The Complete Essays (86 page)

Read The Complete Essays Online

Authors: Michel de Montaigne

Tags: #Essays, #Philosophy, #Literary Collections, #History & Surveys, #General

[A]

Vivere si recte nescis, decede peritis;

Lusisti satis, edisti satis atque bibisti;

Tempus abire tibi est, ne potum largius aequo

Rideat et pulset lasciva decentius aetas

.

[If you do not know how to live as you should, give way to those who do. You have played enough in bed; you have eaten enough, drunk enough: it is time to be off, lest you start to drink too much and find that pretty girls rightly laugh at you and push you away.]

But what does this consensus amount to, if not to a confession of powerlessness on the part of Philosophy? She sends us for protection not merely to ignorance but to insensibility, to a total lack of sensation, to non-being.

Democritum postquam matura vetustas

Admonuit memorem motus languescere mentis,

Sponte sua leto caput obvius obtulit ipse

.

[When mature old age warned Democritus that he was losing his memory and his mental faculties, he spontaneously offered his head to Destiny.]

As Antisthenes said: We need a store of intelligence, to understand; failing that, a hangman’s rope. In this connection Chrysippus used to quote from Tyrtaeus the poet:

‘Draw near to virtue… or to death.’

[C] Crates used to say that love was cured by time or hunger; those who like neither can use the rope. [B] Sextius – the one whom Seneca and Plutarch talk so highly of – gave up everything and threw himself into the study of philosophy; he found his progress too long and too slow, so he decided to drown himself in the sea. In default of learning, he ran to death.

Philosophy lays down the law on this subject in these words: If some great evil should chance upon you – one you cannot remedy – then a haven is always near: swim out of your body as from a leaky boat; only a fool is bound to his body, not by love of life but by fear of death.

134

[A] Just as life is made more pleasant by simplicity, it is also made better and more innocent (as I was about to say earlier on). According to St Paul, it is the simple and the ignorant who rise up and take hold of heaven, whereas we, with all our learning, plunge down into the bottomless pit of hell.

135

I will not linger here over two Roman Emperors, Valentian – a sworn enemy of knowledge and scholarship – and Licinius, who called them a poison and a plague within the body politic;

136

nor over Mahomet who, [C] I am told, [A] forbade his followers to study. What we must do is to attach great weight to the authoritative example of a great man, Lycurgus, as well as to the respect we owe to Sparta, a venerable, great and awe-inspiring form of government, where letters were not taught or practised but where virtue and happiness long flourished. Those who come back from the New World discovered by the Spaniards in the time of our fathers can testify how those peoples, without magistrates or laws, live lives more Ordinate and more just than any we find in our own countries, where there are more laws and legal officials than there are deeds or inhabitants.

Di cittatorie piene e di libelli,

D’esamine e di carte, di procure,

Hanno le mani e il seno, e gran fastelli

Di chiose, di consigli e di letture:

Per cui le faculta de poverelli

Non sono mai ne le citta sicure;

Hanno dietro e dinanzi, e d’ambi ilati,

Notai procuratori e advocati

.

[Their hands and their law-bags are full of summonses, libels, inquests, documents and powers-of-attorney; they have great folders full of glosses, counsels’ opinions and statements. For all that, the poor are never safe in their cities but are surrounded, in front, behind and on both sides, by procurators and lawyers.]

137

A later Roman senator meant much the same when he said that the breath of their forebears stank of garlic but inwardly they smelt of the musk of a good conscience; men of his time, on the contrary, were doused in perfume yet inwardly stank of every sort of vice.

138

In other words he agrees with

me: they had ample learning and ability but were very short of integrity. Lack of refinement, ignorance, simplicity and roughness go easily with innocence, whereas curiosity, subtlety and knowledge have falsehood in their train; the main qualities which conserve human society are humility, fear and goodness: they require a soul which is empty, teachable and not thinking much of itself.

139

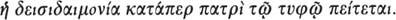

In Man curiosity is an innate evil, dating from his origins: Christians know that particularly well. The original Fall occurred when Man was anxious to increase his wisdom and knowledge: that path led headlong to eternal damnation. Pride undoes man; it corrupts him; pride makes him leave the trodden paths, welcome novelty and prefer to be the leader of a lost band wandering along the road to perdition; prefer to be a master of error and lies than a pupil in the school of Truth, guided by others and led by the hand along the straight and beaten path. That is perhaps what was meant by that old Greek saying, that Superstition follows Pride and obeys it as a father 140

140

[C] ‘Oh Pride! How thou dost trammel us!’ When Socrates was told that the god of Wisdom had called him wise, he was thunderstruck; he ransacked his mind and shook himself out but could find nothing to base this divine judgement upon. He knew other men who were as just, temperate, valiant and wise as he was: others he knew to be more eloquent, more handsome, more useful to their country. He finally concluded that, if he was different from others and wiser, it was only because he did not think he was; that his God thought any human who believed himself to be knowledgeable and wise was a singularly stupid animal; that his best teaching taught ignorance and his best wisdom was simplicity.

141

[A] The Word of God proclaims that those of us who think well of ourselves are to be pitied: Dust and ashes (it says to them) what have ye to boast about? And elsewhere: God maketh man like unto a shadow who will judge him when the light departeth and the shadow vanisheth?

142

In truth we are but nothing.

It is so far beyond our power to comprehend the majesty of God that

the very works of our Creator which best carry his mark are the ones we least understand. To come across something unbelievable is, for Christians, an opportunity to exercise belief; it is all the more reasonable precisely because it runs counter to human reason. [B] If it were reasonable, it would not be a miracle if it followed a pattern, it would not be unique. [C]

‘Melius scitur deus nesciendo’

[God is best known by not knowing], said St Augustine. And Tacitus says,

‘Sanctius est ac reverentius de actis deorum credere quam scire’

[It is more holy and pious to believe what the gods have done than to understand them].

143

Plato reckons that there is an element of vicious impiety in inquiring too curiously about God and the world or about first causes. As for Cicero, he says:

‘Atque ilium quidem parentem hujus universitatis invenire difficile; et, quum jam inveneris, indicare in vulgus, nefas’

[It is hard to discover the Begetter of this universe; and when you do discover him, it is impious to disclose him to the populace].

144

[A] We confidently use words like might, truth, justice. They are words signifying something great. But what that ‘something’ is we cannot see or conceive. [B] We say that God ‘fears’, that God ‘is angry’, that God ‘loves’:

Immortalia mortali sermone notantes

.

[Denoting immortal things in mortal speech.]

145

But they are disturbances and emotions which in any form known to us find no place in God. Nor can we imagine them in forms known to him. [A] God alone can know himself; God alone can interpret his works. [C] And he uses improper, human, words to do so, stooping down to the earth where we lie sprawling.

Take Prudence; that consists in a choice between good and evil; how can that apply to God? No evil can touch him. Or take Reason and Intelligence, by which we seek to attain clarity amidst obscurity; there is nothing obscure to God. Or Justice, which distributes to each his due and which was begotten for the good of society and communities of men; how can that exist in God? And what about Temperance? It moderates bodily pleasures which have no place in the Godhead. Nor is Fortitude in the face of pain, toil or danger one of God’s qualities: those three things are

unknown to him. That explains why Aristotle held that God is equally as free from virtue as from vice.

‘Neque gratia neque ira teneri potest, quod quae talia essent, imbecilla essent omnia’

[He can experience neither gratitude nor anger; such things are found only in the weak].

146

[A] Whatever share in the knowledge of Truth we may have obtained, it has not been acquired by our own powers. God has clearly shown us that: it was out of the common people that he chose simple and ignorant apostles to bear witness of his wondrous secrets; the Christian faith is not something obtained by us: it is, purely and simply, a gift depending on the generosity of Another. Our religion did not come to us through reasoned arguments or from our own intelligence: it came to us from outside authority, by commandments. That being so, weakness of judgement helps us more than strength; blindness, more than clarity of vision. We become learned in God’s wisdom more by ignorance than by knowledge. It is not surprising that our earth-based, natural means cannot conceive knowledge which is heaven-based and supernatural; let us merely bring our submissiveness and obedience: ‘For it is written: I will destroy the wisdom of the wise and bring to nothing the prudence of the prudent. Where is the wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the disputer of this world? Hath God not made the wisdom of this world like unto the foolishness as of beasts? For seeing that the world, through wisdom, knew not God, it pleased God through the vanity of preaching to save them that believe.’

147

But is it within the capacity of Man to find what he is looking for? Has that quest for truth which has kept Man busy for so many centuries actually enriched him with some new power or solid truth? Now, at last, it is time to look into that question.

I think Man will confess, if he speaks honestly, that all he has gained from so long a chase is knowledge of his own weakness.

148

By long study we have confirmed and verified that ignorance does lie naturally within us. The truly wise are like ears of corn: they shoot up and up holding their heads proudly erect – so long as they are empty; but when, in their maturity, they are full of swelling grain, their foreheads droop down and they show humility. So, too, with men who have assayed everything, sounded everything; within those piles of knowledge and the profusion of so many diverse things, they have

found nothing solid, nothing firm, only vanity. They then renounce arrogance and recognize their natural condition.

149

[C] For that is what Velleius reproached Cotta and Cicero with: they had learned from Philo that they had learned nothing.

150

When one of the Seven Sages of Greece, Pherecides, lay dying, he wrote to Thales saying, ‘I have commanded my family, once they have buried me, to send you all my papers; if you and the other Sages are satisfied with them, publish them; if not, suppress them: they contain no certainties which satisfy me. I make no claim to know what truth is nor to have attained truth. Rather than lay subjects bare, I lay them open.’

151

[A] The wisest man that ever was, when asked what he knew, replied that the one thing he did know was that he knew nothing.

152

They say that the largest bit of what we do know is smaller than the tiniest bit of what we do not know; he showed that to be true. In other words, the very things we think we know form part of our ignorance, and a small part at that. [C] We know things in a dream, says Plato; we do not know them as they truly are.

153

‘Omnes pene veteres nihil cognosci, nihil percipi, nihil sciri posse dixerunt; angustos sensus, imbecillos animos, brevia curricula vitae’

[Virtually all the Ancients say that nothing can be understood, nothing can be perceived, nothing can be known; our senses are too restricted, our minds are too weak, the course of our life is too short].

154