The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight (22 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

In that way, the invocation of the drala principle allows us to live in harmony with the elemental quality of reality. The modern approach often seems to be one of trying to conquer the elements. There is central heating to conquer winter’s cold, and air conditioning to conquer summer’s heat. When there is drought or flooding or a hurricane, it is seen as a battle with the elements, as an uncomfortable reminder of their strength. The warrior’s approach is that, rather than trying to overcome the raw elements of existence, one should respect their power and their order as a guide to human conduct. In the ancient philosophies of both China and Japan, the three principles of heaven, earth, and man expressed this view of how human life and society could be integrated with the order of the natural world. These principles are based on an ancient understanding of natural hierarchy. I have found that, in presenting the discipline of warriorship, the principles of heaven, earth and man are very helpful in describing how the warrior should take his seat in the sacred world. Although politically and socially, our values are quite different from those of Imperial China and Japan, it is still possible to appreciate the basic wisdom contained in these principles of natural order.

Heaven, earth, and man can be seen literally as the sky above, the earth below, and human beings standing or sitting between the two. Unfortunately, the use of “man” here, rather than “human being,” may have a limiting connotation for some readers. (By “man,” in this case, we simply mean anthropomorphic existence—human existence—not man as opposed to woman.) Traditionally, heaven is the realm of the gods, the most sacred space. So, symbolically, the principle of heaven represents any lofty ideal or experience of vastness and sacredness. The grandeur and vision of heaven are what inspire human greatness and creativity. Earth, on the other hand, symbolizes practicality and receptivity. It is the ground that supports and promotes life. Earth may seem solid and stubborn, but earth can be penetrated and worked on. Earth can be cultivated. The proper relationship between heaven and earth is what makes the earth principle pliable. You might think of the space of heaven as very dry and conceptual, but warmth and love also come from heaven. Heaven is the source of the rain that falls on the earth, so heaven has a sympathetic connection with earth. When that connection is made, then the earth begins to yield. It becomes gentle and soft and pliable, so that greenery can grow on it, and man can cultivate it.

Then there is the man principle, which is connected with simplicity, or living in harmony with heaven and earth. When human beings combine the freedom of heaven with the practicality of earth, they can live in a good human society with one another. Traditionally it is said that, when human beings live in harmony with the principles of heaven and earth, then the four seasons and the elements of the world will also work together harmoniously. Then there is no fear and human beings begin to join in, as they deserve, in living in this world. They have heaven above and earth below, and they appreciate the trees and the greenery and so on. They begin to appreciate all this.

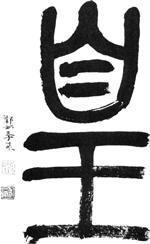

But if human beings violate their connection, or lose their trust in heaven and earth, then there will be social chaos and natural disasters. In Chinese the character for the ruler, or king, is a vertical line joining three horizontal lines, which represent heaven, earth, and man. This means that the king has the power to join heaven and earth in a good human society. Traditionally, if there was plenty of rainfall, and crops and vegetation flourished, then this indicated that the king was genuine, that he truly joined heaven and earth. But when there was drought and starvation or natural catastrophes, such as flooding and earthquakes, then the power of the king was in doubt. The idea that harmony in nature is linked to harmony in human affairs is not purely an Oriental concept. For example, there are many stories in the Bible, such as the story of King David, that portray the conflict between heaven and earth and the doubt that it raises about the king.

If we apply the perspective of heaven, earth, and man to the situation in the world today, we begin to see that there is a connection between the social and the natural, or environmental, problems that we are facing. When human beings lose their connection to nature, to heaven and earth, then they do not know how to nurture their environment or how to rule their world—which is saying the same thing. Human beings destroy their ecology at the same time that they destroy one another. From that perspective, healing our society goes hand in hand with healing our personal, elemental connection with the phenomenal world.

The Chinese character for emperor. The bottom half is the character for the ruler or king described in this chapter

.

CALLIGRAPHY BY SHENG-PIAO KIANG. PHOTOGRAPH BY GEORGE HOLMES.

When human beings have no sense of living with a wide open sky above and a lush green earth below, then it becomes very difficult for them to expand their vision. When we feel that heaven is an iron lid and that earth is a parched desert, then we want to hide away rather than extending ourselves to help others. Shambhala vision does not reject technology or simplistically advocate going “back to nature.” But within the world that we live in, there is room to relax and appreciate ourselves and our heaven and our earth. We can afford to love ourselves, and we can afford to raise our head and shoulders to see the bright sun shining in the sky.

The challenge of warriorship is to live fully in the world as it is and to find within this world, with all its paradoxes, the essence of nowness. If we open our eyes, if we open our minds, if we open our hearts, we will find that this world is a magical place. It is not magical because it tricks us or changes unexpectedly into something else, but it is magical because it can

be

so vividly, so brilliantly. However, the discovery of that magic can happen only when we transcend our embarrassment about being alive, when we have the bravery to proclaim the goodness and dignity of human life, without either hesitation or arrogance. Then magic, or drala, can descend onto our existence.

The world is filled with power and wisdom, which we can have, so to speak. In some sense we have them already. By invoking the drala principle, we have possibilities of experiencing the sacred world, a world which has self-existing richness and brilliance—and beyond that, possibilities of natural hierarchy, natural order. That order includes all the aspects of life—including those that are ugly and bitter and sad. But even those qualities are part of the rich fabric of existence that can be woven into our being. In fact, we are woven already into that fabric—whether we like it or not. Recognizing that link is both powerful and auspicious. It allows us to stop complaining about and fighting with our world. Instead, we can begin to celebrate and promote the sacredness of the world. By following the way of the warrior, it is possible to expand our vision and give fearlessly to others. In that way, we have possibilities of effecting fundamental change. We cannot change the way the world

is,

but by opening ourselves to the world

as it is,

we may find that gentleness, decency, and bravery are available—not only to us, but to all human beings.

SEVENTEEN

Natural Hierarchy

Living in accordance with natural hierarchy is not a matter of following a series of rigid rules or structuring your days with lifeless commandments or codes of conduct. The world has order and power and richness that can teach you how to conduct your life artfully, with kindness to others and care for yourself.

T

HE PRINCIPLES OF HEAVEN,

earth, and man that were discussed in the last chapter are one way of describing natural hierarchy. They are a way of viewing the order of the cosmic world: the greater world of which all human beings are a part. In this chapter, I would like to present another way of seeing this order, which is part of the Shambhala wisdom of my native country of Tibet. This view of the world is also divided into three parts, which are called lha, nyen, and lu. These three principles are not in conflict with the principles of heaven, earth, and man, but as you will see, they are a slightly different perspective. Lha, nyen, and lu are more rooted in the laws of the earth, although they acknowledge the command of heaven and the place of human beings. Lha, nyen, and lu describe the protocol and the decorum of the earth itself, and they show how human beings can weave themselves into that texture of basic reality. So the application of the lha, nyen, and lu principles is actually a further way to invoke the power of drala, or elemental magic.

Lha

literally means “divine” or “god,” but in this case, lha refers to the highest points on earth, rather than a celestial realm. The realm of lha is the peaks of snow mountains, where glaciers and bare rock are found. Lha is the highest point, the point that catches the light of the rising sun first of all. It is the places on earth that reach into the heavens above, into the clouds; so lha is as close to the heavens as the earth can reach.

Psychologically, lha represents the first wakefulness. It is the experience of tremendous freshness and freedom from pollution in your state of mind. Lha is what reflects the Great Eastern Sun for the first time in your being and it is also the sense of shining out, projecting tremendous goodness. In the body, lha is the head, especially the eyes and forehead, so it represents physical upliftedness and projecting out as well.

Then, there is

nyen,

which literally means “friend.” Nyen begins with the great shoulders of the mountains, and includes forests, jungles, and plains. A mountain peak is lha, but the dignified shoulders of the mountain are nyen. In the Japanese samurai tradition, the large starched shoulders on the warriors’ uniforms represent nyen principle. And in the Western military tradition, epaulets that accentuate the shoulders play the same role. In the body, nyen includes not only your shoulders but your torso, your chest and rib cage. Psychologically, it is solidity, feeling solidly grounded in goodness, grounded in the earth. So nyen is connected with bravery and the gallantry of human beings. In that sense, it is an enlightened version of friendship: being courageous and helpful to others.

Finally, there is

lu,

which literally means “water being.” It is the realm of oceans and rivers and great lakes, the realm of water and wetness. Lu has the quality of a liquid jewel, so wetness is connected here with richness. Psychologically, the experience of lu is like jumping into a gold lake. Lu is also freshness, but it is not quite the same as the freshness of the glacier mountains of lha. Here, freshness is like sunlight reflecting in a deep pool of water, showing the liquid jewellike quality of the water. In your body, lu is your legs and feet: everything below your waist.

Lha, nyen, and lu are also related to the seasons. Winter is lha; it is the loftiest season of all. In the winter, you feel as if you were upstairs, above the clouds; it is cold and crisp, as if you were flying in the sky. Then there is spring, which is coming down from heaven and beginning to contact earth. Spring is a transition from lha to nyen. Then there is summer, which is the fully developed level of nyen, when things are green, in full bloom. And then summer develops into autumn, which is related with lu, because fruition takes place, the final development. The fruit and harvest of the autumn are the fruition of lu. In the rhythm of the four seasons, lha, nyen, and lu interact with one another in a developmental process. This applies to many other situations. The interaction of lha, nyen, and lu is like snow melting on a mountain. The sun warms the peaks of the mountain, and the glaciers and snow begin to melt. This is lha. Then the water runs down the mountainside to form streams and rivers, which is nyen. Finally, the rivers converge in the ocean, which is lu, the fruition.

The interaction of lha, nyen, and lu also can be seen in human interactions and behavior. For example, money is lha principle; establishing a bank account and depositing your money in the bank is nyen; and drawing money out of the bank to pay your bills or to buy something is lu. Or another example is as simple as having a drink of water. You can’t drink water out of an empty glass, so first you pour water into the glass, which is the place of lha. Then you pick up the glass in your hands, which is nyen. And finally you drink, which is the place of lu.

Lha, nyen, and lu play a role in every situation in life. Every object you handle is connected with one of those three places. For example, in terms of clothing, the hat is in the place of lha, the shoes are in the place of lu, and shirts, dresses, and trousers are in the place of nyen. If you mix up those principles, then you instinctively know that something is wrong. For instance, if the sun is beating on your head, you don’t put your shoes on your head as a visor to protect you from the sun. And on the other hand, you don’t walk on your eyeglasses. You don’t stuff your shoes with your ties and, for that matter, you shouldn’t put your feet on the table, because it is mixing up lu and nyen. Personal articles that belong to the lha realm include hats, glasses, earrings, toothbrushes, and hairbrushes. Articles belonging to the realm of nyen are rings, belts, ties, shirts and blouses, cuff links, bracelets, and watches. Articles belonging to the place of lu include shoes and socks and underwear. I’m afraid it is as literal as that. Lha, nyen, and lu are quite straightforward and very ordinary.