The Coming Plague (3 page)

Authors: Laurie Garrett

Machupo

BOLIVIAN HEMORRHAGIC FEVER

Any attempt to shape the world and modify human personality in order to create a self-chosen pattern of life involves many unknown consequences. Human destiny is bound to remain a gamble, because at some unpredictable time and in some unforeseeable manner nature will strike back.

âMirage of Health, René Dubos, 1959

Â

Â

Karl Johnson fervently hoped that if this disease didn't kill him soon somebody would shoot him and put him out of his misery. The word “agony” wasn't strong enough. He was in hell.

Karl Johnson fervently hoped that if this disease didn't kill him soon somebody would shoot him and put him out of his misery. The word “agony” wasn't strong enough. He was in hell.Every nerve ending of his skin was on full alert. He couldn't bear even the pressure of a sheet. When the nurses and doctors at Panama's Gorgas Hospital touched him or tried to draw blood samples, Johnson inwardly screamed or cried out.

He was sweating with fever, and he felt the near-paralytic exhaustion and severe pain he imagined afflicted athletes who pushed their training much too far.

When nurses on the Q ward first looked at Johnson lying beside his two colleagues they recoiled from the sight of his crimson blood-filled eyes. All over Johnson's body the tiny capillaries that acted as tributaries flowing to and from the veins' rivers of blood were leaking. Microscopic holes had appeared, out of which flowed water and blood proteins. His throat hurt so much he could barely speak or drink water, thanks to a raw and bleeding esophageal lining. Word around the hospital was that the three were victims of a strange and contagious new plague that felled them in Bolivia.

In brief moments of lucidity Johnson would ask how many days had passed. When a nurse told him it was Day Five, he groaned.

“If my immune system doesn't kick in fast, I'm a dead man,” he thought.

He'd seen it happen plenty of times in San Joaquin. Some of the people died in just four days, but most suffered over a week of this torture.

Over and over he reviewed what he had seen in that isolated village on Bolivia's eastern frontier. He hoped to think of something that could help him recover and solve the San Joaquin mystery.

It had all started exactly a year beforeâin July 1962. Johnson had just

arrived at the Middle America Research Unit (MARU) in the Panama Canal Zone, having had his fill of cataloguing respiratory viruses at the U.S. government's National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

arrived at the Middle America Research Unit (MARU) in the Panama Canal Zone, having had his fill of cataloguing respiratory viruses at the U.S. government's National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

Since 1956, then a young physician fresh from his medical training, Johnson had tediously studied viruses that caused common colds, bronchitis, and pneumonia. The work was getting plenty of praise, but Johnson, who was always impatient, was bored. When word got out that the National Institutes of Health was looking for a virologist to staff its MARU laboratory, he jumped at the chance.

Shortly after Johnson arrived in Panama, his newfound MARU colleague, Ron MacKenzie, volunteered to assist a U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) team that was heading into Bolivia to conduct nutritional surveys.

“A nutrition survey?” Johnson asked snidely.

“Well, I could use the experience, and I've never been to Bolivia. So why not?” MacKenzie said.

When MacKenzie and the DOD team met with Bolivia's Minister of Health in La Paz, the official said he had no problem authorizing their research plans, provided they first take care of a more pressing problem hundreds of miles away.

“I need an expert in mysterious diseases to investigate an epidemic in the eastern part of the country.”

All eyes turned to MacKenzie, who, as a pediatrician and trained epidemiologist, came closest to fitting the bill. He shifted uncomfortably in his chair, mumbled something about not being able to speak Spanish, and tried to imagine what eastern Bolivia might look like.

The minister went on to explain that the mysterious epidemic was fairly sizable, and two La Paz physicians had tentatively labeled it

El Typho Negro

âthe Black Typhus.

El Typho Negro

âthe Black Typhus.

The following morning found the tall, somewhat gawky MacKenzieâdressed in a black suit, starched white shirt, and wing tipsâstanding on the La Paz tarmac, a briefcase at his feet. He greeted Bolivian physician Hugo Garrón, microbiologist Luis Valverde Chinel, and a local politician, and the quartet boarded an old B-24 bomber bound for the town of Magdalena, in the country's eastern frontier region. MacKenzie looked around for a seat: there were none. The plane had been stripped down for hauling meat, and the only passengers usually on board were sides of beef.

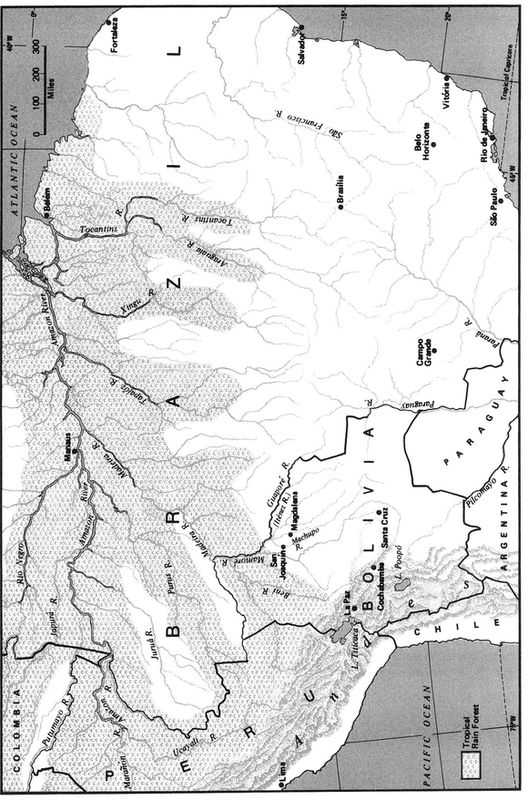

So MacKenzie stood behind the pilot, holding on to the hull for dear life during the long acceleration down the gravel runway. Because La Paz was at an elevation of 13,000 feet, planes had to reach great speeds to gain enough lift for takeoff. After what seemed an extraordinary amount of time, the Bolivian Indian mechanic who was squatting between the pilot and the copilot pulled a lever in the cockpit floor, withdrawing the landing gear, and they took off.

Like a tired old condor, the bomber circled La Paz slowly several times, spiraling upward to 16,000 feet, high enough to fly into a narrow pass

between the Andean peaks that towered around La Paz. MacKenzie found himself staring aghast at avalanches of ice cascading off dangerously close cliffs.

between the Andean peaks that towered around La Paz. MacKenzie found himself staring aghast at avalanches of ice cascading off dangerously close cliffs.

Â

AMAZONIA

When the plane escaped the claustrophobic mountain pass, it was enveloped in a dense fog which forced the pilots to fly by instruments alone: a magnetic compass, stopwatch, map, and notepad.

MacKenzie figured this was already enough adventure. Just three years ago he had been patching broken bones and vaccinating kids in a bucolic town north of San Francisco. This new exploit was a bit more perilous than anything he had gambled on when he left private practice to go into public health.

As the plane descended into the fog, MacKenzie began to feel the heat and humidity increase, sweat built under his stiffly starched shirt, and when the fog cover broke, he watched seemingly endless grassy savannas pass beneath them. These were broken up by outcroppings of low, tree-covered alturas hills, and by long winding rivers lined with thin bandas strips of rain forest.

“It looks just like Florida,” MacKenzie thought. “Kind of like the Everglades.”

After two more long hours the plane landed in the little town of Magdalena, and MacKenzie couldn't believe his eyes.

“My gosh,” he exclaimed, “there must be two hundred people out there, standing around the plane.” The women in the throng were dressed entirely in mourning; the men wore black armbands. The bereaved people of Magdalena had gathered to greet “the experts” who had come to end their epidemic.

“Experts?” MacKenzie muttered, casting an uncomfortable glance at Valverde and Garrón. “Well, I'm it.”

With the grim entourage around them, the group dodged lumbering oxcarts as it made its way past a scattering of thatch-roofed adobe houses to the town plaza, a large courtyard surrounded by a circular arcade and the homes and stores of Magdalena. A sad, lethargic feeling pervaded everything.

At Magdalena's tiny clinic MacKenzie found a dozen patients writhing in pain.

“My God!” he exclaimed as he watched one after another vomit blood. MacKenzie shuddered, feeling the tremendous onus of his position and cursing the naivete with which he had walked into the situation. It seemed that only yesterday he was doling out antibiotics in a clinic in Sausalito to kids whose frolicking was briefly interrupted by sore throats. What MacKenzie saw on the ward forced him to push aside his pediatrics training and, for the moment, draw upon the lessons in courage and horror he had learned during World War II combat.

He was told that most of the sick were outsiders from Orobayaya. The

mere name of that distant village sent shivers through the Magdalenistas, who spoke of it with unconcealed fear.

mere name of that distant village sent shivers through the Magdalenistas, who spoke of it with unconcealed fear.

Soon the lanky MacKenzie, who towered over the Bolivians, was crouched in a dugout canoe making its way by moonlight upriver toward the plagued village. As they glided along MacKenzie kept spotting enormous “logs”âfar larger than their canoeâsliding down the riverbanks toward them. The hair on the back of his neck stood up when he realized the “logs” were alligators.

The next day the group rode forty kilometers on horseback to Orobayaya.

It was deserted. The six hundred residents had fled days earlier in panic, leaving the village to pigs and chickens that scampered madly about in search of food.

MacKenzie returned to Magdalena, collected some blood samples from local patients, and headed back to Panama, where he tried to convince MARU director Henry Beye and the NIH bosses in Bethesda that the Bolivian situation warranted further investigation.

“It's probably just the flu,” was the consensus from NIH officials.

“It's something strange and dangerous,” MacKenzie insisted.

Both MacKenzie and Johnson thought the Bolivian villagers' symptoms resembled those brought on by a recently discovered Latin American virus, found near the Junin River in 1953 in Argentina. The Argentine virus was a close cousin of Tacaribe, which caused a disease of bats and rodents in Trinidad, also only recently discovered. While there was no evidence that Tacaribe could infect human beings, Junin was clearly lethal in many cases. In sparsely populated agricultural areas of Argentina's vast pampas, Junin appeared as if out of nowhere among men working the corn harvests. It too was a human killer that disrupted capillaries, causing people to bleed to death. Nobody was sure how the Argentines got Junin; there was speculation the virus might be airborne.

No point in taking stupid chances, Johnson thought. Though the NIH had not approved a MARU investigation of the epidemic, he flew to the U.S. Army's Fort Detrick, in Maryland, to see Al Wieden. A pioneer in laboratory safety, Wieden had turned Fort Detrick into the world's premier center of research on deadly microbes. Johnson wanted something unheard of: a portable box of some sort so he could safely study Junin in the fieldâor whatever was wiping out the people of San Joaquin.

At Fort Detrick there was a lot of research underway on “germ-free mice”âanimals that had such weak immune systems that virtually any microbe could prove lethal to the mutant rodents. To keep the mice alive, scientists housed them inside airtight boxes that were constantly under positive pressure, pushing air past special filters to the mice, and then out again, toward the scientists. In this way, the mice breathed only sterile air. Scientists worked with the mice by inserting their hands into airtight rubber gloves that were built into the sides of the pressure box. The “glove

boxes,” as the steel contraptions were called, were about the size of large coffins and weighed hundreds of pounds.

boxes,” as the steel contraptions were called, were about the size of large coffins and weighed hundreds of pounds.

Johnson's idea was to convert one of these contraptions from positive to negative pressure so that all air would go inward, toward samples of possibly dangerous animals or microbes. That way, he could work relatively safely in a portable laboratory.

Such a portable laboratory had never before been used, and Wieden wasn't sure how to jury-rig the positive-pressure boxes. But, racing against time, Johnson and Wieden found a new, lighter-weight plastic glove box and surrounded it with a vast rib cage of aluminum poles to prevent the container from imploding when the pressure reversed from inside-out to outside-in. To their mutual delight, it worked.

Other books

Border of a Dream: Selected Poems of Antonio Machado (Spanish Edition) by Antonio Machado

The Great Christmas Bowl by Susan May Warren

Daisies In The Wind by Jill Gregory

Crimson Falls (The Depravity Chronicles) by Grove, Joshua

England or Bust by Georgiana Louis

We Interrupt This Date by L.C. Evans

Kwaito Love by Lauri Kubbuitsile

A Wedding by Dawn by Alison Delaine

Hide Yourself Away by Mary Jane Clark

The Black Chapel by Marilyn Cruise