The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler (23 page)

Read The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Reggie Oliver

‘Princess Frederica’s coming the weekend after next,’ he said, and groaned. (Sophisticated readers will know which late member of the Royal Family I mean by Princess Frederica; the rest will have to be content with their ignorance. It really does not matter, anyway.)

‘Did you invite her?’ I asked.

‘You don’t invite Princess Frederica. She invites herself. It’s particularly bloody because Selena Selby’s coming down that weekend. I’m rather keen on her actually.’

‘The Blue Room?’

‘She’s a sweet girl. Anyway, it happened that I was at this awful bash in London a week or so ago at Clarence House. God knows why! And there was H.R.H. Frederica. Well, we’ve met on several occasions because she used to holiday a lot on Micky Dorset’s private island off Guadaloupe and I used to go too. So she latched on to me and started going on about how she had heard so much about Swincombe, and how she would love to see it, blah, blah. You know how she goes on. . . . Well, perhaps you don’t. And the next thing I know she’s made me invite her down for the weekend.’

‘It can’t be that bad surely?’

‘Good God, it’s worse! Don’t you know about Princess Frederica coming to stay? No, I suppose you don’t.’ Johnnie fished a crumpled piece of paper out of his jeans and tossed it on to the coffee table in front of him. ‘That came from her office this morning.’

At this point Pat and Robert came in with the champagne, and, once the drinks were poured, we all settled down to study the document.

In it a certain Lady Florence Cardew (‘Lady in Waiting to H.R.H. Princess Frederica’) set down what Her Royal Highness was to expect from a visit to Swincombe. It was certainly thorough, and listed in detail not only what the Princess would like to eat and drink, but whom she would like to meet and where she would like to go. Many of the provisions were concerned with what Princess Frederica would

not

like. For example:

‘Her Royal Highness will eat potatoes, but not plain boiled, and not “chips”.’

Evidently the proletarian word ‘chips’ was so offensive to her that it had to be placed within the protective barriers of inverted commas. Again:

‘Her Royal Highness will drink only Glen Gowdie Single Malt [a notoriously expensive and hard to obtain brand] with Evian water (half and half) before meals. She may also drink it with meals, but will accept (though not necessarily drink) a glass of claret (Premier Cru Bordeaux only, please) with the meal. A bottle of Glen Gowdie Single Malt and a bottle of Evian water is to be placed by her bedside.’

Even Robert, a devoted royalist, had to concede that she did seem ‘a little demanding’. The letter also stipulated whom she would like to be invited to have lunch and dinner with her, but conceded: ‘You may invite three or four people of your own choice, provided that their names are submitted for vetting at least a week in advance.’ There and then Johnnie decided that we should come to lunch on the Sunday to lend, as he put it, ‘moral support’. I glanced at Robert. His expression reminded me of Bernini’s celebrated statue of St Teresa at Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. The saint has just been pierced by an arrow of Divine Love, and a look of sanctified sensual ecstasy suffuses her entire being.

I have confused memories of the lunch with Princess Frederica. We were briefly introduced and I must reluctantly concede that she did possess an odd kind of glamour. That once legendary beauty was still somehow present, hovering like a ghost about her lined and leathery face, darting in and out of those intensely blue eyes. When told that I was in the theatre, she remarked:

‘Oh, God! Not another actor!’

They were the only words she spoke to me, not notably gracious ones at that. I would like to record that I came back with a witty retort, but I did not. (One doesn’t.) I retired crushed.

The lunch, which took place in the large and chilly dining room, I remember chiefly for two things. I remember my brother-in-law embarrassing me inordinately because he laughed loudly at almost everything the Princess said. Secondly, I noticed sitting next to the Princess, an exquisitely beautiful ash-blond girl in her mid-twenties with a dreamy expression. Johnnie’s ideal, I thought. I asked the well-bred nonentity sitting next to me if this was Selena Selby.

‘

Lady

Selena Selby, yes,’ he replied with a reproachful sniff for my ignorance.

After the meal Princess Frederica, for whom some elaborate post-lunch diversion had been contrived, suddenly decided that what she wanted was a nap and marched off to her bedroom, leaving the rest of us at something of a loss. Johnny proposed a walk and a reassembly for tea at four. I saw him glance urgently in my direction: it was clear he wanted to confide.

By walking fast and climbing up narrow paths by the old cascade we managed to shake off the others. I asked him how it was going, or some similarly feeble question.

‘Did you see Selena at lunch next to H.R.H?’ he asked.

I nodded.

‘Lovely, isn’t she? I put her in the Blue Room.’

‘I see.’

‘Yes. Well. It was pretty agonising actually, because H.R.H. wouldn’t go to bed last night at a decent hour, so of course we all had to stay up to keep her company. She would insist on chain smoking and playing this bloody game called Canasta. You know how she is. Oh, no, I was forgetting. Of course you don’t. Well, it was past midnight before she eventually decided she’d had enough.’

Johnnie told me that it was almost half past one before he could make his way along the draughty corridors of Swincombe towards the Blue Room and Lady Selena. He opened the door and heard a voice whisper: ‘Close the door behind you.’ He did so and found himself in complete darkness. He asked Selena to switch on the light, but she, whispering again, refused. By this time the atmosphere of the Blue Room was beginning to have its effect on him. His head began to pound with sexual longing. He groped his way to the bed, encouraged by her lubricious whisperings, and the next moment, it seemed to him, he was engulfed in a bout of the most torrid lovemaking he had ever experienced.

‘The Blue Room was working its magic all right and in spades,’ said Johnnie. ‘Even I was a bit startled by it all. Either it was the room or Selena herself, but she seemed to know all the tricks. The only thing she wouldn’t do was let me turn on the lights. Well, by the end of it I was too exhausted to do anything more. I just collapsed and in less than half a minute I was dead to the world.

‘It must have been five when I woke. There was a crack in the curtains which threw this shaft of grey light into the room. I could see Selena’s shape under the duvet. It was a surprisingly bulky shape for Selena, who’s a slip of a thing, as you know. Well, that surprised me, but then I saw two things on the bedside table which made me go awfully numb. I wonder if you can guess what they were.’

‘A bottle of Glen Gowdie Single Malt and a bottle of Evian water?’

‘Bloody Hell. Got it in one! Selena and H.R.H. must have swapped bedrooms without my knowing. I’d had my way with an elderly Royal. I can tell you, I was out of that bedroom and into my own in double quick time. I couldn’t go to sleep again, so I dressed and wandered about the house. At about half past seven I happened to come in to the Long Drawing Room, and blow me, there was H.R.H., in a dressing gown, smoking a fag on one of the Chinese Chippendale day beds.’

Conversation between Johnnie and the Princess, I gathered, was pretty sticky, but eventually he plucked up enough courage to tell her that he didn’t know that she had moved to the Blue Bedroom. Princess Frederica was quite cool about it and totally unapologetic. She said:

‘It was too late to tell you. Selena and I agreed to swap bedrooms. I didn’t like mine very much. That shade of yellow in those damask curtains is not me at all. Blue happens to be my favourite colour. You should have known that.’

Johnnie then tried to explain that he did not want her to get the wrong impression from last night, that he had been unaware that it had been her, that. . . . He floundered.

There was a long pause before Princess Frederica said: ‘You don’t honestly imagine that I didn’t know all about the Blue Room, did you?’

By this time, Johnnie told me, he was in a state of complete shock, or, as he put it, ‘feeling like a rabbit at a stoat’s tea party’. Princess Frederica rose from the day bed, ground the remains of her cigarette into the Aubusson carpet with her heel, and drifted to the window. She gazed dreamily out on to the croquet lawn where, as if by Royal Command, the sun emerged from behind a cloud and made the morning dew sparkle.

‘Lady Selena is such a sweet girl. I am very fond of her,’ she said. ‘Did you know she is one of my goddaughters?’

Johnnie shook his head. The Princess moved away from the window and began to advance towards him rather deliberately. For a moment he thought he was going to be hit. Johnnie braced himself for the Royal clout, but it did not come. Instead she just patted his cheek. ‘There was a look on her face that was almost human,’ Johnnie told me. ‘Humorous, even.’

‘Let that be a lesson to you,’ said the Princess.

A NIGHTMARE SANG

There can be few more excruciating experiences for a dramatist than to see one’s play badly performed. Despite this, a mixture of vanity, curiosity and optimism always compelled Daniel Pinson, a forty year old playwright of some distinction, to go to see his work on stage whenever the opportunity arose. That was why one evening in early August he attended an amateur production of his two-act historical drama

The Poisons Affair

at the Jubilee Hall, Bidmouth. However, to save himself more embarrassment than was strictly necessary, he went incognito.

It was quite by chance that he had found himself in Bidmouth, and that the Bidmouth Players happened to be producing his play, which four years previously had enjoyed a respectable run in the West End. Pinson had been giving a course of lectures for the Department of Theatre Studies at Truro University. When the term finished, he had decided to give himself a brief holiday in the West Country before returning to London. There had been little to return to. A long-term relationship had broken up some months before, which was one of the reasons why he had gone to Truro.

Pinson had been staying with friends inland and it was they who told him that, if he wanted to spend a quiet few days on the coast, Bidmouth was the sort of place he might like. It was a picturesque old Devon fishing port, not overrun with tourists but lively enough, with one or two good seafood restaurants. His friends recommended a bed and breakfast boarding house and Pinson booked himself in for three nights.

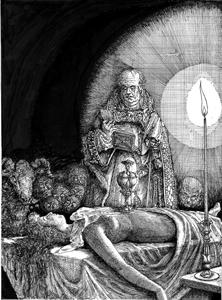

On his first evening in Bidmouth Pinson had seen a poster for his play stuck up with sellotape in a shop window. The crude artwork, in black on pink paper, had obviously been designed by someone who had no idea what the play was about, but had made a rough guess from the title. A skull reposed under a lighted candle, corrugated with gouts of wax, next to which stood a bottle, helpfully labelled POISON. Pinson read that the last night of the show was the following evening.

When he bought a ticket at the tourist office next morning it was gratifying to find that he had secured one of the last seats available. That, and the fact that it was a fine, refreshing summer’s day put him in good spirits. Pinson was someone who found solitude invigorating. He walked around the town with its narrow lanes and quaint cobbled streets, letting his mind take hold of whatever it fancied, hoping it would lead him to the subject of his next play. He had been blocked ever since Francine had left him.

Every time he saw a poster for his play he would stop and examine it with a secret smile on his lips. After a hearty fish and chip lunch at one of the little cafés on the quay he went in search of the Jubilee Hall, so that he would know exactly where to go that evening.

Outside the hall—a strange architectural mélange of neo-Classical and Byzantine—hung a board which displayed the play’s poster and a number of production photos which Pinson examined with interest. The use of flash photography, customary in amateur productions, gave the scenes they depicted a coarse, two-dimensional effect, and exposed the crudities of the actors’ make-up. But Pinson noted with pleasure that the costumes were authentic and well-made, in fact outstandingly good for non-professionals. In addition, from a physical point of view, the actors and actresses seemed to have been well cast for their roles.

The Poisons Affair

was about the celebrated scandal at the court of Louis XIV in which various prominent members of his entourage, including his mistress Madame de Montespan, were implicated in acts of poisoning and, worse, black magic. Pinson, a writer noted for his economy and sense of form, had reduced the cast of characters to six: three men and three women. It was a play about sex and power and prejudice; it was also a kind of thriller; it had been a success.

That evening before the show, in a pub opposite the Jubilee Hall, Pinson had a light early supper of smoked salmon sandwiches and whisky. He had never been a heavy drinker, but he sometimes used alcohol in carefully calculated amounts to ease the burden of his sorrows. On this occasion he decided that two large whiskies with ginger ale would suffice to take the edge off any frustration he might feel at the performance’s inadequacies.

They were enough too to make him feel a warm glow of affection for the cheerful, mostly middle-aged audience that was piling into the small foyer of the hall. Did they know that they were about to witness a rather sinister historical melodrama? They seemed wholly bent on innocent amusement. Pinson worried, but only a little and bought himself a programme which entitled him, he noticed, to ‘a free interval glass of wine’. This was just as well, because the programme was otherwise not very good value. It contained little information about the play and none at all about its author beyond the bare mention of his name.

The seats were not numbered so he went into the auditorium early and found himself a place on an aisle where he could stretch his long legs. It was a traditional municipal entertainment hall with plastic stacking chairs on the flat wooden floors and a high, raised stage at one end. Pinson spent fifteen entertaining minutes watching his audience—they were always ‘his’ in his mind—enter, find their places, greet old friends, chatter inanely. Five minutes after the play was due to begin, when the hall was packed, the lights dimmed; a fragment of recorded Lully blared out through the loudspeakers and, with a little death rattle, the curtains were drawn apart.

One of the aspects of amateur acting which always surprises professionals is not that it is bad but that it so often lacks what one would have expected it to have in abundance: gusto, energy, enthusiasm. By and large amateurs do not go ‘over the top’, they go under it, often so far under as to be inaudible. These actors, at least, were not inaudible, but they were distinctly under-powered. Rage and passion came over as mild annoyance or tepid desire; anything more subtle barely registered. The moves had been carefully worked out but were executed mechanically without much reference to what was being felt. All the same, Pinson was gratified to find that the audience was listening intently to his words and laughing heartily at the wit, even when it was delivered less than convincingly.

Finding the performance itself unengrossing he began to speculate about the lives of the actors on stage. The most accomplished of them was the woman playing the leading role of Madame de Montespan, whose name, he saw from the programme, was Jean Crowden. She was in her forties and though not exactly beautiful she had the big, blowsy but still voluptuous figure that Montespan herself must have had at the time of the poisons scandal. She moved awkwardly, but she had a certain panache. Pinson observed with amusement that she got all her laughs by the simple method of saying her wittiest lines slightly louder than she said the rest.

In spite of himself Pinson experienced a frisson of sexual interest. How would she react, he wondered, if he were to introduce himself as the great author of her lines? He shrugged away the thought. After all, he had just finished a protracted affair with Francine Allen, the brilliant actress who had portrayed Montespan in the original West End production.

Another performer attracted his attention for a rather different reason. This was the man who played the part of the Abbé Guibourg. Guibourg was the villainous renegade priest who was reputed to have sacrificed babies in black magic ceremonies so that Montespan might preserve her hold over King Louis. The Bastille records, unusually for them, describe his physical appearance in some detail. Guibourg had been a large, bloated, one-eyed man with a hideous face and a blotchy red complexion.

The scene in which Guibourg makes his first appearance is laid at night in the gardens of Versailles. His sinister figure, all in ecclesiastical black, suddenly emerges from the leafy shadows. It is a powerful moment and, on this occasion even Pinson, who was expecting it, received a shock. The actor playing Guibourg was so exactly as Pinson had imagined him: over six feet four, loose-bellied, with red-veined and pendulous jowls, one eye covered by a black patch, the other bloodshot. The effect was incomparably sinister, far more so even than the West End production. Pinson looked at the cast list in his programme. The name of the actor playing Guibourg was Alec Crowden, obviously related to Jean who played Montespan. But how? As husband, brother, or father even?

Unfortunately, Alec Crowden’s performance did not live up to the impact of his first appearance. His mind seemed to be elsewhere; he spoke his lines as if in a dream, but at least he looked the part.

For Pinson the pace of the production was unbearably slow, so, when the interval came, he decided that perhaps after all he would not stay for the second half. Seeing his work performed was a bittersweet experience at the best of times and, in this instance, bitterness had predominated. He would claim his free interval wine and then exchange the stuffiness of the Jubilee Hall for the clean sea air outside, an inviting prospect only slightly vitiated by lingering curiosity. Pinson was just draining his glass of tepid Liebfraumilch when he heard a voice behind him.

‘You are Daniel Pinson and I claim my five pounds!’

Pinson snarled angrily to himself, but by the time he had turned round to face the speaker he was wearing an engaging smile. The man who had addressed him was rather older looking than he had expected from the voice. He was bald, neat, spectacled, cardiganed and carried a clipboard. A concession to the artistic had been made by his sporting of a brightly coloured cravat around his neck.

‘I’m sorry?’ said Pinson.

‘You are Daniel Pinson, are you not?’ It was a thin, pedantic, annoying voice. Pinson would have liked to have said no, but he could tell that he would not have been believed and even more annoyance would have resulted from a denial. He nodded.

‘Ron Titlow, President and Principal Director of the Bidmouth Players,’ said the man, extending his hand. Pinson shook it. Titlow’s grip was cold, dry and surprisingly strong.

‘So!’ said Titlow, lowering his voice to a mock conspiratorial murmur. ‘We are travelling incognito, are we?’

‘You could say that.’

Titlow tapped his nose with a biro. ‘Have no fear! Your secret is safe with me. Another glass of vino?’

‘No thank you.’

Pinson saw that he would have to make himself agreeable to Titlow. He told him that he had come across the Bidmouth Players’ production quite by accident. Titlow was surprised: hadn’t he been informed by his agent or his publishers? The fact was that amateur productions showed up on Pinson’s quarterly royalty statement from French’s, the play publishers, and that was the first and last he knew or wished to know about them. Titlow seemed a little put out that Pinson had not been ‘apprised’, as he put it. (Titlow was head of the English Department at Bidmouth Comprehensive.)

‘You do know this is the West of England Amateur Première of your play?’ said Titlow.

Pinson put on his suitably impressed expression.

‘Oh, yes. We pride ourselves on being rather ahead in terms of quality and innovation, you know. A little bit

avant garde

, as they say. Our production of

The Dance of Death

came second in the Amateur Dramatic Regional Finals last year.’

Pinson reinvigorated his features to adopt the same look as before. A bell rang to recall the audience to their seats. Pinson was not going to be able to escape.

‘Now tell me honestly,’ said Titlow. ‘Be as frank as you like. Speaking as the expert here. In your professional opinion, what do you think of our little production?’ Pinson hesitated. Another bell sounded. ‘No, don’t tell me now! Wait till you’ve seen the second half. Tell you what, we’re having a little last-night, post-show celebration. Why don’t you join us? Not a few bottles of the bubbly will be cracked, I can tell you. We’d really be honoured.’

‘Well. . . .’

‘That’s marvellous. My little company will be absolutely thrilled.’

‘Don’t tell them now,’ said Pinson. ‘It might put them off.’

Titlow laughed, a curious falsetto giggle. ‘You bet I won’t. This is going to be our little surprise. Wait in the foyer after the show. I’ll come and collect you.’ The last bell rang. With that, Pinson re-entered the hall and Titlow disappeared into the lighting box.

The second half for Pinson was even more tedious than the first, with the exception of one moment. This involved the Abbé Guibourg. In the penultimate scene Guibourg, now in captivity, languishes in a cell in the prison of Vincennes. Because of his connection with the King’s mistress he was not allowed to stand trial, but was condemned instead to perpetual solitary confinement. He has somehow acquired a bottle of wine and is singing a raucous song in his cell. It is one of those moments which playwrights create for which actors take most of the credit. The song is defiant, uproarious but at the same time utterly despairing. Done well it left an unforgettable impression on the audience.

Pinson had almost dozed off in the stifling heat of the hall when he heard the song, but something about it awakened him to full consciousness. It was as if a glass of iced water had been poured down his back. He stared at the stage where Guibourg was ranting out the song, waving his bottle in the air. Here was a man surviving in a state of living death pouring out his last maledictions upon a world he hated. Pinson realised that the actor on stage had achieved what perhaps only a non-professional can occasionally realise, a complete, unmediated identification with a character without the aid of technique or artifice. At that moment the man simply was Guibourg, the drunken, despairing Satanist, raving upon the lip of Hell. Pinson noted that the audience too were aware of it. They were watching the man on stage in an awed, alarmed silence, and, in the mortal stillness which followed the conclusion of the song, a young woman got up from her seat and ran precipitately from the auditorium, her sobbing breaths audible to all.