The Conflict (14 page)

Authors: Elisabeth Badinter

PART THREE: OVERLOADING THE BOAT

1

Michelle Stanworth, ed.,

Reproductive Technologies: Gender, Motherhood, and Medicine

(Cambridge: Polity Press, 1987), p. 14. Carolyn M. Morell also points out that women's situations have become even worse. With the changes that have happened in the work environment and family structure, women's responsibilities in terms of child care are defined far more rigorously than in the past. A mother's responsibilities just keep on increasing. See

Unwomanly Conduct: The Challenges of Intentional Childlessness

(New York: Routledge, 1994), p. 65.

Reproductive Technologies: Gender, Motherhood, and Medicine

(Cambridge: Polity Press, 1987), p. 14. Carolyn M. Morell also points out that women's situations have become even worse. With the changes that have happened in the work environment and family structure, women's responsibilities in terms of child care are defined far more rigorously than in the past. A mother's responsibilities just keep on increasing. See

Unwomanly Conduct: The Challenges of Intentional Childlessness

(New York: Routledge, 1994), p. 65.

2

See the novels and essays by Marie Darrieussecq, Nathalie Azoulai, Ãliette Abécassis, and Pascale Kramer.

3

As Lyliane Nemet-Pier observes with such acuity, a child has become a precious creature but one that must not get in the way. See

Mon enfant me dévore

(Paris: Albin Michel, 2003), p. 12.

Mon enfant me dévore

(Paris: Albin Michel, 2003), p. 12.

5. THE DIVERSITY OF WOMEN'S ASPIRATIONS

1

Pascale Donati, “Ne pas avoir d'enfant: construction sociale des choix et des constraints à travers les trajectories d'hommes et de femmes,”

Dossier d'études

, no. 11, Allocations familiales (2000): 22.

Dossier d'études

, no. 11, Allocations familiales (2000): 22.

2

Pascale Pontoreau,

Des enfants, en avoir ou pas

(Montreal: Les Ãditions de l'Homme, 2003), pp. 8â9.

Des enfants, en avoir ou pas

(Montreal: Les Ãditions de l'Homme, 2003), pp. 8â9.

3

Linda M. Blum,

At the Breast: Ideologies of Breastfeeding and Motherhood in the Contemporary United States

(Boston: Beacon Press, 1999), p. 6.

At the Breast: Ideologies of Breastfeeding and Motherhood in the Contemporary United States

(Boston: Beacon Press, 1999), p. 6.

4

Sharon Hays,

The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood

(New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), pp. 6â9.

The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood

(New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), pp. 6â9.

5

A woman who has never had children. The French word

nullipare

is the title of a novel by Jane Sautière (Paris: Verticales, 2008).

nullipare

is the title of a novel by Jane Sautière (Paris: Verticales, 2008).

6

Sautière,

Nullipare

, p. 13 [translator's note: some liberties have been taken with this extract because the resonance of the French words cannot be reproduced in English].

Nullipare

, p. 13 [translator's note: some liberties have been taken with this extract because the resonance of the French words cannot be reproduced in English].

7

Catherine Hakim,

Work-Lifestyle Choice in the 21st Century

(Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 51â52.

Work-Lifestyle Choice in the 21st Century

(Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 51â52.

8

Isabelle Robert-Bobée, “Ne pas avoir eu d'enfant: plus frequent pour les femmes les plus diplômées et les hommes les moins diplômés,”

France, portrait social

, National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies, 2006, p. 184: “More than 20% of women born in 1900 had no children as compared to 18% of women born in 1925 and 10 to 11% for the generations born between 1935 and 1960.”

France, portrait social

, National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies, 2006, p. 184: “More than 20% of women born in 1900 had no children as compared to 18% of women born in 1925 and 10 to 11% for the generations born between 1935 and 1960.”

9

Pascale Donati, “La non-procréation: un écart à la norme,”

Informations sociales

, no. 107 (2003): 45. This group represents 2 to 3 percent of women.

Informations sociales

, no. 107 (2003): 45. This group represents 2 to 3 percent of women.

10

Michel Onfray,

Théorie du corps amoureux

(Paris: LGF, Le Livre de Poche, 2007), p. 218.

Théorie du corps amoureux

(Paris: LGF, Le Livre de Poche, 2007), p. 218.

11

Ibid., pp. 219â20.

12

Rosemary Gillespie, “Childfree and Feminine: Understanding the Gender Identity of Voluntarily Childless Women,”

Gender & Society

17, no. 1 (February 2003): 122â36.

Gender & Society

17, no. 1 (February 2003): 122â36.

13

Annily Campbell,

Childfree and Sterilized: Women's Decisions and Medical Responses

(London: Cassell, 1999).

Childfree and Sterilized: Women's Decisions and Medical Responses

(London: Cassell, 1999).

14

See the works of the sociologists Jean E. Veevers (Canada) and Elaine Campbell (Great Britain) and the psychologist Mardy S. Ireland (United States), who questioned hundreds of childless

women. In France this question has aroused interest only much more recently: see the works of Pascale Donati, Isabelle Robert-Bobée, and Magali Mazuy.

women. In France this question has aroused interest only much more recently: see the works of Pascale Donati, Isabelle Robert-Bobée, and Magali Mazuy.

15

Magali Mazuy,

Ãtre prêt-e, être prêts ensemble? Entrée en parentalité des hommes et des femmes en France

(doctoral thesis in demography, Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, September 2006).

Ãtre prêt-e, être prêts ensemble? Entrée en parentalité des hommes et des femmes en France

(doctoral thesis in demography, Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, September 2006).

16

Donati, “Ne pas avoir d'enfant,” p. 37.

17

Mardy S. Ireland's term from

Reconceiving Women: Separating Motherhood from Female Identity

(New York: Guilford Press, 1993).

Reconceiving Women: Separating Motherhood from Female Identity

(New York: Guilford Press, 1993).

18

Jean E. Veevers, “Factors in the Incidence of Childlessness in Canada: An Analysis of Census Data,”

Social Biology

19, no. 3 (1972): 266â74. See also Veevers,

Childless by Choice

(Toronto: Butterworths, 1980).

Social Biology

19, no. 3 (1972): 266â74. See also Veevers,

Childless by Choice

(Toronto: Butterworths, 1980).

19

Leslie Lafayette,

Why Don't You Have Kids? Living a Full Life Without Parenthood

(New York: Kensington Books, 1995). Elinor Burkett,

The Baby Boon: How Family-friendly America Cheats the Childless

(New York: Free Press, 2000). Maryanne Dever and Lisa Saugères, “I Forgot to Have Children!: Untangling Links Between Feminism, Careers and Voluntary Childlessness,”

Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering

6, no. 2 (2004): 116â26.

Why Don't You Have Kids? Living a Full Life Without Parenthood

(New York: Kensington Books, 1995). Elinor Burkett,

The Baby Boon: How Family-friendly America Cheats the Childless

(New York: Free Press, 2000). Maryanne Dever and Lisa Saugères, “I Forgot to Have Children!: Untangling Links Between Feminism, Careers and Voluntary Childlessness,”

Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering

6, no. 2 (2004): 116â26.

20

Donati, “Ne pas avoir d'enfant,” p. 20.

21

Ibid.

22

JaneMaree Maher and Lise Saugeres, “To Be or Not to Be a Mother?: Women Negotiating Cultural Representations of Mothering,”

Journal of Sociology

43, no. 1 (2007): 5â21. Firsthand accounts and results of semi-structured interviews with a hundred women. This study adds to Leslie Cannold's study,

What, No Baby?:

Why Women Are Losing the Freedom to Mother, and How They Can Get It Back

(Fremantle, Australia: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 2005).

Journal of Sociology

43, no. 1 (2007): 5â21. Firsthand accounts and results of semi-structured interviews with a hundred women. This study adds to Leslie Cannold's study,

What, No Baby?:

Why Women Are Losing the Freedom to Mother, and How They Can Get It Back

(Fremantle, Australia: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 2005).

23

Hays,

The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood.

The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood.

24

Maher and Saugeres, “To Be or Not to Be a Mother?” p. 5.

6. WOMBS ON STRIKE

1

See Francis Ronsin,

La grève des ventres: propagande néo-malthusienne et baisse de la natalité français, XIX

e

âXX

e

siècles

(Paris: Aubier Montaigne, 1980).

La grève des ventres: propagande néo-malthusienne et baisse de la natalité français, XIX

e

âXX

e

siècles

(Paris: Aubier Montaigne, 1980).

2

Laurent Toulemon, Ariane Pailhé, and Clémentine Rossier, “France: High and Stable Fertility,”

Demographic Research

19, article 16 (July 1, 2008): 503â56. According to their projections, 11 percent of women born in 1970 and 12 percent of those born in 1980 would remain childless (pp. 516 and 518).

Demographic Research

19, article 16 (July 1, 2008): 503â56. According to their projections, 11 percent of women born in 1970 and 12 percent of those born in 1980 would remain childless (pp. 516 and 518).

3

Dylan Kneale and Heather Joshi, “Postponement and Childlessness: Evidence from Two British Cohorts,”

Demographic Research

19, article 58 (November 28, 2008): 1935â68. They indicate that 9 percent of women born in 1946 remained childless whereas 18 percent of those born in 1958 and 1970 did.

Demographic Research

19, article 58 (November 28, 2008): 1935â68. They indicate that 9 percent of women born in 1946 remained childless whereas 18 percent of those born in 1958 and 1970 did.

4

Alessandra De Rose, Filomena Racioppi, and Anna Laura Zanatta, “Italy: Delayed Adaptation of Social Institutions to Changes in Family Behaviour,”

Demographic Research

19, article 19 (July 1, 2008): 665â704. The authors indicate that 10 percent of women born in 1945 remained childless and 20 percent of those born in 1965 (p. 671).

Demographic Research

19, article 19 (July 1, 2008): 665â704. The authors indicate that 10 percent of women born in 1945 remained childless and 20 percent of those born in 1965 (p. 671).

5

Alexia Prskawetz, Tomáš Sobotka, Isabella Buber, Henriette Engelhardt, and Richard Gisser, “Austria: Persistent Low Fertility

Since the Mid-1980s,”

Demographic Research

19, article 12 (July 1, 2008): 293â360.

Since the Mid-1980s,”

Demographic Research

19, article 12 (July 1, 2008): 293â360.

6

Jürgen Dorbritz, “Germany: Family Diversity with Low Actual and Desired Fertility,”

Demographic Research

19, article 17 (July 1, 2008): 557â98. The author points out that these are estimates: 7 percent of women born in 1935, 21 percent of those born in 1960, and 26 percent of those born in 1966. He also notes that only Switzerland compares with Germany on this subject.

Le Monde

, October 20, 2009, made the point that 29 percent of West German women born in 1965 have remained childless.

Demographic Research

19, article 17 (July 1, 2008): 557â98. The author points out that these are estimates: 7 percent of women born in 1935, 21 percent of those born in 1960, and 26 percent of those born in 1966. He also notes that only Switzerland compares with Germany on this subject.

Le Monde

, October 20, 2009, made the point that 29 percent of West German women born in 1965 have remained childless.

7

Figures from 2006 published by the US Census Bureau in August 2008.

8

Australian Bureau of Statistics report, “Women in Australia, 2007,” Australian Government, 2007. See also Janet Wheeler, “Decision-making Styles of Women Who Choose Not to Have Children” (paper presented at the 9th Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference, Melbourne, Australia, February 9â11, 2005). See also Jan Cameron,

Without Issue: New Zealanders Who Choose Not to Have Children

(Canterbury, New Zealand: Canterbury University Press, 1997).

Without Issue: New Zealanders Who Choose Not to Have Children

(Canterbury, New Zealand: Canterbury University Press, 1997).

9

In Thailand the number of childless women more than doubled between 1970 and 2000, going from 6.5 percent to 13.6 percent. See P. Vatanasomboon, V. Thongthai, P. Prasartkul, P. Isarabhakdi, and P. Guest, “Childlessness in Thailand: An Increasing Trend Between 1970 and 2000,”

Journal of Public Health and Development

3, no. 3 (SeptemberâDecember 2005): 61â71.

Journal of Public Health and Development

3, no. 3 (SeptemberâDecember 2005): 61â71.

10

Like most former Eastern bloc European countries including Russia, but also Greece, Portugal, and Spain. See INED, Indi-cateurs

de fécondité, 2008, Eurostat estimates,

http://www.ined.fr/fr/pop_chiffres/pays_developpes/indicateurs_fecondite/

.

de fécondité, 2008, Eurostat estimates,

http://www.ined.fr/fr/pop_chiffres/pays_developpes/indicateurs_fecondite/

.

11

Joanna Nursey-Bray,

“Good Wives and Wise Mothers”: Women and Corporate Culture in Japan

(thesis submitted to the Centre for Asian Studies at the University of Adelaide, 1992). See also Muriel Jolivet,

Un pays en mal d'enfants: crise de la maternité au Japon

(Paris: La Découverte, 1993). This book describes Japanese women's revolt against the crushing role of the traditional mother.

“Good Wives and Wise Mothers”: Women and Corporate Culture in Japan

(thesis submitted to the Centre for Asian Studies at the University of Adelaide, 1992). See also Muriel Jolivet,

Un pays en mal d'enfants: crise de la maternité au Japon

(Paris: La Découverte, 1993). This book describes Japanese women's revolt against the crushing role of the traditional mother.

12

From 1982 to 2007, there was a steady rise in the percentage of Japanese women aged fifteen to thirty-nine who worked. It went from 49.4 percent to 59.4 percent, the rise becoming much more pronounced since 2002. See the Japanese Bureau of Statistics, which can be viewed at

http://www.stat.go.jp/english/info/news/1889.htm

.

http://www.stat.go.jp/english/info/news/1889.htm

.

13

In 2004, 62 percent of west Germans (compared to 29 percent in eastern Germany alone) felt that children suffered if the mother worked and that pursuing a career and being a mother were incompatible. Women who tried to do it were perceived as bad mothers, as

Rabenmütter

(mother crows who no longer care for their young when they fall from the nest). Cited by Heike Wirth,

Kinderlosigkeit von hoch qualifizierten Frauen und Män-nern im Paarkontext: eine Folge von Bildungshomogamie?

(Wiesbaden, Ger.: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2007), pp. 167â99.

Rabenmütter

(mother crows who no longer care for their young when they fall from the nest). Cited by Heike Wirth,

Kinderlosigkeit von hoch qualifizierten Frauen und Män-nern im Paarkontext: eine Folge von Bildungshomogamie?

(Wiesbaden, Ger.: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2007), pp. 167â99.

14

Since January 2004, new legislation came into effect with a view to improve child-care facilities for children under three.

15

Toulemon et al., “France: High and Stable Fertility,” pp. 505â6.

16

Chikako Ogura, a psychologist and a professor at Waseda University in Tokyo, was quoted by

L'Express

, September 12,

2009, in the excellent report: “Les Japonaises ont le

baby blues

.” In Italy, by contrast, women still want to have childrenâtwo, on average. Alessandra De Rose et al., “Italy: Delayed Adaptation of Social Institutions to Changes in Family Behaviour,” pp. 682â83. The authors pointed out that 98 percent of women aged twenty to twenty-nine would like to have children, that the number of children wanted is an average of 2.1, and that this number remains unchanged even among women who have invested heavily in academic qualifications and have professional ambitions.

L'Express

, September 12,

2009, in the excellent report: “Les Japonaises ont le

baby blues

.” In Italy, by contrast, women still want to have childrenâtwo, on average. Alessandra De Rose et al., “Italy: Delayed Adaptation of Social Institutions to Changes in Family Behaviour,” pp. 682â83. The authors pointed out that 98 percent of women aged twenty to twenty-nine would like to have children, that the number of children wanted is an average of 2.1, and that this number remains unchanged even among women who have invested heavily in academic qualifications and have professional ambitions.

17

Prskawetz et al., “Austria: Persistent Low Fertility Since the Mid-1980s,” pp. 336â37: in 2005, only 4.6 percent of children under three and 60.5 percent of all children between three and school age benefited from public child care. Furthermore, their opening hours and long closures for holidays made them impractical.

18

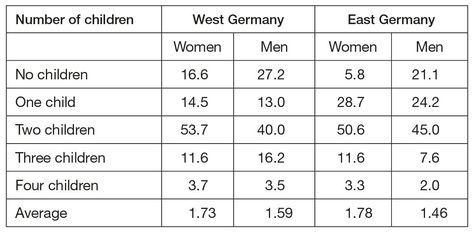

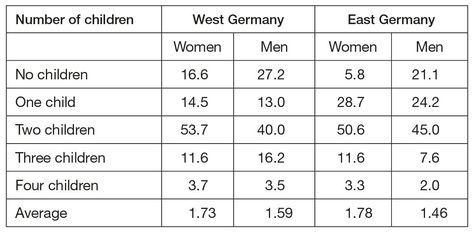

Dorbritz, “Germany: Family Diversity with Low Actual and Desired Fertility,” pp. 583â84, featuring figures for the number of children people in Germany wanted in 2004 (average).

19

Yve Ströbel-Richter, Manfred E. Beutel, Carolyn Finck, and Elmar Brähler, “The âWish to Have a Child,' Childlessness and Infertility in Germany,”

Human Reproduction

20, no. 10 (2005): 2850â57.

Human Reproduction

20, no. 10 (2005): 2850â57.

20

See Ursula Henz, “Gender Roles and Values of Children: Childless Couples in East and West Germany,”

Demographic Research

19, article 39 (August 22, 2008): 1452.

Demographic Research

19, article 39 (August 22, 2008): 1452.

21

The salary gap between men and women is still the best indicator of the situation. We can confirm that it is still universally in men's favor.

22

See the TNS-Sofres survey for

Philosophie Magazine

, “Pourquoi fait-on des enfants? Le sondage qui fait réagir,” 27 (March 2009): 21. When asked: “Why have children?” 73 percent of the answers were connected to pleasure.

Philosophie Magazine

, “Pourquoi fait-on des enfants? Le sondage qui fait réagir,” 27 (March 2009): 21. When asked: “Why have children?” 73 percent of the answers were connected to pleasure.

23

Ãmilie Devienne,

Ãtre femme sans être mère: le choix de ne pas avoir d'enfant

(Paris: Robert Laffont, 2007), pp. 96â98.

Ãtre femme sans être mère: le choix de ne pas avoir d'enfant

(Paris: Robert Laffont, 2007), pp. 96â98.

24

Elaine Campbell,

The Childless Marriage: An Exploratory Study of Couples Who Do Not Want Children

(London: Tavistock Publications, 1985), p. 51.

The Childless Marriage: An Exploratory Study of Couples Who Do Not Want Children

(London: Tavistock Publications, 1985), p. 51.

25

Ibid., p. 49.

26

Kristin Park, “Choosing Childlessness: Weber's Typology of Action and Motives of the Voluntary Childless,”

Sociological Inquiry

75, no. 3 (August 2005): 372â402.

Sociological Inquiry

75, no. 3 (August 2005): 372â402.

27

See Ãdith Vallée,

Pas d'enfant, dit-elle ⦠les refus de la maternité

(Paris: Imago, 2005). Caroline Eliacheff and Nathalie Heinich,

Mères-filles, une relation à trois

(Paris: Albin Michel, 2002).

Pas d'enfant, dit-elle ⦠les refus de la maternité

(Paris: Imago, 2005). Caroline Eliacheff and Nathalie Heinich,

Mères-filles, une relation à trois

(Paris: Albin Michel, 2002).

28

Nicole Stryckman, “Désir d'enfant,”

Le Bulletin Freudien

, no. 21 (December 1993).

Le Bulletin Freudien

, no. 21 (December 1993).

29

Gérard Poussin,

La fonction parentale

(Paris: Dunod, 2004), quoted in the excellent article by Geneviève Serre, Valérie Plard, Raphaël Riand, and Marie Rose Moro, “Refus d'enfant: une autre voie du désir?”

Neuropsychiatrie de l'enfance et de l'adolescence

56, no. 1 (February 2008): 9â14.

La fonction parentale

(Paris: Dunod, 2004), quoted in the excellent article by Geneviève Serre, Valérie Plard, Raphaël Riand, and Marie Rose Moro, “Refus d'enfant: une autre voie du désir?”

Neuropsychiatrie de l'enfance et de l'adolescence

56, no. 1 (February 2008): 9â14.

30

See Jane Bartlett,

Will You Be Mother? Women Who Choose to Say No

(New York: New York University Press, 1994), pp. 107â11; Elaine Campbell,

The Childless Marriage

, pp. 37â41; Marian Faux,

Childless by Choice: Choosing Childlessness in the Eighties

(Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1984), pp. 16â17.

Will You Be Mother? Women Who Choose to Say No

(New York: New York University Press, 1994), pp. 107â11; Elaine Campbell,

The Childless Marriage

, pp. 37â41; Marian Faux,

Childless by Choice: Choosing Childlessness in the Eighties

(Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1984), pp. 16â17.

31

Pascale Donati, “Ne pas avoir d'enfant: construction sociale des choix et des constraints à travers les trajectories d'hommes et de femmes,”

Dossier d'études

, no. 11, Allocations famiales (2000): 15.

Dossier d'études

, no. 11, Allocations famiales (2000): 15.

32

Philippe Ariès, “L'enfant: la fin d'un règne,” in “Finie, la famille?”

Autrément série

“Mutations” (1992): 229â35. Philippe Ariès attributes the decline in birthrates to hedonistic Malthusianism. We have shifted from the child-king to the child-hindrance who compromises fulfillment for the individual and the couple.

Autrément série

“Mutations” (1992): 229â35. Philippe Ariès attributes the decline in birthrates to hedonistic Malthusianism. We have shifted from the child-king to the child-hindrance who compromises fulfillment for the individual and the couple.

33

Donati, “Ne pas avoir d'enfant,” pp. 31â32.

34

Faux,

Childless by Choice

, pp. 42â43; Cameron,

Without Issue

, pp. 61â64 and 74â76.

Childless by Choice

, pp. 42â43; Cameron,

Without Issue

, pp. 61â64 and 74â76.

35

Marsha D. Somers, “A Comparison of Voluntarily Child-free Adults and Parents,”

Journal of Marriage and the Family

55, no. 3 (August 1993): 643â50. Cameron,

Without Issue

, p. 75. Sherryl Jeffries and Candace Konnert, “Regret and Psychological Well-Being Among Voluntarily and Involuntarily Childless Women and Mothers,”

International Journal of Aging and Human Development

54, no. 2 (2002): 89â106.

Journal of Marriage and the Family

55, no. 3 (August 1993): 643â50. Cameron,

Without Issue

, p. 75. Sherryl Jeffries and Candace Konnert, “Regret and Psychological Well-Being Among Voluntarily and Involuntarily Childless Women and Mothers,”

International Journal of Aging and Human Development

54, no. 2 (2002): 89â106.

36

Sandra Toll Goodbody, “The Psychosocial Implications

of Voluntary Childlessness,”

Social Casework

58, no. 7 (1977): 426â34. See also Joshua M. Gold and J. Suzanne Wilson, “Legitimizing the Child-free Family: The Role of the Family Counselor,”

Family Journal

10, no. 1 (January 2002): 70â74.

of Voluntary Childlessness,”

Social Casework

58, no. 7 (1977): 426â34. See also Joshua M. Gold and J. Suzanne Wilson, “Legitimizing the Child-free Family: The Role of the Family Counselor,”

Family Journal

10, no. 1 (January 2002): 70â74.

37

Park, “Choosing Childlessness,” p. 375. She points out that surveys on comparative marital satisfaction in couples with or without children produced different conclusions. According to some, there is no significant difference; others found there was greater satisfaction within childless couples. In 1995 the British Office of Population Census and Survey showed that the divorce rate is higher in parents of children under the age of sixteen and lower in those with children over this age. The divorce rate for childless couples lay in between the two.

38

Cameron,

Without Issue

, p. 23.

Without Issue

, p. 23.

39

Elinor Burkett,

The Baby Boon: How Family-friendly America Cheats the Childless

(New York: Free Press, 2000), p. 182.

The Baby Boon: How Family-friendly America Cheats the Childless

(New York: Free Press, 2000), p. 182.

40

Julia Mcquillan, Arthur L. Greil, Karina M. Shreffler, and Veronica Tichenor, “The Importance of Motherhood Among Women in the Contemporary United States,”

Gender & Society

22, no. 4 (August 2008): 480.

Gender & Society

22, no. 4 (August 2008): 480.

41

The Swedish demographers Jan M. Hoem, Gerda Neyer, and Gunnar Andersson published a very interesting article exploring the subtleties of this statement. According to them, it is less the level of education that is the determining factor than the professional orientation chosen. When women choose a feminized job (public service, teaching, medical world, etc.), they have more children than those committed to masculine territories (private enterprise, jobs with irregular working hours). However, they bring to light some counterexamples to their hypothesis that limit the

scope of their ideas. See “Education and Childlessness: The Relationship Between Educational Field, Educational Level, and Childlessness Among Swedish Women Born in 1955â59,”

Demographic Research

14, article 15 (May 9, 2006): 331â80.

scope of their ideas. See “Education and Childlessness: The Relationship Between Educational Field, Educational Level, and Childlessness Among Swedish Women Born in 1955â59,”

Demographic Research

14, article 15 (May 9, 2006): 331â80.

Other books

Garan the Eternal by Andre Norton

Reggie's: Changing a Wolf's Heart by Jana Leigh

Futures and Frosting by Tara Sivec

Primal by Serra, D.A.

Over the Fence by Elke Becker

The Silver Eyed Prince (Highest Royal Coven of Europe) by Dunraven, VJ

What Are Friends For? by Rachel Vail

The Butterfly Conspiracy by James Nelson

SNAP! and the Alter Ego Dimension by Ann Hite Kemp