The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (33 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

When you think of Rome, you probably think of the Colosseum, the great Roman amphitheater constructed by the emperors Vespasian (69â79) and Titus (79â81). Although you can find theaters and amphitheaters all over the Roman world, Roman buildings of these kinds were primarily built during the Empire. Rome didn't even

have

a permanent stone theater until Pompey the Great built one in 55

B

.

C

.

E

. and no permanent amphitheater until 29

B

.

C

.

E

.!

Nevertheless, it's important to distinguish between theaters and amphitheaters. Both of these buildings were developed for entertainment that, for the Romans, originated in temporary venues. Greek cities in Italy already had theaters, and when the Romans constructed their own permanent theaters, they used them as models. Theaters were composed of semicircular seating arrangements (the

theatron

âviewing place) around an orchestra (dancing circle), across from a raised platform for acting and a building

skene

(scene building) for backdrop and changing.

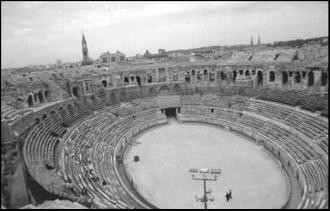

The amphitheater was another matter. The amphitheater evolved from the arena, a closed-off patch of ground surrounded by raised hills for viewing. The “ amphitheater” literally means “two (

amphi

)theatrons,” that is, two semicircular seating areas around an arena. The Romans used arenas for entertainment such as executions, hunts, and gladiatorial fights. The first amphitheaters were primarily seating enhancements (bleachers) added to the banks surrounding the arena. In time, however, the Romans created freestanding buildings and put their practical ingenuity into the creation of uniquely Roman entertainment centers.

The Roman Amphitheater in Nîmes, France.

Urban planning preceded the Romans (remember Egypt?), and was (in the Mediterranean) systematized as early as 550

B

.

C

.

E

. by the Greek architect Hippodamus. He proposed city planning on grid lines around a central marketplace; this became the model for the construction of Hellenistic cities founded after Alexander the Great.

The Romans based their urban planning, when they founded a colony, around the model of a Roman military camp, or

castra.

City walls were laid out in the shape of a square and fortified. Two principle streets (

viae principiae

) cut the square in half north-south (the

cardo

) and east-west (the

decamanus

) and met at a central forum. The streets met the walls at four city gates. Smaller streets were laid out parallel to the

cardo

and

decamanus,

forming blocks (

insulae

). At the corner of each

insula

a public fountain ran with water from the aqueduct. Each quadrant of the city had its purpose. In some cities, the lower rent districts were walled off from the wealthier citizens, a kind of early gated community.

In Rome, however, the Romans didn't have the advantage of beginning entirely from scratch. The Etruscan kings, who drained the marshes and created the civic, religious, and public spaces around which the later city grew, did the first central planning. Roman urban planning from then on consisted mostly of public works projects done on an

ad hoc

basis. The various forums were the public spaces in and around which most of this construction occurred. As Romans “romanized” foreign cities, they tended to focus rebuilding and development on forums and other urban projects that they identified with Roman civic identity. Urban planning, such as building codes and regulations (especially for fire), traffic regulation, and urban renewal projects, didn't begin until the very end of the Republic and Empire.

This sort of urban planning takes a kind of central authority that the Republic never had until Julius Caesar and Augustus made efforts to bring the teeming city into some kind of unified order. Of course, with such regulation came the dark minions of urban planning: boards of planning commissioners, inspectors, public works officials, and water meter readers.

The Romans were famous for their engineering and building when it came to war. Roman legions had their own engineers, builders, stone masons, and surveyors. Their camps, earthworks, siege equipment, and catapults were legendary, as well as their ability to create and construct under horrendous conditions and in remarkable time.

Roman military camps were set up, even while on the move, to protect troops and to serve as a defensive base. They had a standardized format so that everyone would know where things were, and troops were stationed within the walls according to military hierarchy. Camps were laid out in a square, surrounded by a ditch (

fossa

) and rampart walls of wood (

vallum

). Major encampments had towers added to the walls, and many permanent camps in the provinces became towns and then cities as settlements sprang up around them.

The camp was bisected by the

via principalis,

and troops were arranged by rank in lines perpendicular to it. There was a space of about 200 feet between the wall and the troops (

intervallum

). At the center stood the general's tent, the

praetorium,

flanked by centurions' tents and spaces for a forum and

quaestorium.

When camps were permanent, they included granaries to hold food, military hospitals, workshops, and VIP accommodations.

Siege Equipment

Â

Roamin' the Romans

British place names with “Chester” or “Caster” come from Roman military

castra

(camps) that were located in Great Britain. These former camps are easy enough to recognize by their names, but there were many more camps than modern place-names preserve: At least 550 Roman military sites have been identified on the island. There are fine exhibits and museums all over Britain concerning its Roman heritage, including ones at major sites in Chester, York, and along Hadrian's Wall.

When attacking a city, the Romans first surrounded it with walls and ditches to keep the enemy trapped in the city and to prevent supplies and reinforcements from getting in. The ring might extend for many miles in circumference. The Romans then set to breaching the walls of the town in one way or the other. Approaches and workers were protected by wooden sheds, which were built out of enemy range and extended toward the wall until it was reached. Catapults and other troops covered the workers and tried to keep the enemy off the walls. To aid in this, Caesar built his own raised walls that were higher than those of the besieged town so that his men could fire more easily onto the wall and into the town.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Catapults designed to shoot arrows and stones were first developed in Greece in the fifth century

B

.

C

.

E

. The Romans used two types of catapults: The

ballista

was a huge crossbow that shot arrows set afire; the

onager

shot stones. Each type of artillery came in various sizes.

Ballista

could fire arrows with deadly accuracy and in rapid succession depending on the size of projectiles that had to be loaded. Smaller

onegera

were mounted on wheels to be mobile. They shot either single stones or bags of stones, like huge shotguns, and had a range of about 1,400 feet. Large stationary

onagera

were the 16-inch guns of antiquity. They could hurl at the enemy up to 60-pound projectiles from half a mile away.

The main instrument for breaching the walls was an iron-tipped battering ram, called an

aries,

or a boring drill called a

terebra.

These were rolled up to the wall and were covered by a

testudo,

a structure with a fire-resistant roof. If they couldn't go through the wall, the Romans rolled a long work shed, called a

musculus

(mouse), up to the wall and dug a tunnel to the other side. Other times they constructed huge rolling assault towers and advanced them to the wall. From the top, soldiers would rain fire down on the defenders while a gangplank opened onto the wall and troops stationed inside the tower would rush across. With discipline in keeping supplies out and the inhabitants in, constant harassment of defenders, and aggressive try-and-try-again persistence, the Romans nearly always succeeded in finding a way to defeat a city.

- The Romans used their skills at tunneling, arches, and concrete to create enduring and practical structures.

- Roman roads were intended to serve in military defense. Major roads included sophisticated foundations, tunnels, road cuts, and elevated highways.

- Aqueducts were mostly constructed underground. Water distribution and plumbing were extremely sophisticated.

- Roman urban planning didn't begin until the end of the Republic. When Romans founded a small town they based its layout on the Roman

castra,

or military camp.

Empire Without End: Roman Imperial History

Rome wasn't over with the Republic. Not by a long shot: You still couldn't hit the end of the Roman timeline with the best

onager

(catapult). Augustus's Principate grew from the Republic's ashes into the Empire and at least another five hundred years of history. Or was it eight hundred years? Fourteen hundred? Fifteen? More?

The next six chapters take you through the rise and fall of the Roman Empire as it was centered on Rome. We'll see emperors from the ridiculous to the sublime and watch the center of power shift away from “old” Rome to the provinces and finally to

Nova Roma

(“New Rome”), or Constantinople. Did Rome “fall” or “fall apart” in the West under the avalanche of barbarian invasions? Or had it simply packed up and moved corporate headquarters with Constantine?