The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 (19 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

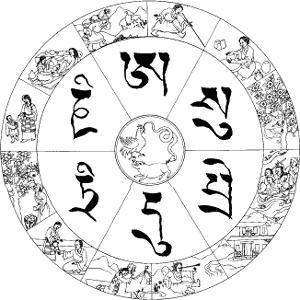

The portrait of samsara

.

DRAWING BY GLEN EDDY.

The Development of Ego

A

S WE ARE GOING

to examine the Buddhist path from beginning to end, from the beginner’s mind to the enlightened one, I think it would be best to start with something very concrete and realistic, the field we are going to cultivate. It would be foolish to study more advanced subjects before we are familiar with the starting point, the nature of ego. We have a saying in Tibet that, before the head has been cooked properly, grabbing the tongue is of no use. Any spiritual practice needs this basic understanding of the starting point, the material with which we are working.

If we do not know the material with which we are working, then our study is useless; speculations about the goal become mere fantasy. These speculations may take the form of advanced ideas and descriptions of spiritual experiences, but they only exploit the weaker aspects of human nature, our expectations and desires to see and hear something colorful, something extraordinary. If we begin our study with these dreams of extraordinary, “enlightening,” and dramatic experiences, then we will build up our expectations and preconceptions so that later, when we are actually working on the path, our minds will be occupied largely with what

will be

rather than with what

is.

It is destructive and not fair to people to play on their weaknesses, their expectations and dreams, rather than to present the realistic starting point of what they are.

It is necessary, therefore, to start on what we are and why we are searching. Generally, all religious traditions deal with this material, speaking variously of alayavijnana or original sin or the fall of man or the basis of ego. Most religions refer to this material in a somewhat pejorative way, but I do not think it is such a shocking or terrible thing. We do not have to be ashamed of what we are. As sentient beings we have wonderful backgrounds. These backgrounds may not be particularly enlightened or peaceful or intelligent. Nevertheless, we have soil good enough to cultivate; we can plant anything in it. Therefore, in dealing with this subject we are not condemning or attempting to eliminate our ego-psychology; we are purely acknowledging it, seeing it as it is. In fact, the understanding of ego is the foundation of Buddhism. So let us look at how ego develops.

Fundamentally there is just open space, the

basic ground,

what we really are. Our most fundamental state of mind, before the creation of ego, is such that there is basic openness, basic freedom, a spacious quality; and we have now and have always had this openness. Take, for example, our everyday lives and thought patterns. When we see an object, in the first instant there is a sudden perception which has no logic or conceptualization to it at all; we just perceive the thing in the open ground. Then immediately we panic and begin to rush about trying to add something to it, either trying to find a name for it or trying to find pigeonholes in which we could locate and categorize it. Gradually things develop from there.

This development does not take the shape of a solid entity. Rather, this development is illusory, the mistaken belief in a “self” or “ego.” Confused mind is inclined to view itself as a solid, ongoing thing, but it is only a collection of tendencies, events. In Buddhist terminology this collection is referred to as the five skandhas or five heaps. So perhaps we could go through the whole development of the five skandhas.

The beginning point is that there is open space, belonging to no one. There is always primordial intelligence connected with the space and openness.

Vidya,

which means “intelligence” in Sanskrit—precision, sharpness, sharpness with space, sharpness with room in which to put things, exchange things. It is like a spacious hall where there is room to dance about, where there is no danger of knocking things over or tripping over things, for there is completely open space. We

are

this space, we are

one

with it, with vidya, intelligence, and openness.

But if we are this all the time, where did the confusion come from, where has the space gone, what has happened? Nothing has happened, as a matter of fact. We just became too active in that space. Because it is spacious, it brings inspiration to dance about; but our dance became a bit too active, we began to spin more than was necessary to express the space. At this point we became

self

-conscious, conscious that “I” am dancing in the space.

At such a point, space is no longer space as such. It becomes solid. Instead of being one with the space, we feel solid space as a separate entity, as tangible. This is the first experience of duality—space and I, I am dancing in this space, and this spaciousness is a solid, separate thing. Duality means “space and I,” rather than being completely one with the space. This is the birth of “form,” of “other.”

Then a kind of blackout occurs, in the sense that we forget what we were doing. There is a sudden halt, a pause; and we turn around and “discover” solid space, as though we had never before done anything at all, as though we were not the creators of all that solidity. There is a gap. Having already created solidified space, then we are overwhelmed by it and begin to become lost in it. There is a blackout and then, suddenly, an awakening.

When we awaken, we refuse to see the space as openness, refuse to see its smooth and ventilating quality. We completely ignore it, which is called avidya.

A

means “negation,”

vidya

means “intelligence,” so it is “un-intelligence.” Because this extreme intelligence has been transformed into the perception of solid space, because this intelligence with a sharp and precise and flowing luminous quality has become static, therefore it is called avidya, “ignorance.” We deliberately ignore. We are not satisfied just to dance in the space but we want to have a partner, and so we choose the space as our partner. If you choose space as your partner in the dance, then of course you want it to dance with you. In order to possess it as a partner, you have to solidify it and ignore its flowing, open quality. This is avidya, ignorance, ignoring the intelligence. It is the culmination of the first skandha, the creation of ignorance-form.

In fact, this skandha, the skandha of ignorance-form, has three different aspects or stages which we could examine through the use of another metaphor. Suppose in the beginning there is an open plain without any mountains or trees, completely open land, a simple desert without any particular characteristics. That is how we are, what we are. We are very simple and basic. And yet there is a sun shining, a moon shining, and there will be lights and colors, the texture of the desert. There will be some feeling of the energy which plays between heaven and earth. This goes on and on.

Then, strangely, there is suddenly someone to notice all this. It is as if one of the grains of sand had stuck its neck out and begun to look around. We are that grain of sand, coming to the conclusion of our separateness. This is the “birth of ignorance” in its first stage, a kind of chemical reaction. Duality has begun.

The second stage of ignorance-form is called “the ignorance born within.” Having noticed that one is separate, then there is the feeling that one has always been so. It is an awkwardness, the instinct toward self-consciousness. It is also one’s excuse for remaining separate, an individual grain of sand. It is an aggressive type of ignorance, though not exactly aggressive in the sense of anger; it has not developed as far as that. Rather it is aggression in the sense that one feels awkward, unbalanced, and so one tries to secure one’s ground, create a shelter for oneself. It is the attitude that one is a confused and separate individual, and that is all there is to it. One has identified oneself as separate from the basic landscape of space and openness.

The third type of ignorance is “self-observing ignorance,” watching oneself. There is a sense of seeing oneself as an external object, which leads to the first notion of “other.” One is beginning to have a relationship with a so-called “external” world. This is why these three stages of ignorance constitute the skandha of form-ignorance; one is beginning to create the world of forms.

When we speak of “ignorance” we do not mean stupidity at all. In a sense, ignorance is very intelligent, but it is a completely two-way intelligence. That is to say, one purely reacts to one’s projections rather than just seeing what is. There is no situation of “letting be” at all, because one is ignoring what one is all the time. That is the basic definition of ignorance.

The next development is the setting up of a defense mechanism to protect our ignorance. This defense mechanism is feeling, the second skandha. Since we have already ignored open space, we would like next to feel the qualities of solid space in order to bring complete fulfillment to the grasping quality we are developing. Of course space does not mean just bare space, for it contains color and energy. There are tremendous, magnificent displays of color and energy, beautiful and picturesque. But we have ignored them altogether. Instead there is just a solidified version of that color; and the color becomes captured color, and the energy becomes captured energy, because we have solidified the whole space and turned it into “other.” So we begin to reach out and feel the qualities of “other.” By doing this we reassure ourselves that we exist. “If I can feel that out there, then I must be here.”

Whenever anything happens, one reaches out to feel whether the situation is seductive or threatening or neutral. Whenever there is a sudden separation, a feeling of not knowing the relationship of “that” to “this,” we tend to feel for our ground. This is the extremely efficient feeling mechanism that we begin to set up, the second skandha.

The next mechanism to further establish ego is the third skandha, perception-impulse. We begin to be fascinated by our own creation, the static colors and the static energies. We want to relate to them, and so we begin gradually to explore our creation.

In order to explore efficiently there must be a kind of switchboard system, a controller of the feeling mechanism. Feeling transmits its information to the central switchboard, which is the act of perception. According to that information, we make judgments, we react. Whether we should react for or against or indifferently is automatically determined by this bureaucracy of feeling and perception. If we feel the situation and find it threatening, then we will push it away from us. If we find it seductive, then we will draw it to us. If we find it neutral, we will be indifferent. These are the three types of impulse: hatred, desire, and stupidity. Thus perception refers to receiving information from the outside world and impulse refers to our response to that information.

The next development is the fourth skandha, concept. Perception-impulse is an automatic reaction to intuitive feeling. However, this kind of automatic reaction is not really enough of a defense to protect one’s ignorance and guarantee one’s security. In order to really protect and deceive oneself completely, properly, one needs intellect, the ability to name and categorize things. Thus we label things and events as being “good,” “bad,” “beautiful,” “ugly,” and so on, according to which impulse we find appropriate to them.

So the structure of ego is gradually becoming heavier and heavier, stronger and stronger. Up to this point, ego’s development has been purely an action and reaction process; but from now on ego gradually develops beyond the ape instinct and become more sophisticated. We begin to experience intellectual speculation, confirming or interpreting ourselves, putting ourselves into certain logical, interpretive situations. The basic nature of intellect is quite logical. Obviously there will be the tendency to work for a positive condition: to confirm our experience, to interpret weakness into strength, to fabricate a logic of security, to confirm our ignorance.

In a sense, it might be said that the primordial intelligence is operating all the time, but it is being employed by the dualistic fixation, ignorance. In the beginning stages of the development of ego this intelligence operates as the intuitive sharpness of feeling. Later it operates in the form of intellect. Actually it seems that there is no such thing as the ego at all; there is no such thing as “I am.” It is an accumulation of a lot of stuff. It is a “brilliant work of art,” a product of the intellect which says, “Let’s give it a name, let’s call it something, let’s call it ‘I am’,” which is very clever. “I” is the product of intellect, the label which unifies into one whole the disorganized and scattered development of ego.

The last stage of the development of ego is the fifth skandha, consciousness. At this level an amalgamation takes place: the intuitive intelligence of the second skandha, the energy of the third, and the intellectualization of the fourth combine to produce thoughts and emotions. Thus at the level of the fifth skandha we find the six realms as well as the uncontrollable and illogical patterns of discursive thought.