The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 (9 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

Surrendering is not a question of being low and stupid, nor of wanting to be elevated and profound. It has nothing to do with levels and evaluation. Instead, we surrender because we would like to communicate with the world “as it is.” We do not have to classify ourselves as learners or ignorant people. We know where we stand, therefore we make the gesture of surrendering, of opening, which means communication, link, direct communication with the object of our surrendering. We are not embarrassed about our rich collection of raw, rugged, beautiful, and clean qualities. We present everything to the object of our surrendering. The basic act of surrender does not involve the worship of an external power. Rather it means working together with inspiration, so that one becomes an open vessel into which knowledge can be poured.

Thus openness and surrendering are the necessary preparation for working with a spiritual friend. We acknowledge our fundamental richness rather than bemoan the imagined poverty of our being. We know we are worthy to receive the teachings, worthy of relating ourselves to the wealth of the opportunities for learning.

The Guru

C

OMING TO THE STUDY

of spirituality we are faced with the problem of our relationship with a teacher, lama, guru, whatever we call the person we suppose will give us spiritual understanding. These words, especially the term

guru,

have acquired meanings and associations in the West which are misleading and which generally add to the confusion around the issue of what it means to study with a spiritual teacher. This is not to say that people in the East understand how to relate to a guru while Westerners do not; the problem is universal. People always come to the study of spirituality with some ideas already fixed in their minds of what it is they are going to get and how to deal with the person from whom they think they will get it. The very notion that we will

get

something from a guru—happiness, peace of mind, wisdom, whatever it is we seek—is one of the most difficult preconceptions of all. So I think it would be helpful to examine the way in which some famous students dealt with the problems of how to relate to spirituality and a spiritual teacher. Perhaps these examples will have some relevance for our own individual search.

One of the most renowned Tibetan masters and also one of the main gurus of the Kagyü lineage, of which I am a member, was Marpa, student of the Indian teacher Naropa and guru to Milarepa, his most famous spiritual son. Marpa is an example of someone who was on his way to becoming a successful self-made man. He was born into a farming family, but as a youth he became ambitious and chose scholarship and the priesthood as his route to prominence. We can imagine what tremendous effort and determination it must have taken for the son of a farmer to raise himself to the position of priest in his local religious tradition. There were only a few ways for such a man to achieve any kind of position in tenth-century Tibet—as a merchant, a bandit, or especially as a priest. Joining the local clergy at that time was roughly equivalent to becoming a doctor, lawyer, and college professor, all rolled into one.

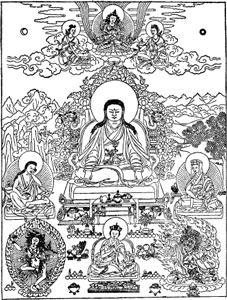

Marpa, founder of the Kagyü lineage

.

DRAWING BY SHERAB PALDEN BERU.

Marpa began by studying Tibetan, Sanskrit, several other languages, and the spoken language of India. After about three years of such study he was proficient enough to being earning money as a scholar, and with this money he financed his religious study, eventually becoming a Buddhist priest of sorts. Such a position brought with it a certain degree of local prominence, but Marpa was more ambitious and so, although he was married by now and had a family, he continued to save his earnings until he had amassed a large amount of gold.

At this point Marpa announced to his relatives his intentions to travel to India to collect more teachings. India at this time was the world center for Buddhist studies, home of Nalanda University and the greatest Buddhist sages and scholars. It was Marpa’s intention to study and collect texts unknown in Tibet, bring them home, and translate them, thus establishing himself as a great scholar-translator. The journey to India was at that time and until fairly recently a long and dangerous one, and Marpa’s family and elders tried to dissuade him from it. But he was determined and so set out accompanied by a friend and fellow scholar.

After a difficult journey of some months they crossed the Himalayas in India and proceeded to Bengal where they went their separate ways. Both men were well qualified in the study of language and religion, and so they decided to search for their own teachers, to suit their own tastes. Before parting they agreed to meet again for the journey home.

While he was traveling through Nepal, Marpa had happened to hear of the teacher Naropa, a man of enormous fame. Naropa had been abbot of Nalanda University, perhaps the greatest center for Buddhist studies the world has ever known. At the height of his career, feeling that he understood the sense but not the real meaning of the teachings, he abandoned his post and set out in search of a guru. For twelve years he endured terrific hardship at the hands of his teacher Tilopa, until finally he achieved realization. By the time Marpa heard of him, he was reputed to be one of the greatest Buddhist saints ever to have lived. Naturally Marpa set out to find him.

Eventually Marpa found Naropa living in poverty in a simple house in the forests of Bengal. He had expected to find so great a teacher living in the midst of a highly evolved religious setting of some sort, and so he was somewhat disappointed. However, he was a bit confused by the strangeness of a foreign country and willing to make some allowances, thinking that perhaps this was the way Indian teachers lived. Also, his appreciation of Naropa’s fame outweighed his disappointment, and so he gave Naropa most of his gold and asked for teachings. He explained that he was a married man, a priest, scholar, and farmer from Tibet, and that he was not willing to give up this life he had made for himself, but that he wanted to collect teachings to take back to Tibet to translate in order to earn more money. Naropa agreed to Marpa’s requests quite easily, gave Marpa instruction, and everything went smoothly.

After some time Marpa decided that he had collected enough teachings to suit his purposes and prepared to return home. He proceeded to an inn in a large town where he rejoined his traveling companion, and the two sat down to compare the results of their efforts. When his friend saw what Marpa had collected, he laughed and said, “What you have here is worthless! We already have those teachings in Tibet. You must have found something more exciting and rare. I found fantastic teachings which I received from very great masters.”

Marpa, of course, was extremely frustrated and upset, having come such a long way and with so much difficulty and expense, so he decided to return to Naropa and try once more. When he arrived at Naropa’s hut and asked for more rare and exotic and advanced teachings, to his surprise Naropa told him, “I’m sorry, but you can’t receive these teachings from me. You will have to go and receive these from someone else, a man named Kukuripa. The journey is difficult, especially so because Kukuripa lives on an island in the middle of a lake of poison. But he is the one you will have to see if you want these teachings.”

By this time Marpa was becoming desperate, so he decided to try the journey. Besides, if Kukuripa had teachings which even the great Naropa could not give him and, in addition, lived in the middle of a poisonous lake, then he must be quite an extraordinary teacher, a great mystic.

So Marpa made the journey and managed to cross the lake to the island where he began to look for Kukuripa. There he found an old Indian man living in filth in the midst of hundreds of female dogs. The situation was outlandish, to say the least, but Marpa nevertheless tried to speak to Kukuripa. All he got was gibberish. Kukuripa seemed to be speaking complete nonsense.

Now the situation was almost unbearable. Not only was Kukuripa’s speech completely unintelligible, but Marpa had to constantly be on guard against the hundreds of bitches. As soon as he was able to make a relationship with one dog, another would bark and threaten to bite him. Finally, almost beside himself, Marpa gave up altogether, gave up trying to take notes, gave up trying to receive any kind of secret doctrine. And at that point Kukuripa began to speak to him in a totally intelligible, coherent voice and the dogs stopped harassing him and Marpa received the teachings.

After Marpa had finished studying with Kukuripa, he returned once more to his original guru, Naropa. Naropa told him, “Now you must return to Tibet and teach. It isn’t enough to receive the teachings in a theoretical way. You must go through certain life experiences. Then you can come back again and study further.”

Once more Marpa met his fellow searcher and together they began the long journey back to Tibet. Marpa’s companion had also studied a great deal and both men had stacks of manuscripts and, as they proceeded, they discussed what they had learned. Soon Marpa began to feel uneasy about his friend, who seemed more and more inquisitive to discover what teachings Marpa had collected. Their conversations together seemed to turn increasingly around this subject, until finally his traveling companion decided that Marpa had obtained more valuable teachings than himself, and so he became quite jealous. As they were crossing a river in a ferry, Marpa’s colleague began to complain of being uncomfortable and crowded by all the baggage they were carrying. He shifted his position in the boat, as if to make himself more comfortable, and in so doing managed to throw all of Marpa’s manuscripts into the river. Marpa tried desperately to rescue them, but they were gone. All the texts he had gone to such lengths to collect had disappeared in an instant.

So it was with a feeling of great loss that Marpa returned to Tibet. He had many stories to tell of his travels and studies, but he had nothing solid to prove his knowledge and experience. Nevertheless, he spent several years working and teaching until, to his surprise, he began to realize that his writings would have been useless to him, even had he been able to save them. While he was in India he had only taken written notes on those parts of the teachings he had not understood. He had not written down those teachings which were part of his own experience. It was only years later that he discovered that they had actually become a part of him.

With the discovery Marpa lost all desire to profit from the teachings. He was no longer concerned with making money or achieving prestige but instead was inspired to realize enlightenment. So he collected gold dust as an offering to Naropa and once again made the journey to India. This time he went full of longing to see his guru and desire for the teachings.

However, Marpa’s next encounter with Naropa was quite different than before. Naropa seemed very cold and impersonal, almost hostile, and his first words to Marpa were, “Good to see you again. How much gold have you for my teachings?” Marpa had brought a large amount of gold but wanted to save some for his expenses and the trip home, so he opened his pack and gave Naropa only a portion of what he had. Naropa looked at the offering and said, “No, this is not enough. I need more gold than this for my teaching. Give me all your gold.” Marpa gave him a bit more and still Naropa demanded all, and this went on until finally Naropa laughed and said, “Do you think you can buy my teaching with your deception?” At this point Marpa yielded and gave Naropa all the gold he had. To his shock, Naropa picked up the bags and began flinging the gold dust in the air.

Suddenly Marpa felt extremely confused and paranoid. He could not understand what was happening. He had worked hard for the gold to buy the teaching he so wanted. Naropa had seemed to indicate that he needed the gold and would teach Marpa in return for it. Yet he was throwing it away! Then Naropa said to him, “What need have I of gold? The whole world is gold for me!”

This was a great moment of opening for Marpa. He opened and was able to receive teaching. He stayed with Naropa for a long time after that and his training was quite austere, but he did not simply listen to the teachings as before; he had to work his way through them. He had to give up everything he had, not just his material possessions, but whatever he was holding back in his mind had to go. It was a continual process of opening and surrender.

In Milarepa’s case, the situation developed quite differently. He was a peasant, much less learned and sophisticated than Marpa had been when he met Naropa, and he had committed many crimes including murder. He was miserably unhappy, yearned for enlightenment, and was willing to pay any fee that Marpa might ask. So Marpa had Milarepa pay on a very literal physical level. He had him build a series of houses for him, one after the other, and after each was completed Marpa would tell Milarepa to tear the house down and put all the stones back where he had found them, so as not to mar the landscape. Each time Marpa ordered Milarepa to dismantle a house, he would give some absurd excuse, such as having been drunk when he ordered the house built or never having ordered such a house at all. And each time Milarepa, full of longing for the teachings, would tear the house down and start again.