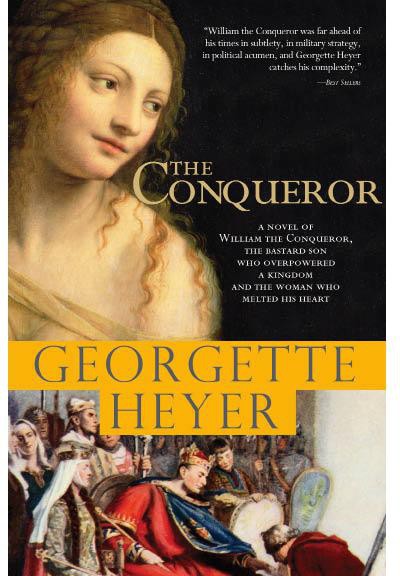

The Conqueror

Authors: Georgette Heyer

Copyright © 1931 by Georgette Heyer

Cover and internal design © 2008 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover photo © Bridgeman Art Library

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Heyer, Georgette, 1902-1974.

The conqueror / Georgette Heyer.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-1355-7

ISBN-10: 1-4022-1355-7

1. William I, King of England, 1027 or 8-1087—Fiction. 2. Great Britain—Kings and rulers—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6015.E795C66 2008

823’.912—dc22

2008017993

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

VP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Carola Lenanton

In friendship and in appreciationof her own incomparable workdone in the historic mannerdear to us both.

Prologue

(1028)

‘He is little but he will grow.’

Saying of Duke Robert of Normandy

There was so much noise in the market-place, such a hubbub of shouting and chaffering, that Herleva dragged herself to the window of her chamber and stood peeping down through the willow-slats that made a lattice over the opening. Market days brought a mob of people to Falaise from all the neighbouring countryside. There were franklins with slaves driving in the swine and cattle for sale; serfs with eggs and furmage spread on cloths upon the ground; great men’s stewards and men-at-arms; knights’ ladies on ambling palfreys; burghers from the town; and young maidens in troops of four or five together with little spending-silver in their purses, but full of exclamations for every novelty that met their eyes.

Wandering pedlars with their pack-horses had tempting wares to show: brooches of amethyst and garnet; bone combs; and silver mirrors burnished until one might see one’s face in them as clearly as in the beck that ran below the Castle. There were stalls piled high with candles, and oil, and smear; others with spices from the East spreading an aromatic scent: galingale, cloves, cubebs, and sweet canelle. Hard by, the food-merchants had set up their shelds, and here could be bought lampreys and herrings, fresh caught; such rare stores as ginger, and sugar, and pepper; jars of Lombard mustard; and loaves of wastel-bread, each one bearing the baker’s seal. Beyond these a chapman with copper-pots, and chargeours for the table plied a brisk trade among the housewives; while near at hand an apothecary tried to catch the women’s attention with his salves for bruises, his dragon’s water, and angelica-root, and even, slyly whispered, his love-philtres. His mild voice was drowned by the shouts of his neighbour, who spread length upon length of falding and sendal over his stall, and bade every passer-by see and feel his fine cloths.

But the crowd was thickest round the foreign pedlars, who had stranger merchandise to offer. There was jet brought from outremer which would drive away serpents if one heated it; finer cloth than falding held up by the Frisian merchants; cunningly wrought cups and jewels shown by dark Byzantines; orfrey, embroidered by Saxon women in England; and any number of trinkets, and ribands for the binding of one’s hair.

As she caught sight of one of these bunches, invitingly held up to a knot of maids below her window, Herleva lifted the heavy plait that lay over her shoulder, wondering whether a scarlet riband would look well twisted round it, and whether my lord Robert would think her pretty decked out in red. But nobody, not even so hot a lover as my lord Count, could think her pretty just now, she reflected. She was heavy with child, very near her time, and my lord Count was away in Rouen, waiting upon the pleasure of his father, good Duke Richard of Normandy. She wished that her pains might start, and the birth be soon over, so that she might ride up the steep hill again to the Castle that crowned one of its crags, and call upon the men-at-arms to open: open to Herleva the Beautiful, daughter of Fulbert, burgess of Falaise, and mistress of my lord Count of Hiesmes. Involuntarily her eyes turned towards the Castle, which she could just see, high above the squat wooden houses of the town and half-hidden by the trees that climbed its hill.

She thrust out her lower lip a little, picturing to herself the haute ladies of the Court at Rouen. She felt ill-used, and had begun to dwell upon her fancied wrongs, when her attention was diverted by a troop of minstrels who had begun to play quite near the house. They had come to the market on the chance of a few coins from the younger and lighter-hearted of the crowd, and perhaps a bite of supper afterwards in one of the rich burgher’s halls. The harper started to sing a popular chanson, while the juggler in his train cast up plates and balls into the air, and caught them all one after the other, faster and faster, until Herleva’s eyes grew round with wonder.

From the window Herleva could see her father Fulbert’s sheld, with the furs hanging up in it, and her brother Walter haggling with a burgher over the price of a fine rug of marten-skins. Close beside was a chapman who held up trinkets before the eyes of several envious maidens. If Count Robert had been there he would have bought his love the bracelet of hammered gold which the pedlar kept on showing, thought Herleva.

The remembrance of my lord Count made her discontented, and she moved away from the window, already weary of the bustle below it.

At the far end of the room a wooden door gave directly on to the twisting stair that led down to the hall, the principal dwelling-place of the house. No doubt her mother was busy preparing supper for Fulbert and Walter, but Herleva had no mind to go down to help her. The mistress of the son of the Duke of Normandy, she thought, had nothing to do with cooking-pots and greasy patins.

She crossed the floor with lagging steps, pushing the rushes with her feet, and laid herself down on the bed of skins against the wall. It was a bed for a Duchess, truly, made of good wood, and covered over with a bearskin which Fulbert had said grudgingly was more fit for Count Robert than for his

mie.

Herleva snuggled her cheek into the long fur, and smoothed it with her little hot hand, thinking of Count Robert, and how he called her, in his extravagant way, his princess.

Outside the sun was sinking slowly behind the heaths that lay beyond the town. A beam of gold came in through the willow-lattice, and struck the foot of the bed, making the brown hairs of the bearskin glint to an auburn glow. The hum of chatter, and the noise of the horses’ hooves, the occasional sharp sound of a voice raised above the general hubbub still continued in the market-place, but it had grown less with the sinking of the sun, and would soon cease altogether. Peasants from outlying villages were departing already from Falaise to reach home in the safe daylight; the chapmen were packing their bundles; and a stream of mules and sumpters was wending its way under the window towards the gates of the town.

The measured clop of the hooves made Herleva drowsy; she presently closed her eyes, and after some restless twisting and turning upon the bed, dropped off into an uneasy slumber.

Gradually the shaft of sunshine disappeared, and with the deepening of the shadows the noise in the market-place died away. The last pack-horse was led slowly past the house; and the merchants who lived within the town were all busy fastening up their shutters, and comparing each his day’s fortune with his neighbours’.

The light faded quite away; the cool of the evening stole into the chamber; Herleva shivered and moaned in her sleep, troubled by strange dreams.

She dreamed that as she lay a tree grew up out of her womb, spreading steadily till it became a giant among trees, with great branches stretched out like grasping arms. Then she perceived, in her dream, that Normandy lay before her gaze, even to the remotest corner of the Côtentin, and the far outpost of Eu. She saw the grey, tumbling sea, and was afraid, and cried out. The cry was muffled in her sleep, but beads of sweat started on her brow. Land lay beyond the sea; she saw it plainly, and knew it for England. And while she lay sweating in a strange terror she saw that the branches of the tree stretched out further and further till they over-shadowed both England and Normandy.

She screamed, and started up on the bed, pressing her hands to her eyes. Her face was wet with her fright; she wiped away the sweat with her fingers, and dared at last, as she realized that she had awakened from a nightmare, to look about her.

Her mother, Duxia, was standing in the doorway with a rushlight in her hand. ‘That was a great shout I heard you make,’ she said. ‘I thought the pains had come upon you, and here I find you sleeping.’

Herleva found that she was very cold. She pulled up the bearskin round her shoulders, and looked at Duxia in a boding way. She said in a low voice: – ‘I dreamed that a tree grew up out of my womb, mother, and no babe.’

‘Yes, yes,’ Duxia replied, ‘we have all our fancies at these times, daughter.’

Herleva clasped the bearskin closer round her, with her hands crossed between her breasts. ‘And as I lay,’ she said in a hushed voice, ‘I saw two countries spread before me, and these were our land of Normandy in all its might, and the land of the English Saxons, over the grey water.’ She let go one hand from the bearskin and pointed where she thought England might be. The bearskin slipped back from her shoulders, but she seemed no longer to feel the chill in her flesh. She fixed her eyes upon Duxia, and in the flickering rushlight they glowed queerly. ‘And the tree of my womb put forth huge branches that were as hands that would seize and hold fast, and these stretched out on either side me till Normandy and England both lay beneath them, cowering in their shadow.’

Duxia said: ‘Well, that’s a strange dream indeed, but meanwhile here is your father sitting down to his supper, and if you don’t bestir yourself the pottage will be cold before you come to it.’

But Herleva still sat motionless upon the bed, and Duxia, coming further into the room, perceived that she had a strange look in her face as of one who sees

marvels beyond ordinary folks’ vision. She laid her hands suddenly about her middle and said in a voice that had grown strong and clear: ‘My son will be a King. He shall grasp and hold, and he shall rule over Normandy and England, even as the tree stretched out its branches.’

This seemed a great piece of nonsense to Duxia. She was just about to make some soothing remark when Herleva gave a cry of pain, and straightened her body, with her muscles stiff to meet the sudden hurt.

‘Mother! Mother!’

Duxia began to bustle about her daughter at that, and both of them forgot all about the dream and its meaning. ‘There, child, that is nothing. You will have worse pain before you are better,’ Duxia said. ‘We will send out to summon our neighbour Emma, for she’s a rare one at a lying-in, and I warrant has helped more babes into the world than you will ever bear. Lie still; there is time enough yet.’

She had no leisure to think any more about Herleva’s prophecy, for Fulbert was calling for the boiled meats downstairs, and at the same time Herleva was clinging to her with both hands, very much afraid, and expecting every moment to undergo another such agony. Duxia found that she had her hands full for the next hour, but presently Emma came into the hall, and after she had seen Herleva and said that they might look for nothing for some hours yet, she helped Duxia clear away the dirty platters from the table, and directed the serfs how they should place the straw and the skins for the master’s bed.

Fulbert was fond of Herleva, but he was a sensible man, and he had a hard day’s work before him on the morrow, so that he thought he would be a great fool if he lost his sleep for nothing more serious than a lying-in. Moreover, he had never quite liked his daughter’s position, and though none of the neighbours considered it anything but an honour for Herleva to be the mistress of so puissant a seigneur as my lord Count of Hiesmes, he still could not feel at ease about it. As he made himself ready for the night, he felt that he would have been better pleased if the child to be born had been the lawful son of an honest burgher instead of a noble bastard.

When everything was set in order in the hall, and all the household disposed round the master for sleep, Duxia and Emma went off up the stairs to the room where Herleva lay whimpering upon her fine bedstead.

Emma was the wisest woman in Falaise. She knew the signs of the stars, and she could read omens, and foretell great happenings, so that presently as the two women sat on stools by a small brazier of charcoal Duxia was minded to tell her of Herleva’s dream. The two coiffed heads drew close together, and the red glow from the brazier showed the lined faces intent and knowing. Emma nodded, and clicked her tongue in her cheek. It was very likely, she said, and she went on to tell Duxia of other such visions which she had seen happily fulfilled.

An hour after midnight the child was born. A cock in some shed not far away, perhaps catching sight of a star through a chink in the door, crowed once, and then was silent.

There was a pallet of straw in a corner of the room near the brazier. Emma wrapped the babe loosely round in a cloth and laid him down upon this pallet, where he would be safe while she turned back to Herleva. When Duxia presently went to pick up the child she found that he had thrust his arms from out of the cloth, and was clutching the straw on which he lay in both his fists. She was glad to see that he was so lusty an infant, and called to Emma to admire his strength. Perhaps the prophecy was running in Emma’s head, or perhaps she had never seen a newborn child so vigorous. ‘Mark what I say, Duxia!’ she exclaimed, ‘that child will be a great prince. See how he takes seisin of the world! He’ll grasp everything that comes in his way and out of it, you see if he doesn’t.’

Her words reached Herleva, who seemed to herself to be sinking leagues deep into a heavy swoon. She said faintly: ‘He will be a King.’

As soon as she was well enough to think and plan again Herleva sent for Walter, and insisted that he should ride to Rouen to tell the Count of the birth of his son. Walter was too fond of her to resent her imperious ways, but Fulbert, who needed him to dress a couple of otter-skins, thought it a great�piece of nonsense, and was very near to forbidding him to�go.

When Walter came back from Rouen Herleva was up and about again, and he had scarcely set foot inside the hall when she pounced on him, asking a dozen questions at once, and wondering how he could have been away so long.

‘It was not easy to come at my lord Count,’ Walter explained, in his patient way. ‘There are so many great seigneurs about him in the Castle at Rouen, and the pages would not let me pass the doors.’