The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight (28 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

Over the centuries, there have been many who have sought the ultimate good and have tried to share it with their fellow human beings. To realize it requires immaculate discipline and unflinching conviction. Those who have been fearless in their search and fearless in their proclamation belong to the lineage of master warriors, whatever their religion, philosophy, or creed. What distinguishes such leaders of humanity and guardians of human wisdom is their fearless expression of gentleness and genuineness—on behalf of all sentient beings. We should venerate their example and acknowledge the path that they have laid for us. They are the fathers and mothers of Shambhala, who make it possible, in the midst of this degraded age, to contemplate enlightened society.

Afterword

I

N

1975 the Venerable Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche gathered a small group of students, myself among them, and introduced a secular discipline, which he called the teachings of Shambhala. He explained that this discipline, which we now call Shambhala Training, was appropriate for all beings, regardless of the conditions of their birth, status, or previous beliefs. As devoted and keen students of the path of buddhadharma, we listened to these first presentations with mixed emotions. Although Trungpa Rinpoche had often introduced us to new topics and projects without warning, this vision of warriorship and enlightened society was so vast and profound that it was at once exciting and threatening.

When Trungpa Rinpoche first presented the buddhadharma in the West, especially in North America, it was as if a lightning bolt illuminated a dark sky. Buddhism had been taught in the West for quite some time, but not until Trungpa Rinpoche’s direct connection with the language and custom did the reality of dharma become part of Western culture. This is not to say that the authentic dharma had not been transmitted, nor that no previous contribution had been made to the establishment of Buddhism in the West. Many teachers, in particular Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, had spent their lives transmitting the ancient lineage of the Buddha to Western students. Because the ground had been prepared, the meeting of minds between Trungpa Rinpoche and his students and the Western world altogether was spontaneous and illuminating. The introduction of the teachings of Shambhala was likewise sudden and startling.

Rinpoche himself was without hesitation or fear in presenting Shambhala wisdom, as he was when he presented Buddhism to his Western students. In fact, he never seemed to make a distinction between Eastern and Western when discussing the nature of things. We began to see in him an entirely new dimension as a teacher. That was unexpected, to say the least. It was almost like discovering the existence of some lost treasure. When he manifested as the Dorje Dradül, the “indestructible warrior,” it was as though he were always seated majestically on a white stallion. His brilliance was uncontrived, impeccable, and elegant. He taught appreciation of ordinary things and introduced forms that in the world of modern casualness seemed outrageous. Being bred on the notion that informality equals relaxation, we resisted. But his way of working with the world was so uplifting, joyous, and delightful that it did not take any convincing to know this was the real way to be. One could be dignified and genuine, with a sense of formality, without being stiff or tight.

The Dorje Dradül’s way of being was an expression of respect for the world and for others. He could demonstrate this by the simple act of putting on a hat and coat or by the way he handled a pen or a cigarette lighter. His level of appreciation for the most ordinary objects of life, the way he worked with his body, his environment—everything had presence, and because of that, everything demonstrated inherent goodness. In that way, he also taught natural hierarchy. He pointed out that the real warrior in the world understood how things are placed, used, and kept as an expression of the appreciation of basic goodness.

He asked me to help design a way to present the Shambhala wisdom in an organized manner, so that people could share this experience. He and I began a collaboration with a group of students to develop the Shambhala Training Program. When I began to consider the implications of what he was presenting, especially the fact that he put a lot of responsibility on me to present these teachings, I knew I was faced with having to grow up, to be genuine, to overcome hesitation. There was an element of fear, of wondering whether one could embrace a teaching as simple as basic goodness without reducing it to just another self-help philosophy. Having to present the Shambhala teaching, having to present ordinary wisdom over and over again and, at the same time, present it in a fresh and genuine way, was a tremendous challenge. What made me go forward was the reality of what the Dorje Dradül was manifesting, the reality of warriorship. What he was saying, he was actually doing.

The vision of a sacred world that he presented was unique, complete, and straightforward. However, it was obvious that this was no preordained plan, such as one finds in modern expositions of self-analysis, where everything is worked out and marketable. Developing the Shambhala Training Program was definitely not an easy task, but because of the self-existing wisdom of these teachings, it took shape and developed naturally, organically. Out of that process, our sense of mutual appreciation continued to deepen and grow. Although Trungpa Rinpoche was clearly presenting a challenge to us, he always exhibited the gentleness of a real warrior. He was completely patient and spacious in his attitude, trusting that we would come to our own personal understanding of warriorship. Most of all, I remember his willingness to allow us to experiment, to test our experience. He realized that we all had doubts, and he fielded all the questions that arose. He was unyielding without being intimidating, simply by the steadfastness of his conviction.

Now I have more fully come to understand and appreciate the uniqueness of the Shambhala tradition and the ordinariness of Shambhala wisdom. That wisdom becomes apparent when, in just encountering these ideas or reading this book, one hears a language which is totally new and at the same time totally familiar. The wisdom of the Shambhala teachings presented by Trungpa Rinpoche has never before been heard in this world; nevertheless, it is so familiar that it is recognizable as wisdom by people of any age or station in life. The teachings of Shambhala embody the best possible expression of human goodness that is inherent in every culture. At the same time, these ideas blend together easily with ordinary life. That is their unique quality. They are a straightforward and natural expression of the wisdom and dignity of life.

Trungpa Rinpoche left these teachings for all of us. The degree of his generosity and caring for the world was enormous. He was not only the vanguard of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition in the West, but he also reintroduced the tradition of warriorship that had been forgotten. He lived forty-seven years, seventeen of those in North America, and he accomplished so much and affected so many people in such a direct way. For ten years he presented the Shambhala teachings. In terms of time and history, that seems insignificant; however, in that short span he set in motion the powerful force of goodness that can actually change the world.

It will become more apparent in the years to come what a great effect his life had on all of us. Even at this writing, so soon after his death, the feeling of his short stay with us is penetrating and uncompromising. Those of us who carry on this tradition are compelled to do so because he showed us how to meet reality face to face, which he presented as the discipline and the path of enlightened warriorship. It is wonderful that he took time to train so many people in this discipline in order to ensure its continuity. However, this continuity still cannot be taken for granted because every moment is, as he would say,

living in the challenge,

and therefore at every moment we all renew our commitment to living.

I hope these recollections will enable readers to have some feeling of what it was like to be present at a time when something profound was brought into the consciousness of the world. Speaking for myself as the cofounder of Shambhala Training, and for those who were closely involved in the beginning of this process, we are entirely dedicated to making the teachings of the Dorje Dradül available to everyone throughout the world as much as we can, and to use all of our effort and energy and all of our life force to bring about the creation of enlightened society that we were shown. The kind of debt that I personally feel is to make sure that his vision and his teaching and the accuracy of his approach are not just perpetuated, but become part of the fabric of human culture. This is not simply the notion of trying to preserve the memory of a great man. He was not at all pretentious or concerned about such things; rather, he constantly worked for everyone’s benefit. Whether a situation was filled with tension or heavy with dullness or bubbling with passion or excitement, he always showed a clear example of how to meet the world with gentleness, humor, and fearlessness.

This is the legacy he left us. We are dedicated to that spirit and that activity—the life of the Shambhala warrior, who always gives one hundred percent, all the time. It is my wish and hope that this great teaching can spread throughout the world. Now is a time when even the most basic of human values—kindness and compassion—are lost in a sea of harshness. These teachings, more than ever, are needed to remind us of our inherent nobility. May the goodness of the Great Eastern Sun shine eternally, and may the confidence of primordial goodness awaken the hearts and minds of warriors everywhere.

T

HE

V

AJRA

R

EGENT

Ö

SEL

T

ENDZIN

Karmê Chöling

Barnet, Vermont

27 November 1987

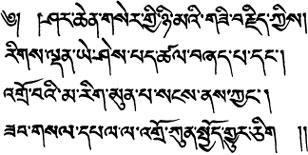

By the confidence of the Golden Sun of the Great East

May the lotus garden of the Rigdens’ wisdom bloom

May the dark ignorance of sentient beings be dispelled

May all beings enjoy profound brilliant glory

G

REAT

E

ASTERN

S

UN

The Wisdom of Shambhala

EDITED BY

C

AROLYN

R

OSE

G

IMIAN

T

O

G

ESAR OF

L

ING

T

O

G

ESAR OF

L

ING

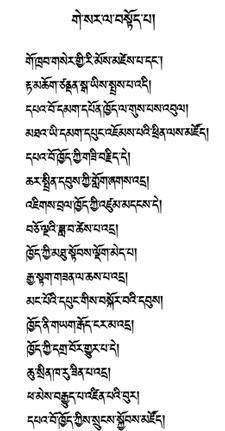

Armor ornamented with gold designs,

Great horse adorned with sandalwood saddle:

These I offer you, great Warrior General—

Subjugate now the barbarian insurgents.

Your dignity, O Warrior,

Is like lightning in rain clouds.

Your smile, O Warrior,

Is like the full moon.