The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (76 page)

Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

The other thing they were going to do was know their enemy—one more sign that the days of grandiose contempt for an Asian enemy, so racist in its origins, were over. More than most senior American commanders of his era, Matt Ridgway had a passion for intelligence. The American Army had always taken its intelligence functions somewhat casually; the men assigned to intelligence duty tended to have been passed over in their careers, not quite good enough for the prized command positions. Often the lower ranks in the Army’s intelligence shop were very good, but their superiors were not respected by their peers. Perhaps it was the nature of the modern American Army—it had so much force and materiel that when it finally joined battle, intelligence tended to be treated as a secondary matter, on the assumption that any enemy could simply be outmuscled and ground down.

There were a number of reasons for Ridgway’s obsession with intelligence. Some of it was his own superior intellectual abilities; he was simply smarter than most great commanders. Some of it was his innate conservatism, his belief that the better your intelligence, the fewer of your own men’s lives you were likely to sacrifice. A great deal of it was his training in the airborne, where you made dangerous drops behind enemy lines with limited firepower and were almost always outnumbered and vulnerable to larger enemy forces. Certainly, his wariness about joining Marshal Badoglio in taking Rome reflected an airborne officer’s insistence that his intelligence be the best. George Allen—who as a young CIA field officer in Vietnam briefed Ridgway daily for several weeks as the French war in Indochina was coming to its climax in 1954, later said he had never dealt with a man so acute and demanding, not even Walter Bedell Smith, who had been Dwight Eisenhower’s tough guy in Europe and later took over the CIA. Ridgway’s sense of the larger picture was so accurate, Allen believed, because of his determination to get the smallest details right. It was Ridgway’s subsequent report on what entering the war in Indochina would mean—five hundred thousand to one million men, forty engineering battal

ions, and significant increases in the draft—that helped keep America out of the war for a time.

Charles Willoughby, one colleague said, would have lasted about an hour on Ridgway’s staff. The CIA, blocked from the Korean theater by MacArthur and Willoughby, was soon welcomed back. Starting at Eighth Army headquarters and running through the command, there was going to be a healthy new respect for the enemy. The Chinese had identifiable characteristics on the battlefield. They also had good, tough soldiers. Some units were clearly better than others, some division commanders better than others, and it was vital to know which these were and where they were. Now Ridgway intended to study them. There would be no more windy talk about the mind of the Oriental. The questions would be: How many miles can they move on a given night? How fixed are their orders once a battle begins? How much ammo and food do they carry into each battle—that is, how long can they sustain a given battle? Ridgway was going to separate battlefield realities from theoretical discussions about the nature of Communism. The essential question was: How

exactly

can we tilt the battlefield to our advantage?

Ridgway now intended to play at least as big a role in the selection of the battlefield as his Chinese opposites. For a time, he started his day by getting in a small plane and, with Lynch at the controls, flying as low as they could, looking for the enemy. With that many Chinese coming at his army, there had to be signs of them, evidence that they existed, but he saw almost nothing. That he found nothing did not, as had happened in November after Unsan, create a lack of respect for them—rather it brought greater respect for the way they could move around seemingly invisible. Gradually Ridgway began to put together a portrait of who the Chinese were and how they fought—and so, how he intended to fight them. The Chinese were good, no doubt about that. But they were not supermen, just ordinary human beings from a very poor country with limited resources. Not only did the Chinese operate from a large technological disadvantage, they had significant logistical and communications weaknesses. The bugles and flutes announcing their attacks could be terrifying in the middle of the night, but the truth was that, with only musical instruments, they could not react quickly to sudden changes on the battlefield. If they had a breakthrough, they often lacked the capacity to exploit it immediately. That was a severe limitation; it meant that a great deal of blood might be shed without their getting adequate benefits. In addition, certain logistical limitations were built into any attack they made—the ammunition and food they could carry was finite indeed. The American Army could resupply in a way inconceivable to the Chinese and so could sustain a given battle far longer.

Ridgway spent his first few weeks in country pressing everyone for infor

mation about the Chinese fighting machine. By the middle of January, he felt he knew much of what he needed to know. This war, he decided, was no longer going to be primarily about gaining terrain as an end in itself, but about selecting the most advantageous positions available, making a stand, and bleeding enemy forces, inflicting maximum casualties on them. The key operative word would be “pyrrhic.” What he now sought was an ongoing confrontation in which every battle resulted in staggering losses for the Chinese. At a certain point, even a country with a demographic pool like China’s had to feel the pain from the loss of good troops. He wanted to speed up that moment, to let his adversaries know that there were no more easy victories out there for the picking, no second shot at a big surprise attack. If the war was to be a grinder then the great question was: which side would do the more effective job of grinding up the other?

The first thing Ridgway realized was that it was a disaster to retreat once the Chinese hit. The key to their offensive philosophy was to stab at a unit, create panic, and then, from advantageous positions already set up in its rear, maul it when it retreated. All armies are vulnerable in retreat, but an American unit, because of all its hardware, condemned to the narrow, bending Korean roads, was exceptionally so. What the Chinese had done at Kunuri, Ridgway learned, matched their MO when they fought the Nationalists in their civil war. But no one, it appeared, had been paying much attention. The disaster at Kunuri, he believed, had not been writ so large because the Chinese were such magnificent soldiers or even had such an overwhelming advantage in manpower. Even as far north and as vulnerable as they were, if the American units had been well buttoned down at night, if each unit had had interlocking fields of firepower with reliable flanking units (and had not counted on the ROKs to protect them), the outcome of the battle might have been different. Even at Kunuri, the military had had the capacity to resupply the troops by air until the Chinese were exhausted. Ridgway’s long training as an airborne man was critical to the strategy he sought now. He meant to create strong islands of his own, sustain unit integrity with great fields of fire, and then let the enemy attack. It was, he believed, why Colonel John Michaelis, with his Twenty-seventh Regiment Wolfhounds, had been so much more successful than other regimental commanders in the early part of the war. Michaelis was an airborne guy, and he did not mind if his men were cut off as long as unit integrity was preserved. He knew he could always be resupplied by air.

What Ridgway wanted to do was start the Eighth Army moving north again—for reasons of morale as much as anything. In mid-January, he began the process, sending Michaelis’s unit toward Suwon. He named this first offensive action Operation Wolfhound in their honor. Michaelis had known Ridgway

before Korea, but not well. Still, he had been struck by Ridgway’s fierce beetle-eyed glare—that was how he would later describe it—that went right through you. Ridgway had been in Korea only a few days when he called him in.

“Michaelis, what are tanks for?” he asked.

“To kill, sir.”

“Take your tanks to Suwon,” Ridgway said.

“Fine, sir,” Michaelis answered. “It’s easy to get them there. Getting them back is going to be more difficult because they [the Chinese] always cut the road behind you.”

“Who said anything about coming back?” Ridgway answered. “If you can stay up there twenty-four hours, I’ll send the division up. If the division can stay up there twenty-four hours, I’ll send the corps up.” That, thought Michaelis, was the start of a brand-new phase of the war, the beginning of the turnaround. Without the Chinese leadership realizing it, a very different UN force was coming together in Korea.

T

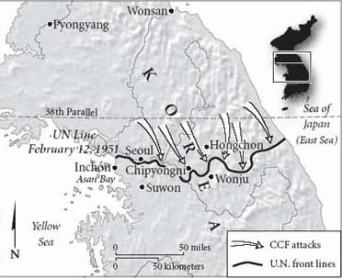

HE CHINESE WERE

about to encounter a very different American command structure, and thus a very different American Army, in three battles in mid-February 1951, at Twin Tunnels, Chipyongni, and Wonju. But even before the two forces collided there, significant fissures had been appearing in the Chinese command structure. They had first showed up during the earliest discussions between China’s military and political leaders, in September and October 1950, when Mao was pondering the question of intervention. Back then Lin Biao had opposed the coming war, fearing greatly superior American firepower that the Chinese could not possibly match. He argued that the firepower of an American division was roughly ten to twenty times greater than that of its Chinese equivalent. He and some of the other military men made an additional point: there was such a vast gap between U.S. capabilities, given the country’s awesome industrial base, and China’s limited ability to sustain a modern war, that replenishing equipment alone might prove a crisis in itself.

The fact that Lin had even made the argument—before excusing himself from an unwanted command because of alleged problems with his health—reflected a deep uneasiness among many of the Chinese military men, as well as the almost complete supremacy of the political people. They were all political men, of course, even the military men understood that; their basic doctrine made clear that political realities came first, military ones second. This was how and why they had been so successful in their long, demanding civil war. Their lack of an ability to replenish their weaponry had not been a problem—they had always been able to capture additional weapons from Chiang’s forces. Their doctrines had all been based on almost unshakeable political truths in that war, but it had been waged on

Chinese soil,

where their ease in gaining and holding the loyalty of the peasants, long denied elemental dignity and basic economic rights, gave them an unassailable advantage. Whether the same dynamic would work in a foreign land was an open question, even if it was an Asian one with a comparably aggrieved peasant population and where in the

North, at least, the Chinese represented an ostensibly fraternal Communist party. If politics, as Mao believed, had its special truths that they knew better than anyone else, then military men like Peng Dehuai, political though they also were, knew that the battlefield had its truths as well. The political and military truths had dovetailed perfectly during the Chinese civil war, but they would separate in Korea, where Chinese troops in the eyes of most Koreans would be simply another foreign army and where the appearance of Chinese soldiers would have its own colonial implications.

After the battles along the Chongchon, Mao was ever more confident; Marshal Peng on the other hand was aware that much of his success had stemmed from the fact that the Americans had stupidly stumbled into a trap. He was concerned as his troops headed south; he had no air cover, and his logistical limitations were clear to him from the start. In Mao’s mind, however, the Americans had behaved as he had predicted, as capitalist pawns pressed reluctantly into an unwanted war. There were times now, as the Chinese moved south and Mao pressed for a more aggressive strategy, that Peng would shake his head, turn to his aide, Major Han Liquin, and complain about Mao becoming drunk with success. In Peng’s much more conservative view, there had already been serious signs of the difficulties ahead. Just feeding his vast army was a problem—in much of December they had gotten by subsisting largely on rations that the Americans had left behind, but their troops were now, he felt, half-starved. If they drove even farther south, the problem of feeding, and supplying his army with ammo, would be even worse.

When his forces had caught the Americans utterly ill-prepared at the Chongchon River, even when they had isolated an American unit, they often found it difficult to finish that unit off, especially given the U.S. control of the skies. (That complete control had occasioned a certain droll humor among the crews of American antiaircraft guns. When fighters or bombers flew overhead, the men would identify them as “B-2s.” As yet there was no B-2 bomber in the Air Force inventory, so some soldier not yet clued in would ask in surprise, “What’s a B-2?” And the answer would invariably come back, “

Be too

bad if they weren’t ours.”) U.S. firepower was, as advertised, exceptional, and because of the Americans’ airpower and the mobility of their ground forces, they had a capacity to come to the rescue of isolated units that the Chinese had never seen before.

Even at Kunuri, far more of the American fighting force had escaped than Chinese planners had imagined possible given the total surprise the Chinese achieved and the incompetence of the senior American command. But it was during what the Chinese called the Fourth Campaign, or Fourth Phase, that

their vulnerabilities became fully apparent and tensions between the field commanders and the political men making the decisions broke into the open. The First Campaign had lasted from October 24 to November 5 and focused on the destruction of the ROK forces leading the advance north and then of the Eighth Cav at Unsan; the Second Campaign was the assault along the Chongchon and against the Marines at the Chosin Reservoir in late November and early December. The Third Campaign took place in early January after much debate between Mao and Peng, who wanted to delay it, sensing that his exhausted troops were being pushed too hard for political reasons. It involved a quick push south behind the retreating Americans, during which Seoul, the Southern capital, changed hands for the third time in six months. As the campaign ended, the lead Chinese armies found themselves deep in the South, at the thirty-seventh parallel. The Fourth Campaign, presumably to start in January, would be the big one, the one that Mao hoped would take them perhaps another hundred miles farther south and leave them ready to strike at Pusan.

But as the Americans retreated down the long, thin peninsula, the Chinese began to experience some of the very problems that had frustrated their enemies—most particularly the problem of extended supply lines in a country with primitive roads and rail systems. Because they lacked air and sea power, this was a significantly more serious problem for them. When the Americans had moved north, they had been able to use trucks and trains without fear of being attacked from the air. They could, if necessary, transport badly needed ammo and food by air and sea. Not only did the Chinese have far fewer motorized vehicles to supply a vast army, but the trucks and trains were a perfect target for the ever stronger American air wing. It was Mao’s turn now to be distanced from the battlefield, and to see it, as MacArthur had, not as it actually was, but as he wanted it to be in his mind. Mao had misread the easy early victory up north, even as some of his commanders understood why it might not happen so readily again. As the historian Bin Yu noted, Mao now “encouraged by China’s initial gains began to pursue goals that were beyond [his] force’s capabilities.” That placed the burden of dealing with reality squarely on Peng’s shoulders.

In a way Peng was an almost perfect counterpart to Ridgway—they could not have been more similar in what drove them and the way they saw and handled their own men. It would not be hard to imagine some switch in ancestry and an American version of Peng commanding the UN forces, and Ridgway, in a Chinese incarnation, the Chinese. Like Ridgway, Peng was a soldier’s soldier, unusually popular with his men, because he was sensitive to their needs. The

more successful he became, the truer he remained to what he had been. Sometimes when his troops were moving long distances on foot, and other peasants, or coolies as Westerners called them, were serving primarily as bearers, carrying heavy loads strung over poles, he would take the pole from one of them and take a turn himself, which greatly impressed the troops and served to remind everyone—his men and himself—where it had all begun and, perhaps equally important,

why

it had begun. He was a man absolutely without pretension, which endeared him greatly to his troops. During the Long March, out of personal devotion, his men had twice carried him for long distances on a litter after he had been struck down with a severe fever. On one occasion when he was very sick in Sichuan, his men had refused to leave him behind; nursing him and carrying him along was their way of thanking him for the humane way he had always treated them.

He was straightforward and no less blunt than Ridgway. It amused him when some of his former colleagues in what had been in the beginning a peasant army began to take on airs once they defeated the Nationalists. Peng still preferred to bathe in cold water, even when hot water was available, because he had always done so, and because this was what peasants did. In his lifestyle he preferred an almost monastic simplicity, and was uneasy with unwanted creature comforts. He preferred curing illnesses with herbs rather than modern medicines prescribed by doctors, and he always ate very slowly, deliberately so, he said, because he liked to think of the days when they had first started out, always hungry. Now that he had enough food, he intended to savor it.

Peng was a good deal shrewder than some of the other people in the politburo gave him credit for. He had never been fooled by his early success up along the Chongchon. Even before the war began, he had believed that, given the unusual nature of the Korean peninsula, the opposing armies would have a terrible time getting supplies to either end of the country. “Korea,” he had told his staff before the war began, “will be a battle of supply.” That was why he argued successfully with Mao that when they hit the Americans all-out for the first time, they should do it from positions as far north as possible.

But he also knew in what were for him the heady, good days of November and December how near the bad days might be. In the period after the success of the Second Offensive in late November, he was quite shrewd in sizing up the residual strength of the defeated American forces, and the price his troops had already paid, especially around the Chosin Reservoir. The Marines had fought back with a ferocity that belied Mao’s convictions about how the soldiers of a capitalist army would perform. When Peng spoke with his senior people, he would on occasion let a certain sarcastic note enter his voice about Mao—“some self-proclaimed experts on the art of war,” or “some military experts,” or “some people who see the conduct of war in dogmatic terms.” He was furious when both the Russians and North Koreans argued strongly in December that

his

troops should pursue the Americans more aggressively. The Russians were not putting

their

men into the field, and as for the North Koreans, he was bailing them out from their own incredible mistakes and poor leadership. He hated the pressure they put not so much on him, but on Mao, to move more rashly, the implication being that the Chinese were showing the world that they were not as good Communists, or as brave as Russians might have been in the same circumstances.

19. T

HE

F

IGHT

F

OR

T

HE

C

ENTRAL

C

ORRIDOR

Peng’s constant mantra with his staff was the need for supplies. He had, at the start, commanded an army of some three hundred thousand men, and it grew even larger as he prepared for future battles. As he had predicted, the logistics were a nightmare: in December, he had at most three hundred trucks to ferry supplies to his men, and those trucks had to travel in the dark with their lights off, making at best a total of twenty to thirty miles a night. Resupply of both ammunition and food became the great vulnerability of his army. On the

Chinese side much of the logistical support was done not by trucks but by Chinese bearers, who carried food and supplies south to Peng’s men, often on foot over enormous distances, and who, that part of the journey done, carried the wounded back north. Under these circumstances, much of his army existed, once it neared the thirty-eighth parallel, on a diet that was just a bit above starvation levels. Foraging was unpromising: as they moved back and forth across the Korean peninsula, both sides destroyed land and crops, something that weighed more harshly on the Chinese forces than on the Americans, who did not have to eat off the land. A cruel, arctic winter ensured that there was no abundant local food source for the Chinese troops; if Mao’s soldiers had, to use his famous phrase, been the fish swimming in the ocean of China’s peasants not so long before, now they were swimming in more hostile waters. The Korean peasants turned out to be just as dismayed to see them as they were to see the Americans or the ROKs, for almost nothing good happened once the war arrived in your village. As a result, malnutrition was a serious problem. Peng’s soldiers had, in the phrase used in those days, to fight their hunger with “one bite [of] parched flour and one bite [of] snow.” When their buddies were killed, they often scavenged their bodies for extra bullets and any extra food they could find.