The Complete Essays (76 page)

Read The Complete Essays Online

Authors: Michel de Montaigne

Tags: #Essays, #Philosophy, #Literary Collections, #History & Surveys, #General

[A] Let us confess the truth: pick out, even from the lawful, moderate army,

20

those who are fighting simply out of zeal for their religious convictions; then add those who are concerned only to uphold the laws of their country and to serve their King: you would not have enough to form one full company of fighting men. How does it happen that so few can be found who maintain a consistent will and action in our civil disturbances? How does it happen that you can see them sometimes merely ambling along, sometimes charging headlong – the very same men sometimes ruining our affairs by their violence and harshness and at other times by their lukewarmness, their softness and their sloth? It must be that they have been motivated by private concerns, [C] by ones due to chance; [A] as these change, so do they.

[C] It is evident to me that we only willingly carry out those religious duties which flatter our passions. Christians excel at hating enemies. Our zeal works wonders when it strengthens our tendency towards hatred, enmity, ambition, avarice, evil-speaking… and rebellion. On the other hand, zeal never makes anyone go flying towards goodness, kindness or temperance, unless he is miraculously pre-disposed to them by some rare complexion. Our religion was made to root out vices: now it cloaks them, nurses them, stimulates them.

[A] There is a saying: ‘Do not try to palm off sheaves of straw on God.’ If we believed in God – I do not mean by faith but merely with bare credence, indeed (and I say it to our great shame) if we believed him and knew him just as we believe historical events or one of our companions, then we would love him above all other things, on account of the infinite goodness and beauty shining within him: at the very least he would march equal in the ranks of our affections with riches, pleasure, glory and

friends.

21

[C] The best among us does not fear to offend him as much as offending neighbour, kinsman, master. On this side there is the object of one of our vicious pleasures: on the other, the glorious state of immortality, equally known and equally convincing – is there anyone so simple-minded as to barter one for the other? And yet we often give it up altogether, out of pure contempt; for what attracts us to blasphemy except, perhaps, the taste of the offence itself?

Antisthenes, the philosopher, was being initiated into the Orphic mysteries; the priest said that those who make their religious profession would receive after death joys, perfect and everlasting. He replied: ‘Why do you not die yourself then?’ Diogenes’ retort was more brusque (that was his fashion) and rather off our subject: when the priest was preaching at him to join his order so as to obtain the blessings of the world to come, he replied: ‘Are you asking me to believe that great men like Agesilaus and Epaminondas will be wretched, whilst a calf like you will be happy, just because you are a priest?’

22

[A] If we were to accept the great promises of everlasting blessedness as having the same authority as a philosophical argument, no more, we would not hold death in such horror as we do:

[B]

Non jam se moriens dissolvi conquereretur;

Sed magis ire foras, vestemque relinquere, ut anguis,

Gauderet, praelonga senex aut cornua cervus

.

[The dying man would not then complain that he is being ‘loosened asunder’, but would, rather, rejoice to be ‘going outside’, like a snake casting off its skin, or an old stag casting off his over-long antlers.]

23

[A] ‘I wish to be loosened asunder’, he would say, ‘and to be with Jesus Christ.’ The force of Plato’s dialogue on the immortality of the soul led some of his disciples to kill themselves, the sooner to enjoy the hopes which he gave them.

24

All this is a clear sign that we accept our religion only as we would fashion it, only from our own hands – no differently from the way other religions gain acceptance. We happen to be born in a country where it is practised, or else we have regard for its age or for the authority of the men who have upheld it; perhaps we fear the threats which it attaches to the wicked or go along with its promises. Such considerations as these must be deployed in defence of our beliefs, but only as support-troops. Their bonds are human. Another region, other witnesses, similar promises or similar menaces, would, in the same way, stamp a contrary belief on us. [B] We are Christians by the same title that we are Périgordians or Germans.

[A] Plato said few men are so firm in their atheism that a pressing danger does not bring them to acknowledge divine power;

25

such behaviour has nothing to do with a true Christian; only mortal, human religions become accepted by human procedures. What sort of faith must it be that is planted by cowardice and established in us by feebleness of heart! [C] What an agreeable faith, which believes what it believes, because it is not brave enough to disbelieve it! [A] How can vicious passions, such as inconstancy and sudden dismay, produce in our souls anything right?

[C] Plato says that people first decide, by reasoned judgement, that what is told about hell and future punishment is just fiction. But when they have the opportunity really to find out, by experience, when old age or illness brings them close to death, then the terror of it fills them with belief again, out of horror for what awaits them.

To impress such ideas upon people is to make them timorous of heart: that is why Plato in his

Laws

forbids any teaching of threats such as these or of any conviction that ill can come to Man from the gods. (When it does happen, it is for man’s greater good or like a medical purgation.)

26

They tell that Bion, infected by the atheistic teachings of Theodorus, used to mock religious men; but eventually, when death approached, he gave himself over to the most extreme superstitions, as though the gods took themselves off and brought themselves back according to the needs of Bion.

27

Plato – and these examples – lead to the conclusion that either love or

force can bring us back to a belief in God. Atheism, as a proposition, is a monstrous thing, stripped, as it were, of natural qualities. It is awkward and difficult to fix it firmly in the human spirit, however impudent or however unruly. We have seen plenty of people who are egged on by vanity and pride to conceive lofty opinions for setting the world to rights; to put themselves in countenance they affect to profess atheism: but even if they are mad enough to try and plant it in their consciousness, they are not strong enough to do so. Give them a good thrust through the breast with your sword and they never fail to raise clasped hands to heaven. And when fear or sickness has cooled down the licentious fever-heat of that transient humour, they never fail to come back to themselves again, letting themselves be reconciled to recognized standards and beliefs. Seriously digested doctrine is one thing: these surface impressions are quite another. They are born of a mind unhinged, in the spirit of debauchery; they drift rashly and erratically about in the fancies of men. What wretched, brainless men they are, trying to be worse than they can be!

[A] That great soul [C] of Plato [A] – great, however, with merely human greatness – was led into a neighbouring mistake by the error of paganism and his ignorance of our holy Truth: he held that it is children and old men who are most susceptible to religion, as if religion were born of human weakness and drew her credibility from it.

28

[A] The knot which ought to attach our judgement and our will and to clasp our souls firmly to our Creator should not be one tied together with human considerations and strengthened by emotions: it should be drawn tight in a clasp both divine and supernatural, and have only one form, one face, one lustre; namely, the authority of God and his grace.

But, once our hearts and souls are governed by Faith, it is reasonable that she should further her purposes by drawing upon all of our other parts, according to their several capacities. Moreover, it is simply not believable that there should be no prints whatsoever impressed upon the fabric of this world by the hand of the great Architect, or that there should not be at least some image within created things relating to the Workman who made them and fashioned them. He has left within these lofty works the impress of his Godhead: only our weakness stops us from discovering it. He tells us himself that he makes manifest his unseen workings through those things which are seen. Sebond toiled at this honourable endeavour, showing

us that there is no piece within this world which belies its Maker. God’s goodness would be put in the wrong if the universe were not compatible with our beliefs. All things, Heaven, Earth, the elements, our bodies and our souls are in one accord: we simply have to find how to use them. If we have the capacity to understand, they will teach us. [B] For this world is a most holy Temple into which Man has been brought in order to contemplate the Sun, the heavenly bodies, the waters and the dry land – objects not sculpted by mortal hands but made manifest to our senses by the Divine Mind in order to represent intelligibles. [A] “The invisible things of God’, says St Paul, ‘are clearly seen from the creation of the world, his Eternal Wisdom and his Godhead being perceived from the things he has made.’

29

Atque adeo faciem coeli non invidet orbi

Ipse Deus, vultusque suos corpusque recludit

Semper volvendo; seque ipsum inculcat et offert,

Ut bene cognosci possit, doceatque videndo

Qualis eat, doceatque suas attendere leges

.

[God himself does not begrudge to the world the sight of the face of heaven, which, ever-rolling, unveils his countenance, his incorporate being inculcating and offering himself to us, so that he may be known full well; he teaches the man who contemplates to recognize his state, teaches him, also, to wait upon his laws.]

30

Our human reasonings and concepts are like matter, heavy and barren: God’s grace is their form, giving them shape and worth. The virtuous actions of Socrates and of Cato remain vain and useless, since they did not have, as their end or their aim, love of the true Creator of all things nor obedience to him: they did not know God; the same applies to our concepts and thoughts: they have a body of sorts, but it is a formless mass, unenlightened and without shape, unless accompanied by faith in God and by grace. When Faith tinges the themes of Sebond and throws her light

upon them, she makes them firm and solid. They then have the capacity of serving as a finger-post, as an elementary guide setting an apprentice on the road leading to knowledge such as this; they fashion him somewhat into shape and make him capable of God’s grace, which then furnishes out our belief and perfects it.

I know a man of authority, a cultured, educated man, who admitted to me that he had been led back from the errors of disbelief by means of the arguments of Sebond. Even if you were to strip them of their ornaments and of the help and approbation of Faith – even if you were to take them for purely human notions – you would find, when it comes to fighting those who have plunged down into the dreadful, horrible darkness of irreligion, that they still remain more solid and more firm than any others of the same kind which you can set up against them. We rightly can say to our opponents,

‘Si melius quid habes, accerse, vel imperium fer’

[If you have anything better, produce it, or submit]:

31

let them allow the force of our proofs or else show us others, elsewhere, on another subject, as closely woven or of better stuff.

Without thinking I have already half-slipped into the second of the charges which I set out to counter on behalf of Sebond.

Some say that his arguments are weak and unsuited to what he wants to demonstrate; they set out to batter them down with ease. People like those need to be shaken rather more roughly, since they are more dangerous than the first and more malicious. [C] We are only too willing to couch other men’s writings in senses which favour our settled opinions: an atheist prides himself on bringing all authors into accord with atheism, poisoning harmless matter with his own venom.

32

[A] Such people have some mental prepossession which makes Sebond’s reasons seem insipid. Moreover it seems to them that they have been allowed an easy game, with freedom to fight against our religion with purely human weapons: they would never dare to attack her in the full majesty of her imperious authority. The means I use and which seem more fitted to abating such a frenzy is to trample down human pride and arrogance, crushing them under our feet; I make men feel the emptiness, the vanity, the nothingness of Man, wrenching

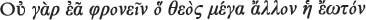

from their grasp the sickly arms of human reason, making them bow their heads and bite the dust before the authority and awe of the Divine Majesty, to whom alone belong knowledge and wisdom; who alone can esteem himself in any way, and from whom we steal whatever worth or value we pride ourselves on: [God permits no one to esteem himself higher].

[God permits no one to esteem himself higher].

33