The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One (45 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

The villagers told me how much it had meant to them having his monastery there to take a lead in this much-needed work of reform. At one time they had had a Tibetan monk-official as administrator of the district; later, the Chinese had also established a headquarters in this area, but had withdrawn after two years; they had made very little impression on the people. All were now very anti-Chinese and were prepared to fight for their liberty, if only with primitive bows and arrows. They had made plans to build bridges in such a way that they could be demolished at the very moment when the Chinese would be crossing them.

There was no possibility of getting any milk and, since it was winter, vegetables were in very short supply; there was nothing left for us, therefore, but to fall in with the local custom of drinking beer, of which the villagers had large quantities. This, combined with better food and rest, certainly renewed our health. When our fortnight was up we were ready to go on with our journey.

January 14

. After about four hours’ walking we came to the next village. We had already met many of the inhabitants and they had prepared accommodation for all of us. Here the houses were brighter and more cheerful and the people wore better clothes. I met a lama who had escaped from Upper Kongpo with a number of peasant refugees. His account of the Chinese persecution was the usual sad one. This party had traveled by a different route to the one we had taken.

January 15

. The next village lay farther away. Mostly we were following the Brahmaputra, but all the villages were situated on the slopes of the mountains. A bridge that we saw over the river was different from any we had yet seen; it was made of very wobbly bamboo wattle; bamboo hoops placed at intervals round it served to help the passenger to keep his balance. This village had some contact with the Indian side of the Himalayas, and consequently there were certain Indian goods to be seen, I was amused to meet men wearing pyjamas. Indian coinage was partly in circulation here and cuttings of Indian pictures from newspapers were often stuck on the walls. The specialty of this village was making a particular poison to put on their arrowheads which paralyzed the animals they hunted. The women sat on their balconies all busily engaged in spinning and weaving. The majority of the inhabitants only spoke the Mön dialect; however, some of the older ones knew Tibetan and we were welcomed and put up for the night. We were told that a detachment of Indian guards had been stationed near the village who had invited all the villagers to join in their New Year festivities on January 1, and the people had been very interested to see Indian airplanes in the vicinity.

I met the priest who was living with his family in the local temple; he could speak Tibetan and was proud of the fact that he had visited many places in Tibet. He told me that he had been in retreat and that its chief benefit had been an increase of magical power. We had an argument and I pointed out to him that Buddhism teaches that one must go beyond selfish aims: A retreat should be to increase spiritual awareness; one must start with the five moral precepts. He courteously agreed, after which we both remained silent. Yak Tulku, who had been much scandalized by the corrupt habits of these people was delighted that I had had an opportunity to expound a truly Buddhist way of life. He said that, had he been talking to this priest, he would probably have lost his temper and said something rude.

January 16

. We started on a long trek, passing several villages until we came to the last one on Tibetan territory where we camped by the riverbank. We were delighted to have water to drink and I now made it a rule that in future no beer was to be taken; I was afraid that some of the younger people were growing too fond of it.

January 17

. Our party of nineteen started out very early. It was impossible to keep close to the Brahmaputra as the bank was too rocky, so we had to walk along the mountainside above it. The top of the next pass was the boundary between Tibet and India. We were still uncertain how we would be received by the guards there. There was a big noticeboard facing us painted in the colors of the Indian flag, with large letters in Hindi saying “Bharat” and English letters saying “India.” Below, we saw a newly built stupa made of concrete and whitewashed; its presence was encouraging. The two men on guard showed their welcome as they shook hands with us though we could not speak each other’s languages. We felt intensely happy at this moment and particularly so in seeing the stupa, symbol of Buddhism, on Indian soil.

We walked down a further mile to the check post. The soldiers there confiscated Tsepa’s gun and my field glasses and in sign language indicated that we should go farther down the mountainside and not stay where we were. There were various soldiers traveling on the road and we heard an airplane overhead. Feeling tired after our long day, we camped beside a small stream. In the middle of the night a soldier came with an interpreter to see what we were up to. He merely woke us up, looked round, and went away.

January 18

. Early in the morning another soldier came to our camp and, seeing our warm fire, sat down beside it. He was smoking and offered us some of his cheroots; we accepted them because we did not like to refuse his kindness, but none of us smoked. We watched him with the greatest interest; he was so different from any Tibetan type, with his pointed nose, deep-set eyes, and mustache. Not long after a second soldier arrived; he looked more like a Tibetan and could speak our language; he said he was a Bhutanese. He had heard of Gyalwa Karmapa and told me that his party had arrived in India before the Dalai Lama left Lhasa and, to our great sorrow, he added that Khyentse Rinpoche of Dzongsar had died.

A messenger came from the army camp, which was about a quarter of a mile away, to tell us to go on to the camp where we would be looked after. When we reached it we were shown into the dak bungalow which was entirely built of bamboo and the walls were covered with basketwork. Everything was beautifully arranged with bathroom, etc., and a fully equipped kitchen. We were told that we must rest and were given rice and tinned food. We discovered that it was the adjutant of the Indian regiment stationed there who was personally looking after us; he spoke Tibetan fluently and asked for all our names. He understood that we had been abbots of important monasteries and told me that he had been privileged to meet many lamas who had come by this pass and that he himself was a Buddhist.

January 19

. In the morning the adjutant came with his senior officer. They made a list of everything that we had brought with us and asked particulars about the route that we had taken and at what date we had left our monasteries.

January 20

. The adjutant brought us temporary permits to show the Indian authorities at the airport. He explained that they had little food to spare at the camp as they were rather short themselves; but he gave us what he could and told me that we should always stay in the local dak bungalows. Before leaving he asked for my blessing.

January 21

. The road here was much better; and the bridges more strongly built with steel cables. On the way, we met an Indian official traveling on his district rounds, with no less than five porters to carry his baggage. He was very sympathetic about our having had to leave our own country and assured us that the Indian government would look after us, just as they were looking after the Dalai Lama and other Tibetan refugees. His interpreter, the headman of the local village, looked very proud of himself in his uniform. This was the country of a primitive tribe who worship nature spirits and the whole atmosphere here seemed quite different from anything we had known before, with no obvious influences either from Tibet or the Indian side. There was much greater poverty in the villages and the dak bungalow where we stopped for the night was very small. There were, however, a few people here who had worked in India among Tibetans, and I asked them to teach me a few useful Hindi words.

January 22

. We reached the town of Tuting round about midday and were shown a bamboo shelter where we could stay the night. Due to the rainy weather, here too there was a shortage of food and we were told that if we could manage on our own small supplies it would be a good thing. In the town there was a large camp of different races, all engaged on building houses for the army and the government officials in the area. There were quite a number of shops and small restaurants, and we were able to buy a few necessities, changing our Tibetan coins into Indian currency.

January 23

. No one knew how we could get to India proper, for there was a waiting list for the few airplanes flying to and fro. However, we no longer felt anxious: We were free at last and were able to wander about the town at will. I was struck by the fact that people here were much gayer and more cheerful than in the Communist-controlled Tibetan towns. As we were having our midday meal, a messenger came to tell us to go down to the airport, as there was every possibility that we would get a lift that same evening. A tractor arrived with a trailer behind it, into which we all bundled. The winding road led through a valley and we came to the gate of the airport. It was built in decorative Tibetan style, surmounted by the ashoka emblem. We disembarked and waited. No one knew of any airplanes likely to arrive that day. The evening drew in and it was quite dark. A jeep came to take me to see the local district administrator; he gave me a bag of rice and a few vegetables and apologized that supplies were so scanty and the accommodation so limited. However, he was sure that the plane would come the next day. He asked me to leave my blessing in the place, that things should go well. I thanked him and presented him with a white scarf. We spent that night in the hut.

January 24

. In the morning an official came and read out a list of our names. He told us that we would be given priority on the next plane. It arrived that morning and, since it was a transport plane, its cargo of building material was first taken off and seats screwed in afterward. There was only room for six of us: myself, my own attendant, Yak Tulku and his attendant, Tsethar, and Yönten; the rest of the party followed in a second plane that same day.

This, our first flight, was a strange new experience, skimming over cloud-covered mountains, seeing far below us the small villages and footpaths leading up to them; only by the moving shadow of the plane on the ground could we gauge how fast we were traveling.

We thought about the teaching of impermanence; this was a complete severance of all that had been Tibet and we were traveling by mechanized transport. As the moments passed, the mountain range was left behind, and the view changed to the misty space of the Indian plains stretching out in front of us.

Ugyen Tendzin had waited until he had taken the last fugitives across the Brahmaputra backwater; then he escaped himself. It had been easier for him to travel as a single man and he had followed the Brahmaputra all the way and reached India about a month later. Some of Repön’s party, including himself, succeeded in getting away from the Chinese camp and arrived in India some months later, where he is now.

A few of the refugees from Drölma Lhakhang, after crossing the backwater, managed to escape capture and they also made their way to India.

Lama Riwa’s party which had stayed at Rigong Kha and went on by the Yigong Valley were all captured by the Chinese, but escaped, reaching safety after a very difficult journey.

Nothing has been heard of Karma Tendzin, the queen of Nangchen and her party, nor of Lama Ugyen’s group of monks who went to the pilgrimage valley.

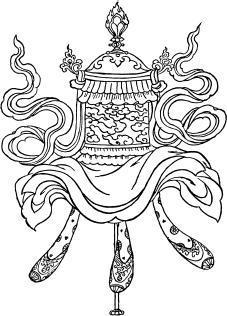

The banner of victory

.

Song of the Wanderer in Powo Valley

1

To the one greater than all the gods, beyond compare

,

O Padma Tri-me, remembering your deep kindnesses

,

Sad songs of love and irresistible devotion

,

Among the rocks and snows and lakes, well up in me

.

I see the snowy mountain reach to heaven

Pagoda-like, the clouds are its necklaces;

But when the red wind of evening scatters them

,

How sad to see its body naked and bare

.

This lake of liquid sky, the earth’s great ornament

,

The measure of the fullness of my mind—

When fish and otter fight there for their lives

,

How many drops of blood are spread upon it

.

Mortal, yet once we enjoyed the masquerade;

Now we see clearly all things perishing

.