The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (62 page)

Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

C

APTAIN ALAN JONES

was the S-2 (the equivalent of a division’s G-2) of the Ninth Regiment, which was on the extended eastern front of the Second Division when the Chinese hit. Though resistance had generally been light, in the few days before November 25 there had been an increasing number of skirmishes with some suspected Chinese units. “My map,” Jones said, “was very full of red.” The tension, he thought, was very real in the intelligence shop, and he suspected it was equally high among the infantrymen who were in effect virtually on point for the entire Eighth Army.

This was not the first time Alan Jones, West Point class of 1943, had been in the path of an overwhelming enemy attack in bitterly cold weather. Like Sam Mace, he had been in the Battle of the Bulge as a young officer with the 106th Division, when the Germans suddenly struck the seemingly victorious Allied forces with their last great offensive of the war. His father, Major General Alan Jones, Sr., the commander of the 106th Division, had been uneasy with the idea of having his son in the same unit, but young Alan had wanted to get away from a unit that seemed destined for noncombat duty and to get into a frontline unit. That he got and more. His father, on the eve of battle, was nervous about how extended his division was. He was right, and the German Panzers raced past the 106th on both sides. A message from higher headquarters telling the men to pull back was delayed by heavy radio traffic, and young Alan Jones’s regiment, the 423rd, caught completely by surprise, had fought as best it could before running out of ammo and surrendering. Alan Jones, Jr., was a prisoner of the Germans for some four and a half months, and he vowed that he would never be a prisoner of war again, a vow he repeated with renewed fervor once he landed in Korea and heard the stories of North Korean atrocities against American and ROK POWs.

Jones thought that the Ninth Regiment commander, Colonel Chin Sloane, had positioned his limited forces reasonably well. All three battalions were on the high ground, not too spread out, and under normal conditions they could have supported one another. But there was nothing normal about what

happened that night. Their eastern flank, composed of ROKs, collapsed almost immediately, and then they were hit by wave after wave of Chinese troops. It was as if suddenly there was a brand-new war that began with an attack against the First Battalion—more of a probe, Jones later decided. Then the big hit came around midnight. Jones was at Regimental headquarters when they struck, so he heard the reports as they came in from the three battalions, one report after another, not really panicky, but sharp, strident, with the horror in every word:

they’re hitting us…my God, they’re everywhere…we’re holding, but they’re all over the place…every time we stop them more come…we can no longer hold, there are so many of them…this may be the last message you get from us…

It was not one voice, but several, and the voices kept changing as different radiomen were hit, but it all added up to the same thing, the sound of an American regiment being torn apart by a vastly greater Chinese force. There was no way in that isolated regimental headquarters to measure what was happening—except to know that it was beyond their comprehension. Colonel Sloane was very good in those first few hours, Jones thought. He never lost his calm, never panicked, and did his best to move what remained of the regiment back toward Division, toward a place they hoped would be safer, a place called Kunuri.

12. C

HINESE

A

TTACK

A

T

C

HONGCHON

R

IVER,

O

N

S

ECOND

D

IVISION,

N

OVEMBER

25–26, 1950

There are military disasters that are terrible but are at least momentary. Something horrendous happens to a given unit that has been poorly positioned or poorly led, and the individual unit suffers badly, and then with luck that is the end of it, especially given the ability of the American Army to move men around and protect those under attack. But this was a different kind of disaster. It grew worse hour by hour, as if it had a life of its own. In those early hours, a number of companies in the Thirty-eighth and the Ninth Infantry regiments were virtually wiped out. As that happened, unbearable pressure was placed on adjoining units, and on the battalions and regiments they belonged to, making the entire Second Division vulnerable; it was not exactly like toppling dominoes, but it was close enough for that to be a reasonably accurate description of what was beginning to happen.

AT THE VERY

tip of the most extended finger that represented the Second Division was the Ninth Regiment, and at its very tip was Love Company of the Third Battalion, and at the most forward edge of Love Company was the Second Platoon, commanded by Lieutenant Gene Takahashi of Cleveland, Ohio. Takahashi—Tak, not Gene, to his men—had, as a Japanese-American, spent part of his World War II boyhood in an internment camp in California. Impressed by the exploits of the famed, highly decorated all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Europe—many of whom had come out of the internment camps—and, like them, eager to prove his devotion to his country, he had in 1945 at seventeen volunteered for the United States Army. The only rule given him by his parents when he asked their permission was that he was to do nothing that might disgrace the Takahashi name. He was an unusual officer in an unusual unit—a Japanese-American commanding a platoon of all-black troops. For though the Army was technically desegregated, there were still some all-black units in the early months of the Korean War. The performance of all-black units at that moment, as the Army was changing so quickly, was often uneven, based on who their officers were, whether they were white, and whether they tried to hardass their troops. Takahashi thought his troops were good men and good soldiers. A few were resistant to direct orders, and tone was always important, but if anything, commanding them made him aware of the nuances involved, a sense on occasion that some orders needed to be explained, and he was sure that this had made him a better officer.

As for the prejudices of that era, Takahashi had been well steeped in them, not just from his time in the internment camp but from an earlier tour in Korea. In 1947, while serving as a young officer with the Sixth Division, he had experienced enough prejudice to last a lifetime. His superior had been a West Point graduate, a captain who hated being in Korea, hated Koreans, and, as a

matter of fact, appeared to dislike anyone who looked Asian. The captain took out his frustrations and prejudices by assigning Takahashi every truly crappy job he had. If there was a thankless company task that required a lot of time, was filled with misery, and, even if done well, would bring no credit, Takahashi got it. Someone who was Nisei was still a Jap to the captain, who was clearly out to drive Gene Takahashi from the Army.

Oddly enough, Takahashi decided later, the experience made him a much better officer. He had to plan his time brilliantly. The harder he worked and the better he performed, the angrier it made his superior, who loaded even more work on him. The result, when Takahashi found he couldn’t be broken, was a growing self-confidence, a sense that there was no job in the Army, no matter how unpleasant, that he could not do. The uses of adversity, Gene Takahashi thought, were not to be underestimated.

Gene Takahashi thought Love Company, by dint of all the hard fighting in the Naktong area, had become a reasonably good, battle-tested unit. It would fight well under normal combat conditions—that is, if the men were well positioned and knew what to expect—but not if it was surprised, and unprepared for battle. The men soldiered, he decided, with a far greater index of distrust and a greater wariness of the unknown than the average white soldier. To some degree he believed that reflected the era, when the Army was still partly segregated by race. Many of them—Takahashi understood this all too well himself—had joined the Army to prove something to their country and to escape those very prejudices. To try to prove that those prejudices were unfair and then to encounter them deeply engrained in the Army’s command system was, Takahashi thought, very hard on some of the men.

To a degree, the company reflected the personality of the company commander, Captain Maxwell Vails, a very decent officer. Vails was a strong, earthy figure, with a good feel for the mood of the men, who in turn liked and respected him, which was no small thing. But whether he had any real feel for combat, for what to do when bad things happened (and in this war, bad things were always happening), was another question entirely. It was also an important one, essentially about what distinguished a great officer from an ordinary or even a good one. There was a private sense on the part of some of the men—and Takahashi agreed—that when their superiors had a dirty assignment, like trying to find out if the North Koreans were secretly dug in on top of a given hill, in effect like pushing a stick into a beehive, it was a little more likely that they would choose Love Company for the probe.

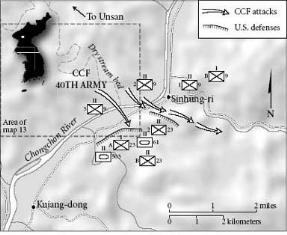

As far as most of the men in Love Company were concerned, by mid-November, the war had largely disappeared. On the day that the great offensive began, they were all still quite upbeat. They crossed the Chongchon River on the

first day, at a place near Kujang-dong, leaving most of their supplies behind, including bedding, extra ammo, and grenades. The trucks and jeeps simply could not go any farther, because of the terrain. Perhaps they would catch up a little later. Takahashi later faulted himself for not insisting the men take as many grenades as they could—if he had loaded each man up with grenades, it might have made a difference when the Chinese struck. They did not even have their overcoats with them. They had left these back at the last CP. They did not expect to be gone long. The Chongchon was not very deep, just up to their waists, but it was very cold. Crossing it was not hard, but they made one mistake: they wore their pants, whereas the Chinese, more expert at this—they had learned so much from the Long March—took their pants off for such crossings, which meant that the cold and wet were not embedded in their clothes and did not last as long. The soldiers of Love Company then spent hours of that freezing day soaked and climbing a high mountain about a mile and a half from the river, before setting up for the night. The one thing that put Takahashi on notice was a series of almost perfect foxholes he came across, three feet deep each, and each one a replica of the next, absolutely square, as if done by some expert in landscaping. This was the work of men who knew how to do the little things well. Americans dug their foxholes haphazardly, because they always expected to have superior firepower. The In Min Gun were not much better. These foxholes suggested strongly that a new player was in the game. In the mid-afternoon of November 24, Love Company set up its perimeter just east of the Chongchon.

They were on a relatively high point about three miles north of the tiny village of Kujang-dong, which existed more on maps than in reality—although later, when they all tried to figure out where the Chinese attack had taken place and where so many friends had died, at least it gave them a location on the map. Takahashi, who argued briefly with Captain Vails on the subject, did not like the way the men had been positioned. He thought their perimeter was too much of a straight line and not concentrated on what he was sure were the likely avenues of approach. Lieutenant Dick Raybould, a young forward observer for the Thirty-seventh Field Artillery, whose job it was to support Love Company, agreed. He felt Captain Vails had been too casual in positioning his men. Raybould, who was new to the company, was also surprised when Vails set up his CP on the back side of a hill, a little too sheltered, he felt. Worse, Raybould believed, Vails had assigned different sectors to his three platoon leaders and let them set up for themselves, thus creating a defensive perimeter that did not reflect the hill’s contours. They did not have good interlocking fields of fire, and they might, he thought, be vulnerable to flanking movements. Takahashi agreed; he wanted a tighter perimeter, formed in more of a circle to fit the contours, but he had not been able to change Vails’s mind.

The fires that they set bothered Raybould too. As far as he was concerned it was like giving your enemy a set of beacons to find you. He saw the men’s fires early in the evening and went over to the company command post to complain, only to discover that the biggest fire of all was the one that warmed the company commander, a huge bonfire. A very new lieutenant does not argue with a captain, but later Raybould was sure the fires had served the Chinese well. Takahashi was not so sure the fires were a mistake. As darkness fell, his men were still wearing wet clothes, and he had sent them back, two at a time, to a place he had set up with a small fire, where they could dry their clothes.