The complete idiot's guide to classical music (10 page)

Read The complete idiot's guide to classical music Online

Authors: Robert Sherman,Philip Seldon,Naixin He

Bet You Didn’t Know

Most audiences today revel in the melodic invention of Debussy’s “Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun,” but a Boston critic was less impressed in 1904. “The faun must have had a terrible afternoon,” wrote Louis Elson, “for the poor beast avoided all trace of soothing melody until the audience began to share his sorrows.” Another performance the following year took critic Elson back to his aisle seat, but he was still underwhelmed, writing “There are moments when Debussy’s suffering Faun seems to need a veterinary surgeon.”

Even when mood setting is not the intent, harmony enriches the melodic substance of a work, it expands the sounds, points up the low and high points of themes, adds richness and a wide variety to the tonal spectrum.

A scale—from the Italian “scala,” or stairway—is a progression of single notes, and like a staircase, the steps work equally well going up or down. A key is simply the name given to the notes of the scale, depending on where it starts and stops. If A is the base or “keynote,” and the rest of the scale functions in relation to it, it’s an A Major (or minor) scale, the notes progressing through B, C, D, E, F, G and back to A an octave (a span of eight notes) above.

Since the space relationships are the same whether the key is A, F, or anything else, the letters are sometimes replaced by syllables familiar to all crossword puzzle or

Sound of Music

fans. As Maria so aptly taught the kids, the keynote is “do” (as in “a female deer”), the one above that “re” (as in a “drop of golden sun”), and so on up through “mi,” “fa,” “sol,” “la,” “ti,” and back to “do” again.

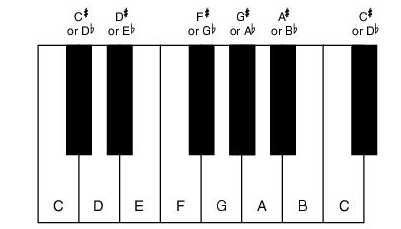

The best visual representation of this is the piano keyboard. The white keys are arranged in a seven-note sequence repeated throughout the keyboard. Within that octave are five black keys, in sequences of two and three, meaning that there are 12 tones in all, each one a half-step away from its neighbor. Because there are not twelve letters between A and G, the term “sharp” or “flat” is used to indicate that the note is one half-step up or down from the base note. A sharp is denoted by a “#” and a flat by a “ .” Thus the first black note in the sequence of two would be a C-sharp if it’s a halftone up from the basic key of C, but the same note would be a D-flat if it’s a halftone down from the basic key of D.

A score is a written piece of music. In writing music, a measure is a rhythmic division of music marked on the score as the distance between two vertical lines. The vertical line is referred to as a bar. The key signature is indicated by noting the appropriate sharps and flats on the left side of the ruled lines on the score.

A scale using all 12 tones (the seven white and five black notes within an octave) is called a chromatic scale; one using a specific selection of those notes, forming either a major or minor scale, is called diatonic. The major scales tend to have a bright, upbeat quality, most easily illustrated by starting on a C and playing only the white keys: i.e., C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C. A Major scale is made up of three whole tones followed by a half tone going up the scale. The minor scales reflect more melancholy moods. There are many types of minor scales but for the sake of simplicity we will discuss only the “natural minor.” Again starting on C is C-D-E -F-G-A -B -C.

Music Words

A

chromatic scale

is a scale based on an octave of 12 semitones, as opposed to a seven-note diatonic scale. A

major scale

is one built on the following sequence of intervals: T-T-D-T-T-T-S where T=tone and S=semitone. A

minor scale

is built on the following sequence of intervals: T-S-T-T-S-T-T.

Other selections of notes, often called modes, were in use during the Middle Ages, and are still used today in other cultures. Nor is the division of an octave into 12 tones universally accepted: Arabic music has 17 tones, several Czech composers have used quarter-tone scorings, the Mexican composer Julian Carrillo constructed instruments capable of producing sixteenth-tones, and the American Harry Partch built a harpsichord-like keyboard contraption with 43 tones to the octave.

Except for pieces in the 12-tone system, where every note is equal to every other note, most works—certainly those

written before the 20th century—have a tonal center. When a work is listed in C Major or F-sharp minor, it means that C (or F-sharp) is the basic tone on which the rest of the music is constructed. The piece may shift into other keys as the piece goes along, but even so, each section of the work maintains that sense of unity, gives us the feeling of starting from and returning to a home base. Usually, the sharps or flats that belong to each key are printed at the top of each score, at the left end of each line of music, and at any point within the score where the key changes; these listings are called key signatures. (In Mahler’s Symphony no. 6, there are episodes in all 24 major and minor keys, each of them marked by an appropriate shift in key signature.)

Important Things to Know

Composers choose different keys to evoke different moods. In very general terms, the major keys have a brighter, more optimistic sound, the minor ones are more melancholy, even somber. Then, even within those two primary divisions, each scale has a slightly different center of pitch, and therefore a somewhat different emotional cast. Most composers look on C Major as a bright, carefree key, for instance, while G minor often signifies music of more serious or dramatic nature. The layperson may not be able to distinguish between these keys; however, with experience you can tell the difference when a composer switches keys within a piece. The trained musician can tell the key on hearing it.

One way to indicate how a composer views these subtleties of sound and mood is to consider the keys of the Beethoven symphonies. The first two, shorter and lighter than most of the rest, are in the cheery majors of C and D Major, respectively.

The groundbreaking, revolutionary

Eroica

bears the more heroic key of E-flat. The charming Fourth Symphony is in B-flat, while the far more powerful Fifth Symphony is in C minor. In the

Pastoral Symphony,

the beauties of nature are displayed in the sunny key of F; the exhilarating Seventh dances along in A Major and the lighthearted (comparatively) Eighth returns to F Major. For the mighty Ninth Symphony, though, Beethoven chooses the darker key of D minor, until the “Ode to Joy” modulates to a jubilant D Major conclusion. Different composers, of course, will read widely diverse meanings into any given key, but that, as the saying goes, is what makes horse races.

Music Word

Modulation

is the shifting from one key to another within a musical composition, the idea being to accomplish this in a continuous musical flow. It’s no fair just stopping something in C Major and starting something else in G.

Color or timbre refers to the unique sound of each musical instrument of voice. A composer’s judicious use of color, and clever combinations of different timbres, can help shape a melody, emphasize the rhythmic foundation of a piece, or widen its emotional range. Some composers, including Rimsky-Korsakov and Scriabin, saw music as reflections of color, and believed that each key had its own special visual counterpart. Both used G-sharp minor to paint moonlight portraits, for instance, and E Major for rippling waters. Scriabin went much further in this color connection than his older colleague: He saw the key of C Major as red, F-sharp Major as bright blue, and so forth.

Bet You Didn’t Know

In his 1910 composition “Prometheus,” Scriabin wrote in a part for a color organ, a keyboard contraption intended to project changing colors in step with the musical progressions. The coordination was too complex, and the technology too primitive. It was not until 1975, 60 years after the composer’s death, that a reasonably successful fusion of music and color was accomplished (with a laser apparatus) at the University of Iowa.