The Coming Plague (47 page)

Authors: Laurie Garrett

Like Jaffe, Francis, and Osborn, Curran recognized that something unique was occurring among gay male residents of some cities with large homosexual populations. He tried to warn the physicians Michael Callen called “the clap doctors,” their patients, and gay organizations. But everybody was enjoying the party too much. Besides, after so many decades of

maltreatment by every imaginable government agency and medical organization, including officially being labeled mentally ill during the 1950s by the American Psychiatric Association, gay men weren't about to let another bureaucrat tell them to slow down.

maltreatment by every imaginable government agency and medical organization, including officially being labeled mentally ill during the 1950s by the American Psychiatric Association, gay men weren't about to let another bureaucrat tell them to slow down.

By 1980 thirty-year-old Greggory Howard had been carrying a heroin addiction for thirteen years. Cut off from his family, Howard was a member of a community of heroin addicts who lived amidst the extraordinary squalor of Newark's burned-out tenements.

It was shortly after the 1967 riots that Greggory Howard, then a high school junior, first shot heroin into his veins. His warm personality and good grades held promise that he might escape New Jersey's notorious slum to a better life.

“Life was good to Greggory,” Howard said, always referring to himself in the third person. “Yes, it was. It really was. My parents did everything right, they were very good to me. But Greggory just had ⦠just had to drift away.”

In 1967 racial tensions in the United States were as high as anyone could remember. The civil rights movement had passed from polite sit-down demonstrations and peaceful marches to unfettered rage when its leaders shifted their foci from the Deep South to the industrialized North. By the mid-1960s racial tensions had reached a tinderbox level.

Newark ignited in 1967; block after block went up in flames amid riots between residents of the city's slums and the police and National Guard. Tanks patrolled the streets.

Frightened, Greggory stayed out of the fray, but it left him with a sense of tragedy and hopelessness. Afterward, he took to walking along Prince Street and Hamilton, staring at the charred structures that had once housed his friends, teachers, and relatives, and he tried heroin for the first time. One of his ex-girlfriends was already shooting up, and she seemed to like getting high. Why not try?

Now it was 1980. Howard's nose was broken, a nasty scar zigzagged across his left cheek, and he walked with a jerk, all thanks to beatings by dealers, crooks, and hoodlums. Those veins that hadn't disappeared were on the verge of collapse or embolism from the thousands of needles he'd jammed into his arms, neck, and thighs. Howard's liver was shot, because of hepatitis.

To avoid being arrested for carrying drug paraphernalia

43

Howard rarely had on his person either heroin or the gearâthe cooker, tourniquet, syringe, and needlesâthat was needed to prepare and inject the drug. Like most street-savvy addicts, Howard always had on hand a supply of minor street drugs, possession of which did not constitute a major crime: Valium, marijuana, a variety of “downers” that could help him stay relatively steady between heroin highs. And when he had the cash, Howard went to dealers at any of a number of apartments, abandoned buildings, alleys, parked cars, or parks and shot up, using works supplied by the dealer or another junkie.

43

Howard rarely had on his person either heroin or the gearâthe cooker, tourniquet, syringe, and needlesâthat was needed to prepare and inject the drug. Like most street-savvy addicts, Howard always had on hand a supply of minor street drugs, possession of which did not constitute a major crime: Valium, marijuana, a variety of “downers” that could help him stay relatively steady between heroin highs. And when he had the cash, Howard went to dealers at any of a number of apartments, abandoned buildings, alleys, parked cars, or parks and shot up, using works supplied by the dealer or another junkie.

Â

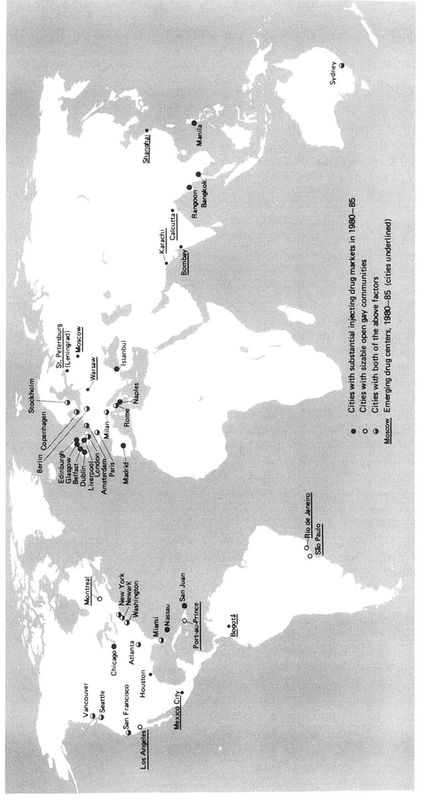

KEY GAY COMMUNITIES AND CENTERS

OF INJECTING DRUG USE, 1980s

OF INJECTING DRUG USE, 1980s

“Someday I'm going to detox my ass,” Howard would say, staring off on a high at Newark's hundreds of empty lotsâthe legacy of 1967.

Heroin, cocaine, amphetamines, and the host of other drugs easily purchased in the full glare of sunlight in most large American and European cities hadn't always been public health disasters. But they clearly did pose a crisis for urban health by 1980âan opportunity, a new ecology, for the microbes.

The anonymity of cities provided cover for illegal activity. The density of the population offered a steady flow of consumers, even for self-destructive products. And the alienation ensured that there would always be people willing to trade their health, wealth, and esteem for something that would take their minds to another place, be it alcohol, Valium, or heroin.

Once it reached Newark, a two-pound bag of pure heroin might be “cut” or “stepped on” with some other chemical by 90 or 95 percent, giving the wholesaler nearly 200 pounds (90 kilos) of street-quality heroin to sell to a retailer. The retailer might further cut the drug to increase his profit potential, so that Greggory Howard's daily high might be on a solution ranging from 2 to 15 percent heroin. In 1974, by the time it reached Newark, one acre's opium could yield more than $40 million.

44

44

Profits in the opium/morphine/heroin network were greatest when the risks of police interdiction or interference from competitors was low. Large cities with slums afforded ideal environments, particularly if they were near ports or international airports. If hefty sales could be maintained in the crime-ridden inner-city areas there was no need to risk law enforcement's attention in small towns or tight-knit suburban communities. In slum neighborhoods where most people were hostile to the police, retailers could operate with near-impunity. If kids in the suburbs wanted heroinâand by 1980 many of them very much didâthey could come into the city to obtain supplies.

45

45

Despite expenditures of billions of federal law enforcement dollars since 1969, when the U.S. Congress voted for a “full-scale attack” on the heroin problem, the number of heroin addicts in the United States would rise from 55,000 in 1955 to 1.5 million in 1987 and they could be found, regardless of race, in any community that offered a steady supply of the drug.

46

In Greggory Howard's state, New Jersey, by 1980 heroin users were of all races, ages, and economic backgrounds, though the majority were white men between twenty-five and thirty-five years of age. About 40 percent of the state's heroin users were holding down jobs. Most had sought treatment several timesâand failed several times.

47

46

In Greggory Howard's state, New Jersey, by 1980 heroin users were of all races, ages, and economic backgrounds, though the majority were white men between twenty-five and thirty-five years of age. About 40 percent of the state's heroin users were holding down jobs. Most had sought treatment several timesâand failed several times.

47

The urban heroin environment was ideal for dozens of different microbes. The drug user generally had an impaired immune system due to the narcotics' effects, to the constant injection of other people's blood cells carried on shared syringes, and to the numerous compounds used to cut the product. On the one hand, they had overexcited antibody responses provoked by all the immune system stimulators, such as other people's cells. Many therefore tested positive for rheumatoid factor and other markers of a system so overstimulated that it might be producing antibodies against itself. This autoimmunity could lead to the body's inability to distinguish genuine microbial threats from vital human cells.

48

48

On the other hand, the large phagocytic cells of the immune systems of injecting drug users, which usually bore the responsibility of ingesting and destroying bacteria and other invaders, were alarmingly nonresponsive. And the T-cell system, comprised of cells that usually tipped the rest of the immune system off to the presence of potential threats, was seriously dysfunctional, in part because some lymphocytes bore receptors for opiates, and were dampened directly by heroin.

49

49

As a result, microbes found the environment of the body of a heroin user far less hostile than that presented by healthy

Homo sapiens.

Homo sapiens.

The drug user's basic lifestyle also offered unique opportunities for microbial passage from human to human. Most of the addicts shared one another's injecting equipment. When an addict injected heroin, or any other drug, some of his or her blood might be pulled into the syringe when the equipment was drawn from the vein and the plunger reset. If the injector was infected with, for example,

Staphylococcus

bacteria, the microbes would be withdrawn into the syringe as well.

Staphylococcus

bacteria, the microbes would be withdrawn into the syringe as well.

All the staph bacteria then required was the genetically acquired ability to withstand whatever environment the syringe rested in when not in use. That might mean a few hours hidden outdoors on a subzero Newark nightâconditions too tough for most organisms. On a hot, humid August night lying in a watery “cleaning dish,” however, the microbes found a highly favorable ecology. The least challenging situation was the shooting gallery, where one person immediately passed his contaminated syringe to another.

Needles also helped microbes bypass the multitudinous barriers humans had in their skin, nostrils, and lungs, and go directly to the bloodstream. Even organisms with weak “delivery systems,” as Bernard Fields called them, could thrive in the heroin ecology.

Finally, many heroin addicts lived in acute squalor, ate poorly, worked as prostitutes for drug money, and used a broad range of additional intoxicants, each of which uniquely altered the

Homo sapiens

ecology in ways the microbes might find advantageous.

Homo sapiens

ecology in ways the microbes might find advantageous.

In 1929 malaria caused by

Plasmodium falciparum

broke out in downtown Cairo, Egypt, due to needle sharing by local drug addicts. By the late 1930s a similar heroin-driven malaria epidemic was spreading through

New York City, reaching such high levels among drug addicts that it was considered endemic. Six percent of New York City jail inmates at the time had signs of malaria infectionâall of them injecting drug users. One hundred and thirty-six New Yorkers died of malaria during the periodânone of them had been bitten by mosquitoes.

50

The epidemic stopped when the heroin retailers, concerned about losing their customers, started adding quinine to their cut heroin.

Plasmodium falciparum

broke out in downtown Cairo, Egypt, due to needle sharing by local drug addicts. By the late 1930s a similar heroin-driven malaria epidemic was spreading through

New York City, reaching such high levels among drug addicts that it was considered endemic. Six percent of New York City jail inmates at the time had signs of malaria infectionâall of them injecting drug users. One hundred and thirty-six New Yorkers died of malaria during the periodânone of them had been bitten by mosquitoes.

50

The epidemic stopped when the heroin retailers, concerned about losing their customers, started adding quinine to their cut heroin.

Such dealer “benevolence” was more than offset, however, by routine contamination of heroin products, the result of poor chemical processing or the use of microbe-supporting substances to dilute the drug.

51

51

Numerous types of microbes managed to successfully exploit the heroin ecology. For example, between 1969 and 1974 physicians at San Francisco General Hospital noticed an increase in endocarditisâlifeâthreatening infections of the heart. In seventeen of the nineteen cases, the individuals were drug addicts. And the organism responsible was the

Serratia marcescens

bacterium. Despite vigorous antibiotic treatment, 68 percent died. Searches of hospital records as far back as 1963 revealed no prior case of

S. marcescens

-induced endocarditis in San Francisco, proving it was a newly emergent microbial threat.

52

Serratia marcescens

bacterium. Despite vigorous antibiotic treatment, 68 percent died. Searches of hospital records as far back as 1963 revealed no prior case of

S. marcescens

-induced endocarditis in San Francisco, proving it was a newly emergent microbial threat.

52

Endocarditis was increasingly a problem worldwide in heroin-plagued cities. Bacteria and fungi entered the bloodstream on dirty needles and colonized the heart valves and other components of the vital organs. In most cases, antibiotic therapy proved fruitless. Prior to 1976 New York City experienced such endocarditis outbreaks among drug addicts, caused by

Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Candida

, and

Pseudomonas

. Chicago, Helsinki, Seattle, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and Detroit also witnessed outbreaks driven by those organisms, as well as

S. marcescens

.

Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Candida

, and

Pseudomonas

. Chicago, Helsinki, Seattle, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and Detroit also witnessed outbreaks driven by those organisms, as well as

S. marcescens

.

Bacterial and fungal infections of all sorts became so prevalent among drug injectors by the mid-1970s that many began to prophylactically medicate themselves with antibiotics. An antibiotics black market, operating in tandem with the heroin trade, developed in many cities in Europe, Asia, and the United States, servicing heroin users with a variety of antimicrobials. But their use of these medicinal drugs was counterproductive, because the black market's supplies were sporadic and rarely offered consistent varieties of antibiotics.

Drug addicts, therefore, became ideal breeding grounds for antibiotic-resistant organisms. From a public health perspective the problem was restricted to the drug users themselves, who in increasing numbers throughout the 1970s suffered and died from antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

But in 1982 injecting drug users in Boston and Detroit were taking black-market methicillin whenever they could to prevent bacterial infections. Strains of the bacteria emerged that possessed two different types of transferable methicillin-resistance genes.

53

When the infected heroin users were hospitalized, a new resistant

Staphylococcus

, dubbed MRSA, spread to the medical staff and other patients.

53

When the infected heroin users were hospitalized, a new resistant

Staphylococcus

, dubbed MRSA, spread to the medical staff and other patients.

Tuberculosis also lurked in the heroin ecology. Health authorities in most industrialized countries thought the TB scourge of the pre-antibiotic era was licked, and in absolute numbers of active cases in humans it certainly had declined dramatically by the 1970s. But in New York City hospitals in 1979, Dr. Lee Reichman spotted a trend that had gone unnoticed: TB cases in the city's poor, black neighborhood of Harlem were appearing at a rate of 406.6 per 100,000 residents who eschewed injectable drugs. But among the addicted residents of Harlem an astonishing 3,740 per 100,000 had active tuberculosis.

54

54

It seemed reasonable to hypothesize as early as 1979 that TB was spreading among members of the heroin-addicted populations of the wealthy nations, even as the disease was disappearing from their general populations. It might have warranted concern that decades of TB control efforts might be defeated if a subpopulation of actively infected individuals was left alone.

Other books

Fierce Enchantment by Carrie Ann Ryan

Turbulence by Elaina John

Submission by Michel Houellebecq

Kiss Lonely Goodbye by Lynn Emery

Drought by Pam Bachorz

Orphan Brigade by Henry V. O'Neil

True Treasure: Real - Life History Mystery by Lisa Grace

White Heat by Pamela Kent

Gargoyles by Bill Gaston