can think of nothing but mathematics and music. Even meals feature such mathematical courses as “a Shoulder of Mutton, cut into an Equilateral Triangle; a Piece of Beef into a Rhomboides; and a Pudding into a Cycloid.”

In hardheaded England, where “practicality” and “common sense” were celebrated as among the highest virtues, Swift's disdain for mathematics was widely shared by his fellow intellectuals. In that sense, Swift's mockery of absentminded professors was standard issue. But, more than he could have known, Swift was right to direct his sharpest thrusts at mathematicians. These dreamers truly were, as Swift intuited, the most dangerous scientists of all. Microscopes and telescopes were the glamorous innovations that drew all eyesâ

Gulliver's Travels

testifies to Swift's fascination with their power to reveal new worldsâbut new instruments were only part of the story of the age. The insights that would soon transform the world required no tools more sophisticated than a fountain pen.

For it was the mathematicians who invented the engine that powered the scientific revolution. Centuries later, the story would find an echo. In 1931, with great hoopla, Albert Einstein and his wife, Elsa, were toured around the observatory at California's Mount Wilson, home to the world's biggest telescope. Someone told Elsa that astronomers had used this magnificent telescope to determine the shape of the universe. “Well,” she said, “my husband does that on the back of an old envelope.”

Those outsiders who did take science seriously tended to dislike what they saw. The scientists themselves viewed their work as a way of paying homage to God, but their critics were not so sure. Astronomy stirred the most fear. Who needed it, when we already know the story of the heavens and the Earth, and on the best possible authority? To probe further was to treat the Bible as just another source of information, to be tested and questioned like any other. A popular bit of seventeenth-century doggerel purportedly captured the scientists' view: “All the books of Moses / Were nothing but supposes.”

The devout had another objection. Science diverted its practitioners from deep questions to silly ones. “Is there anything more Absurd and Impertinent,” one minister snapped, “than to find a Man, who has so great a Concern upon his Hands as the preparing for Eternity, all busy and taken up with

Quadrants

, and

Telescopes

,

Furnaces

,

Syphons

, and

Air Pumps

?”

So science irritated those who found it pompous and ridiculous. It offended those who found it subversive. Just as important, it bewildered almost everyone.