The Conquering Tide (11 page)

Read The Conquering Tide Online

Authors: Ian W. Toll

The destroyer

Patterson

was the first to raise the alarm. By TBS (“talk-between-ships,” a short-range voice radio used for tactical communications) she signaled, “Warning, warning, strange ships entering harbor.”

35

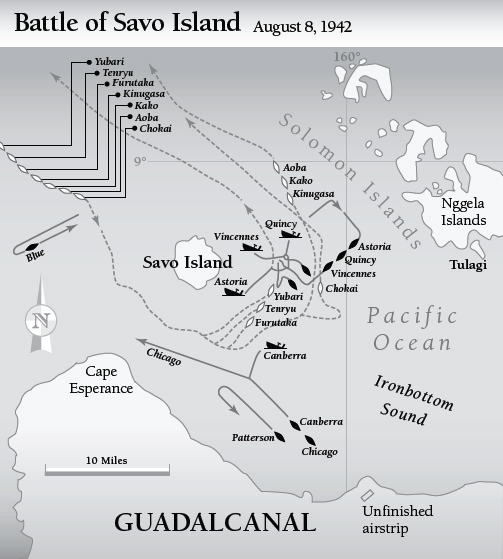

But the Long Lances were already away, and the Japanese cruiser planes, circling overhead, dropped flares directly over the two cruisers, lighting them up for the gunners. At 1:44, Mikawa's ships opened a devastating salvo of 8-inch and 6-inch armor-piercing shells. The

Canberra

and

Chicago

, on a course of 310 degrees at a speed of 13 knots, were caught by surprise. Struck by at least twenty shells and two torpedoes, the

Canberra

blazed all along her length. Most of her senior officers, including Captain Frank Getting, were killed by direct hits on the bridge and superstructure. She lost all propulsion and electrical power, took on a ten-degree starboard list, and shuddered to a stop.

36

The

Chicago

, just astern, steered to avoid her. Captain Bode ordered star shells fired in the direction of the enemy salvos, but they either failed to fire or were duds. Two torpedoes narrowly missed the

Chicago

, but a third hit and tore open her starboard bow. A gunnery officer recalled, “The deck beneath me came up under my feet, and the turret door to the officer's booth flew open. . . . Through the open turret door I could see two broad pencil streaks of phosphorescence in the water, parallel to the hull of the ship. They were the wakes of two torpedoes that had missed.”

37

Chicago

could fight no more. She had no power, her cruiser planes were spilling burning aviation fuel all along her upper works, and her forward compartments were flooding rapidly. Captain Bode apparently made no attempt to radio a warning to the other ships of the task force, a failure for which he would later be censured.

The action south of Savo Island had consumed less than ten minutes. Mikawa's column, racing east at 30 knots, veered north. While executing the turn, the cruisers

Tenryu

,

Yubari

, and

Furutaka

diverged from the rest of the column and took a more westerly course. Though Mikawa had not intended it, this maneuver had the effect of dividing the Japanese force into two roughly parallel columns that enveloped the three American cruisers and two destroyers of the northern group, which were steaming at 10 knots on a heading of 315 degrees in a column led by the

Vincennes

. The gunfire to the south had been heard, but officers in the northern cruiser group apparently assumed it must be friendly. The radio rooms on

Quincy

,

Astoria

, and

Vincennes

had each copied the

Patterson

's warning, but on the

Vincennes

it did not reach the captain, who remained fast asleep in his emergency cabin near the pilothouse. Men went to battle stations, but the speeding attackers overtook their quarry quickly.

Flares dropped by Japanese cruiser planes descended through the overcast and bathed the three American cruisers in brilliant greenish-yellow light. A few seconds later, the

Chokai

's searchlight flashed over their sterns. Once again, the Japanese launched torpedoes and thenâbefore the fish reached their targetsâopened a salvo of devastating and accurate shellfire. One of Mikawa's officers, Toshikazu Ohmae, observed that the

Chokai

's searchlight served the double function of leading the column and spotting targets. As if by an unspoken seaman's language, wrote Ohmae, the flagship was “fairly screaming to her colleagues: âHere is the

Chokai

! Fire on

that

target! . . . Now

that

target! . . . This is the

Chokai

! Hit

that

target!' ”

38

On the

Astoria

, Captain William G. Greenman was shaken awake, but his first order upon reaching the bridge was to cease fire. The bleary-eyed skipper was sure the southern group had somehow blundered into the northern group and was firing on it in confusion. In these critical moments,

Astoria

was battered by 5- and 8-inch shells on both quarters and peppered along her length by 25mm machine-gun fire. One heavy projectile struck the barbette of turret No. 1, knocking the weapon out of action and killing all personnel in the area. Another slammed home in the No. 1 fireroom, and a third struck a kerosene tank on the starboard side amidships, spilling blazing fuel across the well deck. According to the damage report, the ship quickly “become a raging inferno from the foremast to the after-bulkhead of

the hangar. These fires eventually necessitated the abandoning of the firerooms and engine rooms due to intense heat and dense smoke.”

39

Steering control was lost on the bridge, but that was moot as the ship soon lost all headway. All the forward fire main risers having ruptured, no water could be pumped to the hoses.

The

Quincy

was badly mauled on both quarters as her crew was rushing to stations. She was struck several times in the 1.1-inch antiaircraft mounts on the main deck aft. Firing back gamely, her main batteries delivered an 8-inch shell into the

Chokai

's operations room, just abaft her bridge.

Chokai

's turret No. 1 was knocked out of action, and her floatplanes, mounted on catapults, burst into flame. The

Quincy

's skipper, Captain Moore, ordered a starboard turn to avoid colliding with the

Vincennes

. But another devastating salvo severed the steering leads, jammed the rudder in place, and held the ship in her turn until she was struck by two torpedoes on the port side near her firerooms, killing her propulsion. At 2:10 a.m., the

Quincy

's bridge was wiped out by two direct shell hits, killing Moore and most of the senior officers. Upon reaching the scene, an assistant gunnery officer “found it a shambles of dead bodies with only three or four people still standing.”

40

The

Quincy

listed heavily to port. As the sea poured into the shell holes in her hull, her upper decks were soon awash and she rolled onto her beam ends. Survivors threw rafts and other floatable objects into the sea, and then followed. Lieutenant Commander Bion B. Bierer, a supply officer, dived into the sea and swam about a hundred feet away. Treading water, he turned to watch the finale: “She went down by the bow and at a very sharp angle, her stern with propellers and rudder clearly outlined against the fire-lit sky.”

41

Captain Frederick Lois Riefkohl of the

Vincennes

, shaken awake by a crewman, likewise hesitated to engage the searchlights for fear that they might be friendly. Before the ship's signalmen could send recognition signals, the ship was battered by too many projectiles to countâperhaps as many as seventy-four, fired by four or five different Japanese cruisers. The initial salvos struck the bridge, the carpenter shop, the hangar, and the antenna trunk. All the

Vincennes

's gun turrets were disabled by direct or near shell hits. Fires sprang up throughout those areas, the floatplanes in the hangar lit up like tinderboxes, and the enemy fire did not let up for a moment. Direct shell hits were sustained on sky aft and sky forward. To add

to her tally of grief, the

Vincennes

caught two torpedoes on her port side, near the forward magazine. Fires raged out of control all along her length, and great rippling explosions threw sheets of flame into the sky. An analysis published by the navy's Bureau of Ships later concluded, “It is not possible for any lightly protected vessel [i.e., a non-battleship] to absorb such punishment and survive.”

42

Riefkohl ordered the crew off the ship at 2:14, and the

Vincennes

went down thirty minutes later.

At 2:16 the Japanese ships, still steaming at 30 knots, cleared Savo Sound and headed up the Slot. The

Ralph Talbot

, belatedly attempting to join the action, found herself directly in Mikawa's path. Lit up by searchlights and mauled by five shell hits, her radar, radio communications, and fire control equipment were all destroyed.

43

The hull plating on her starboard quarter was torn open at about the waterline, and she took on a 20 percent starboard list. Had a timely rain shower not descended over her, shrouding her from the enemy's view, she would likely have been blown out of the water.

To the marines on Guadalcanal and Tulagi, and the crews of the XRAY and YOKE transports in Savo Sound, the terrific roar and reverberations of the big guns had been accompanied by distant flashes in the mist. A searchlight occasionally stabbed through the night, and red tracer lines spat out here and there, but it was impossible to draw any firm conclusions from what they could see and hear. “We could clearly hear the thunder of guns, and see the sky light up from explosions,” said a witness on Tulagi, “but knew only what the crews of the landing boats told us, that there was a naval battle going on.”

44

On the

McCawley

, Turner and Vandegrift came up on deck to watch the pyrotechnics. Sailors on the flagship cheered wildly, assuming that the American ships were letting the enemy have it. Very soon silence returned, and all that could be seen were a few distant fires, apparently blazing ships. It was not yet known whether they were Allied or enemy.

Richard Tregaskis watched the show from Lunga Point. He had known that a counterattack by sea was likely, but the tremendous cannonading brought home a terrible truth. The marines on Guadalcanal were not in charge of their fate. “In that moment I realized how much we must depend on ships even in our land operation. . . . The terror and power and magnificence of man-made thunder and lightning made that point real. One

had the feeling of being at the mercy of great accumulated forces far more powerful than anything human. We were only pawns in a battle of the gods, then, and we knew it.”

45

The sea was littered with debris and dead bodies. Hundreds of men who had abandoned the sinking ships clung to rafts or wreckage and struggled to remain afloat. Lieutenant Harry Vincent of the

Vincennes

, having leapt into the sea about fifteen minutes after Riefkohl's order to abandon ship, found himself among a group of sixteen sailors, all treading water. The stronger swimmers removed their life belts and gave them to the men who appeared most in need. Vincent recalls, “We discovered we could tread water without a belt for thirty minutes and then hang on to a sailor with a belt for thirty minutes and then do it again and again.”

46

The battle and the sinking ships had stirred up the phosphorus in the sea, and men could look down to a depth of 15 or 20 feet. Sharks occasionally patrolled beneath their feet, but none attacked. Fred Moody, also of the

Vincennes

, was similarly proud of his shipmates. “Even these boys that were wounded out there, I didn't hear anyone calling for help for himself. Everyone seemed to want to help the other guy. That was my impression. I know certainly it was that way for the rest of the night.”

47

They stayed afloat in this manner until daybreak, when the destroyer

Chambers

came alongside and lowered a cargo net.

M

IKAWA ELECTED TO RETIRE AT HIGH SPEED TO THE NORTHWEST,

rather than return to Savo Sound to engage the XRAY and YOKE transport groups. That was a fateful decision, and for the Americans a very lucky one. If the admiral had taken the more aggressive course, as some of his officers had urged, Turner's fleet might have been wiped out. In that case, the logistical underpinning of

WATCHTOWER

might have collapsed, with bleak consequences for Vandegrift's marines.

Mikawa's caution has been criticized, particularly by Western historians. But the admiral later offered a trenchant defense of the decision. He had been informed, incorrectly, that the Japanese air raids on August 7 and 8 had destroyed a large portion of the American transport fleet, so he did not expect to find a great wealth of targets. His column was traveling at high speed, and its formation had become disordered. Herding them back into a

coherent formation and charging back into Savo Sound might have taken as long as two or three hours. Most importantly, he could not know that Fletcher's carriers had retired to the east and posed no danger.

Mikawa had thus far wagered his ships, and won. To renew the attack, he believed, would expose his force to a carrier air attack while he lacked any defense except antiaircraft guns; he would be inviting the same sort of catastrophe that he had recently witnessed at Midway. After the war, the admiral acknowledged that he might have scored a fantastic victory had he chosen differently, but he insisted that he could act only on the basis of what he knew at the time:

Knowing now that the transports were vital to the American foothold on Guadalcanal, knowing now that our army would be unable to drive American forces out of the Solomons, and knowing now that the carrier task force was not in position to attack my ships, it is easy to say that some other decision would have been wiser. But I believe today, as then, that my decision, based on the information known to me, was not a wrong one.

48