The Conquering Tide (69 page)

Read The Conquering Tide Online

Authors: Ian W. Toll

Airstrikes on enemy airfields always commenced with a fighter sweep. Elements of several different Hellcat squadrons coalesced into a tremendous air formation, typically numbering sixty or seventy aircraft. The pilots flew in compact formations, often with little more than 3 or 4 feet between wingtips. They arrived over the target at high altitude and dove on any Japanese fighters that rose to meet them. With decisive advantages in speed, defensive armor, and firepower, the F6Fs made short work of their adversaries. David S. McCampbell, the most prolific navy ace of the Second World War, led his

Essex

Hellcats into several major air battles in 1944. He always made a point of targeting the enemy leaders firstâ“it may throw the rest of the pilots off a little bit, disrupt the formation.” According to McCampbell, the Hellcat squadrons had no use for the “Thatch Weave,” a tactic designed to compensate for the F4F Wildcat's inferior speed and maneuverability against the Zero. The F6F was a better aircraft than the Zero in every respect, and therefore suited to more aggressive tactics. One quick burst of .50-caliber fire, aimed into the Zero's vulnerable wing-root, and “they would explode right in your face.”

8

By early 1944, these initial fighter sweeps usually wiped the sky clean of Japanese fighters, and when the dive-bombers and torpedo bombers arrived some minutes later, they encountered little or no remaining air opposition.

Rear Admiral Mitscher, who flew his flag in the

Yorktown

, emphasized that the entire carrier task force was just a sophisticated support system for its aviators. “Pilots are the weapon of this force,” he told his staff. “Pilots are the things you have to nurture. Pilots are people you have to train, and you have to train other people to support the pilots.”

9

He was a small, wiry man with a gaunt and weathered face. There was barely a hair left on his head, and he used the call sign “Bald Eagle.” Rarely did Mitscher ever leave the

Yorktown

's flag bridge. He was usually perched on a stool, dressed in wrinkled khakis and a faded duck-billed cap, with a pair of binoculars on a strap around his neck. He normally had very little to say, but he listened carefully and absorbed everything his pilots told him. When he did speak, it was in a wan, raspy voice, and he was not always successful in making himself understood. Jocko Clark, his first flagship captain, said he had to teach himself to read lips in order to decipher the admiral's words.

Arleigh Burke, Mitscher's longtime chief of staff in Task Force 58, observed that the admiral often had an uncanny sense of what the enemy was about to do, and he was usually right. He was not clairvoyant, said Burkeâhe simply had the intuition of a veteran aviator who had been flying from carriers as long as any pilot in the navy. His expectations were high, and he did not hesitate to relieve a man who failed to meet them. “He was a little bit of a fellow, a sandblower, who was a magnificent commander,” Burke said. “He knew his pilots; he knew his job; he was skillful himself. . . . He was wise, he was simple, he was direct, and he was ruthless.”

10

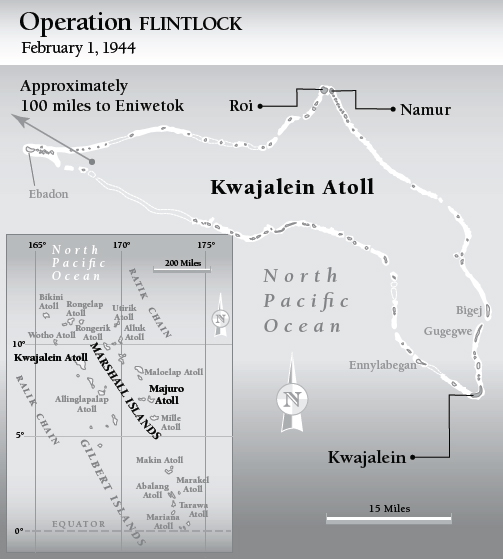

T

HE INEXORABLE ATTRITION

of Japanese airpower in the central Pacific had been underway since long before

FLINTLOCK

. At the end of December 1943, the Americans had four working airfields in the Gilberts, including three that could accommodate heavy bombers. Rear Admiral John H. Hoover's land-based air command sent USAAF bombers against the eastern Marshalls from rear bases at Canton and Ellice Islands and new bases at Makin and Tarawa. The workhorse of this campaign was the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, often escorted by F6Fs or P-39 Airacobras. The raiders noted a steady decline in the number of enemy fighters that rose to meet them. Navy PB4Ys, a naval version of the B-24, flew reconnaissance missions over the islands and laid mines in the channels. Nimitz's headquarters diary recorded the near-daily “milk runs” that preceded the

FLINTLOCK

landings. On January 21, fifteen B-24s dropped 30 tons of bombs on Roi-Namur and Kwajalein islands. The next day, ten B-24s dropped 20 tons of bombs on Roi; on January 29, five B-24s left 13 tons; on January 30, seven B-24s added another 21 tons. Mille, Jaluit, Malelop, Taroa, and Wotje were all bombed heavily on the same day.

11

On the morning of January 28 (D-Day minus three), Admiral Frederick C. Sherman's Task Group 58.3 landed a knockout blow on the airfield at Kwajalein Island. The dawn F6F sweep encountered no Japanese fighters at all, and the bomber squadrons that followed ensured that the airfield would not return to action before the amphibious fleet arrived. The next day, Sherman's group struck Eniwetok, the westernmost of Japan's fortified Marshalls atolls, and gave it the same kind of treatment. Sherman's carriers remained off Eniwetok for three days while their air groups pulverized the airfields and ground installations. On the third day, not much was left but

heaps of rubble and a few palm trees that had been completely stripped of their foliage. The airmen reported that they could not find any targets on the ground or in the lagoon that seemed worth bombing, and “the island looked like a desert waste.”

12

The warships assigned to bombard the landing beaches came over the eastern horizon before dawn on January 31. Off Roi, at 6:51 a.m., Admiral Richard L. Conolly maneuvered his flagship

Maryland

to a position 2,000 yards off the northern beaches. That amounted to point-blank range for 16-inch gunsâor as Holland Smith put it, “So close that his guns almost poked their muzzles into Japanese positions.”

13

At precisely 7:15 a.m., the naval guns fell silent all at once, and the drone of carrier planes immediately filled the void. A precise airstrike followed, and as the planes flew away, the guns opened up again. A 127mm artillery emplacement on Roi fired gamely at the cruisers and destroyers offshore, but quickly attracted return fire that knocked it out of action. Truman Hedding recalled, “We learned a lot about softening up these islands before we sent the Marines in. We really worked that place over. They developed a tactic called the âSpruance haircut.' We just knocked everything down; there wasn't even a palm tree left.”

14

The islands in Kwajalein Atoll were struck by about 15,000 tons of bombs and naval shells in the seventy-two hours before H-Hour, amounting to more than a ton of ordnance for each man in the Japanese garrison. A wag on Turner's command ship adapted Winston Churchill's verdict on the Battle of Britain: “Never in the history of human conflict has so much been thrown by so many at so few.”

15

Transports carried nearly 64,000 troops of the 4th Marine Division and the Army's 7th Infantry Division. The first troop landings were to occur on several small islands adjoining Roi-Namur, designated

IVAN,

JACOB

,

ALLEN

,

ANDREW

,

ALBERT

, and

ABRAHAM

. Aerial photos had shown that they were either deserted or very lightly garrisoned, but if they contained any enemy artillery pieces, they might pose a threat to the landing boats. Once they had been secured, the marines would set up artillery batteries to direct fire onto the fortified beaches of Roi-Namur.

H-Hour for the landings on

IVAN

and

JACOB

had been set for 9:00 a.m., but choppy seas and a stiff breeze made for a difficult transfer into the amtracs. Once in the boats, marines were tossed cruelly on the swells and soaked to the skin by heavy salt spray. The inexperienced navy crews struggled to keep the boats in formation. With their radios drenched and

unusable, orders had to be passed verbally from boat to boat. Delays inevitably followed. At 9:30, the first boats churned in toward the beaches. Carrier planes dived low to bomb and strafe the Japanese firing positions. The boats destined for

IVAN

, battling heavy waves and winds, had to slow their speed to navigate through uncharted reefs. Several of the first-wave amtracs turned away from their assigned landing beaches on the ocean-facing side, and instead went around the island and put ashore on the lagoon beaches. This improvised landing succeeded, as the handful of Japanese defenders could not move into new positions quickly enough to counter it. From their beachhead, small groups of marines quickly overran the island and declared it secure at 11:00.

In the early afternoon, troops went ashore on the little islands

ALLEN

,

ALBERT

, and

ABRAHAM

, all to the east of Roi-Namur. As they raced into the beaches, the Higgins boats and LVTs fired bow-mounted machine guns and rockets and destroyed many of the Japanese guns. Having circled offshore for hours, many wet and seasick marines were relieved to stagger ashore, even if greeted with a hail of enemy fire. In most cases, on these secondary islands, effective fire support, air support, and the not-inconsiderable firepower mounted on the landing craft forced the small Japanese garrisons to keep their heads down, facilitating a bloodless landing.

ALBERT

was secured at 3:42,

ALLEN

by 4:28, and

ANDREW

(where there were no defenders at all) by 3:45.

ABRAHAM

, where only six Japanese soldiers were found, was secured by nightfall. American casualties had been minimal. That night, howitzers were hauled ashore and positioned to lay down fire on the fortified beaches of Roi and Namur.

The snafus encountered on D-Day were manageable, and none had been entirely unanticipated. “The Commanding General and Staff of the Northern Landing Force were well aware that things might not go as planned on D-Day,” General Schmidt's chief of staff later observed.

16

But the morning had witnessed a general breakdown in the command and control of landing craft. Admiral Conolly attributed the problem to the inexperience of the boat crews and a dearth of pre-landing rehearsals, exacerbated by rough weather and the loss of radios to water damage. For all of that, the admiral proudly concluded, “the plans were made to work and that is the final test of a command and its organization.”

17

The bulk of the 4th Marine Division was to storm the lagoon-side beaches of Roi and Namur at dawn on February 1. All would land in amtracs.

In order to avoid the confusion and disorder of Tarawa, the first two waves would climb into the amtracs while the vehicles were still embarked on the LST tank carriers. According to the operations plan, the amtracs would roll down the ramps and launch some miles offshore. Then they would enter the lagoon by the channel east of Namur and rendezvous off the landing beaches. But the little landing craft had labored mightily in the heavy seas offshore on D-Day, so Admiral Conolly decided to take the LSTs into the lagoon before dawn and launch the boats much closer to the beaches.

Covered by the big guns of the battleship

Tennessee

and other fire support ships, the tank carriers entered the lagoon at dawn. Carrier airstrikes and marine artillery on the adjoining islands added to the toll of misery inflicted on the defenders. The volume of fire from Japanese positions on both Roi and Namur had slackened considerably since the previous day. The bombardment of Roi, delayed by the passage of LSTs between the support units and the island, began at 7:10 a.m. The scheduled landing, designated “W-Hour,” was set for 10:00.

Getting the amtracs off the LSTs was not nearly as straightforward as had been anticipated. Those on the upper decks had to be lowered by elevators to the tank decks, but in a nasty twist, it turned out that the second-generation amtracs (“LVT-2s”) were too long to fit in the elevators. They had to be moved onto an inclined ramp, and even then they fit by just inches. Each machine had to be maneuvered just so, and delays unavoidably ensued. A malfunctioning elevator on one LST stranded nine amtracs on the weather deck. At 8:53 p.m., bowing to the inevitable, Conolly pushed W-Hour back to 11:00 a.m.

At 11:12, a signal dropped from the destroyer

Phelps

, sending the first waves of landing boats toward Roi. It was a thirty-minute run into the Red beaches. The naval barrage rose to a crescendo, and the air coordinator held the Avengers and Hellcats to above 2,000 feet so they could continue to bomb the islands while the naval guns were pouring shells into it. The simultaneous air and naval bombardment during the approach of the first wave was judged a great success, and similar tactics were to be employed in later amphibious operations.

The planes and naval guns desisted with exact timing as the first boats scraped ashore. The treads of the LVTs bit into the sand and drove up the beaches, firing their machine guns and rockets at enemy positions. The

first waves hit Namur about fifteen minutes later. Four battalions were put ashore on the two connected islands before noon.

Roi was a relative cakewalk. Wendy Point, the island's western extremity, was swiftly overrun by armored amtracs. The marines found that many of the pillboxes and defensive entrenchments had been blasted to rubble by the heavy bombing and bombardment. Japanese defenders seemed stupefied by the mighty shelling and did not fight with their usual ferocity. The landscape had been so drastically chewed up by naval shelling and bombing that many landmarks identified on the maps were no longer there. Infantry units could not be sure exactly where they were, relative to their assigned

targets, so they instinctively kept advancing toward the northern beaches. A few high-spirited companies had to be summoned back to the island's midsection so that the advance could proceed in order.