The Complete Pratt (145 page)

Read The Complete Pratt Online

Authors: David Nobbs

‘You’ve been a Socialist all your life, Henry,’ said Martin Hammond. ‘You’ve turned Liberal purely in order to get selected.’

‘I turned Liberal

before

I was selected,’ said Henry. ‘Yes, I believe in many of the Socialist aims – much greater social justice et cetera. I respect you. I don’t respect Tosser. That’s what we called Nigel at school.’

‘Is this relevant?’ protested Tosser.

‘No,’ said Henry, ‘but we’re on the telly purely because I’ve made an awful fool of myself, so I’m ruddy well going to say what I like.’ He looked straight into the camera, pretending it was Cousin Hilda. ‘I want to tell you what sort of man I am. Not tall, a bit fat, not brilliant, cocked up two marriages, sometimes drink too much, often feel useless, haven’t achieved a great deal,

but

…

but

I am deeply sincere, I love my country, for all its faults, I love this God-forsaken hole called Thurmarsh, I care about people and the world and I would love, just love, the chance to serve the community and my party and redeem my life.’

When he got back to Thurmarsh, Henry expected a ticking-off from Magnus.

‘I could hear you groaning,’ he said.

‘No, no,’ said Magnus. ‘No, no. You were right and I was wrong. You’re a one-off.’

Gallup gave the Tories a 2 per cent lead across the nation, with the Liberal vote up to 13 1/2 per cent.

Polling day was cold and bright, with occasional blustery showers. Henry cast his vote early. He voted for Martin Hammond, believing this to be the honourable thing to do. He spent the rest of the day touring the polling stations, encouraging the party workers. Everyone was in good spirits. Their vote was much higher than expected.

The Conservatives and the Socialists were also in good spirits. Their vote was much higher than expected as well.

If everybody who’d promised to vote for the three major parties had actually voted for them, the turn out would have been 167 per cent.

The count was held in the Town Hall, at long trestle tables. It was done at breakneck speed. Thurmarsh had secret hopes of being the first constituency to declare. It would be one in the eye for Torquay and Billericay.

Rumours began to sweep the hall. It was unexpectedly close. The Tories and the Socialists were neck and neck. The Liberals had done astonishingly well. Excitement grew. Martin Hammond looked sick at the unimagined possibility that he might lose. Tosser Pilkington-Brick looked sick at the unimagined possibility that he might win.

The candidates were informed that the Conservatives had won by five votes.

‘I don’t believe it,’ said Tosser, going ashen. ‘I demand a recount.’

‘But you’ve won,’ said the returning officer.

‘I demand a recount too,’ said Martin, who was shaking.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Tosser, recovering rapidly. ‘It’s the shock. This is beyond my wildest dreams. But I think it’s only right to have a recount. I must be sure of my mandate. That’s what I meant.’

As the recount began, Helen walked across the hall towards Henry. The conversational level dropped dramatically. All eyes were upon them. Henry could feel the blood rushing to his cheeks. He glanced uneasily at Diana. Helen’s eyes looked feverish, as if she had a temperature, but he knew that it was the result of excitement.

‘Is this wise?’ he said.

‘I was never wise,’ she said.

The conversation level in the hall rose again, and to new heights, as everybody discussed Henry and Helen.

‘It looks as though you may be doing all right,’ she said.

‘Yes. Not too bad, I think. You haven’t lost your job, I gather.’

‘No. No harm done, eh?’

Henry glanced at Diana again.

‘I wouldn’t say that,’ he said. ‘No, Helen, I wouldn’t say that.’

He could see Ted watching them from the middle of a knot of journalists at the far side of the hall. He could see the gleam in Ted’s eyes.

‘Well at least you got to appreciate my legs at last,’ said Helen.

‘I don’t remember them.’

‘What? You said they were the most beautiful legs you’d ever seen. You said they were the most beautiful things you’d ever seen in the whole world. I hoped you’d feel that had made it all worthwhile.’

‘Unfortunately, no. There’s no value in an experience you can’t remember. I’d like you to go now.’

‘Perhaps we’d better do it again some time when you’re sober, in that case.’

‘No, Helen. Now everybody’s looking at us out of the corners of their eyes so I suggest we shake hands and look as if we’re parting amicably. Otherwise I’ll turn away abruptly and it’ll look as if I’m snubbing you.’

‘Do you think I give a damn what people think of me?’ said

Helen

, and she turned away abruptly, leaving everyone in the hall to think that she was snubbing him.

The conversational level rose again.

Results were pouring in. It was clear that the Conservatives would win nationally. In Thurmarsh, the first recount gave Tosser a majority of one.

‘I demand another count,’ said Martin.

‘Absolutely. You must have one,’ said Tosser.

The second recount produced a dead heat. So far from being the first to declare, Thurmarsh looked as though it might have to carry on all night. Faces were ashen and drawn. The poor folk counting the votes were hollow with fatigue.

Martin looked devastated. So did Mandy. Tosser tried to look happy, but Felicity didn’t even make the effort. Diana was bored and tired and angry. Only Henry didn’t look devastated by the counting, and the rumour swept the hall that he had won.

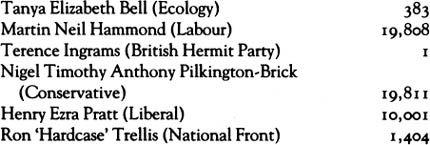

The result was finally announced, after five recounts, at ten past five.

It was:

There were loud cheers for Henry, who actually felt disappointed by the result, but even louder cheers, mixed with some booing, for Tosser, who managed, somehow, to smile and smile and smile. Felicity burst into tears at the result. ‘It’s the surprise,’ Tosser explained. ‘She’s overcome with joy at the privilege of helping to serve this town.’

Henry could hardly bring himself to smile. Tosser had won. Martin had lost. It was a disaster.

Still, he must follow the protocol. He dragged himself across to Tosser, smiling broadly, and holding out his hand.

‘Congratulations,’ he said. ‘Well done.’

‘Don’t be so bloody stupid,’ growled Tosser. ‘I’m going to have to buy a house in this disgusting town now. I’m going to have to visit it at weekends and hold surgeries. You bastard!’

‘What’s it got to do with me?’ asked Henry, bewildered.

‘You attacked me viciously, so all my supporters closed ranks behind me. You attacked Labour much more mildly, so their waverers all came over to you. Just don’t expect a Christmas card.’

‘I could cheerfully strangle you with my bare hands,’ said Felicity.

Henry walked less confidently towards Martin and Mandy. They couldn’t have looked more hostile if they’d been a couple of turkeys and he’d been Jesus Christ.

‘Well, you’ve really done it, haven’t you?’ said Martin. ‘You took our right wing

en masse

. You took nothing off him. Mrs Thatcher should give you a gong.’

‘Judas!’ said Mandy.

Tosser’s agent approached Henry.

‘Well done,’ he said, ‘and thank you. It was your success that saw us home.’

Henry smiled a sickly smile.

‘May I ask you a personal question?’ asked Tosser’s agent.

‘Go ahead,’ said Henry wearily.

‘They say that your wife, your very attractive wife if I may say so …’

‘Thank you.’

‘Was my candidate’s first wife.’

‘Yes. She was.’

‘Has she ever been in a mental institution of any kind?’

‘Good Lord, no.’

‘The bastard!’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘That was off the record. No, Nigel’s story has always been that

he

nursed his first wife through a long mental illness and eventually had to put her in a home, where she died.’

‘The bastard!’

‘But a winner.’

‘Not if I’d known that before today.’

‘Don’t worry. Our leader will be told what sort of man he is.’

‘Oh, please, no. It’ll get him promoted.’

Henry walked slowly towards the exhausted Diana.

Magnus bounced forward to intercept him.

‘Why so glum?’ he cried. ‘Ten thousand votes in South Yorkshire. This is an amazing, incredible, unprecedented triumph.’

Somehow, Henry couldn’t agree.

ONE SATURDAY MORNING

in 1981, almost two years after the General Election, as Henry was writing out his shopping list, the telephone rang.

‘Hello. Is that Henry Pratt?’ said a well-educated English establishment voice with not entirely successful pretensions to the fruitiness of eccentricity.

‘Yes,’ admitted Henry reluctantly.

‘Excellent. I’ve caught you. I

do

hope this isn’t an inconvenient time.’

‘What for?’

Almost Fruity laughed. ‘Very good! You’re everything I’ve been told.’

‘I don’t think I’ve said anything amusing and just what have you been told and what is this all about?’ said Henry drily.

‘Right. Sorry. Anthony Snaithe. Overseas Aid. You’ve been suggested to me as a possible manager of one of our aid schemes. It would involve spending at least two years in Peru. Are you thunderstruck?’

‘Well, yes. Yes, I am.’

‘What do you say?’

‘Well, good Lord, I … er … I mean, here I am … and suddenly to think of going to Peru, I … er … I mean there are so many things to take into account. I couldn’t just say “yes” straight away.’

‘No. Quite. Quite. But the significant thing to me is that you haven’t said “no” straight away. You are prepared to entertain the prospect as a possibility, then?’

Henry looked round his bare, bachelor flat. He thought of the coming day – making his shopping list, going to Safeway’s, going to the pub for a couple, watching the rugby, maybe nodding off, having a shower, going to the pub for a couple, cooking himself

something

from the stuff he bought at Safeway’s, eating it, switching the television on and nodding off in the chair.

‘Yes, I am,’ he said.

‘Good. We should meet for lunch. When can you come down to town?’

‘Well, I haven’t my work diary with me, but I should think I could come down to town any day the week after next.’

‘Shall we say Tuesday week?’

‘Fine.’

‘Good. Do you know the Reliance Club?’

‘Er … no.’

‘Oh! Well, the food’s only passable, but they do a legendary spotted dick.’

As the train slid slowly towards London, Henry’s excitement grew. Peru. ‘Manager of our aid scheme.’

Here at last was something to fill the yawning gap left by the collapse of his political ambitions. The Liberals had begged him to continue, but his electioneering memories had become inextricably bound up with the scandal on the green baize, his loss of Diana, and Tosser’s victory, and he hadn’t the heart to continue.

Here at last was something to free him from the emptiness that he’d felt ever since that morning, the day after the General Election, when Diana had packed all her things for the removal men, had denuded the house of its charm and vitality, had kissed him on the cheek and said, ‘It hasn’t really worked for some years, has it? Goodbye, my darling,’ and he had stood there with the tears streaming down his face but hadn’t called her back.

He opened his

Guardian

and there was an article about Peru in it. A good omen, even if the unfortunate misprint in the headline, which read,

THE LAND OF THE SOARING CONDOM,

seemed an echo of his own past disasters.

He read about condors and pan pipes, Inca ruins and pelicans, the mighty Amazon and the stupendous Andes, and realised how deeply, how terminally bored with cucumbers he had become.

Excitement beckoned. He began to feel nervous. As he passed

through

the double doors of the grimy stone fortress that housed the Reliance Club, he wished he was taller than his measly five foot seven.