The Cost of Courage (23 page)

Read The Cost of Courage Online

Authors: Charles Kaiser

AT THE BEGINNING OF

1945, the sisters still don’t know any of this. Jacqueline decides to go to Switzerland, to see if there might be a way to ransom the freedom of the rest of the family. Her trip is a failure: She learns nothing about her parents or her brothers. When she returns to Paris, she tells her sister there is only an infinitesimal chance that any of them will survive.

Christiane briefly gets a job as the secretary for the Canadian ambassador to Paris, but the position is a poor fit. Christiane doesn’t even know how to type, and she doesn’t last there very long. Jacqueline goes to work for the Bureau Central de Renseignements et d’Action, the same organization André had been assigned to when he was de Gaulle’s military delegate in occupied Paris.

The sisters enjoy going out with the American and Canadian troops who are now crowding the city. They take them to dinner at their mess, which has much better food than what is available to most Parisian civilians. The Occupation is over, but most store shelves remain empty.

At the same time, the sisters are very much aware of the Battle of the Bulge, the last major German counteroffensive, and the greatest surprise attack on American forces after Pearl Harbor. It begins in the middle of December 1944 in the Ardennes region of Belgium, France, and Luxembourg.

On December 16, two hundred thousand soldiers from three German armies suddenly launch themselves against the Allies. There has been a serious Allied intelligence failure — the day before the attack, British field marshal Montgomery promised Eisenhower that the Germans cannot “stage major offensive operations.” Just as the Germans had partly ignored the explicit BBC warning of the impending invasion at Normandy, Allied intelligence officers had discounted the information from four captured German POWs, who had warned of a pre-Christmas offensive.

The German thrust is forty miles wide and fifty-five miles deep into the Allied line, creating a shape on the map that gave the battle its enduring name. On December 19, the 5th Panzer Army surrounds the American 106th Division in the center of the offensive at St. Vith, and forces eight thousand American soldiers to surrender — the largest defeat of American troops since the Civil War.

As the weather slowly improves, the Allies’ overwhelming air superiority gradually reasserts itself, the Germans begin to run out of gasoline, and the systematic destruction of railroad lines makes it impossible to bring a single German train across the Rhine. When the battle finally ends in the fourth week of January, the Germans have lost 120,000 men killed, wounded, captured, or missing, while the Americans have suffered 19,000 killed, 48,000 wounded, and 21,000 captured or missing. “The great difference,” wrote Andrew Roberts, “was that in material the Allies could make up these large losses, whereas the Germans no longer could.”

In the end, the Ardennes offensive weakens the remaining German troops so much that its biggest effect is to hasten the progress of the Russian advance from the east.

IT IS

APRIL

1945 before Jacqueline and Christiane receive confirmation of the first of three catastrophes. They are at lunch at the home of their aunt Ginette — the same aunt who had sent her maid into the street to intercept Christiane and save her life, hours after her parents had been arrested. The telephone rings, and they learn officially that their mother is dead. A short time later, they are notified of their father’s death. But they still have no news of either of their brothers.

Two weeks later, Adolf Hitler, the father of all of Europe’s agony, summons his longtime mistress, Eva Braun, to his underground bunker in Berlin. He marries her on April 29. At three thirty the following afternoon, Hitler shoots himself in the mouth with a revolver, and Braun — his wife of forty hours — swallows poison. Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, is the last of his top collaborators to remain in the bunker with the Führer as the Russians swarm over Berlin. The day after Hitler dies, Goebbels and his wife poison their six children inside the bunker. Then they both commit suicide.

Mussolini and his mistress are caught by Italian partisans on April 26 while trying to escape into Switzerland. They are executed two days later and then strung up by their feet from lampposts in Milan. On April 29, the Germans sign an unconditional surrender of Italy and southern Austria; it takes effect on May 2, removing one million German troops from the conflict.

In Nuremberg, the site of gigantic Nazi rallies in the 1930s, American troops replace “Adolf-Hitler-Str.” signs with new ones reading “Roosevelt Blvd.” Then they blow up the huge stone swastika atop the Nuremberg stadium.

On May 5, Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg, the new commander in chief of the German Navy, arrives in Reims, in northeastern France, where Eisenhower has established his headquarters. Two days later, at three forty-one in the morning, Germany surrenders

unconditionally. At midnight on May 8, the guns stop firing and the bombs stop falling all across Europe. The “Thousand-Year Reich” is finally extinguished, after twelve years, four months, and eight days of mayhem, perversity, destruction, and death.

A FEW DAYS BEFORE

the surrender is signed ending the war in Europe, Christiane and Jacqueline get a terrible scare. The doorbell rings at their parents’ apartment. It is Gilbert Farges, one of the men who had shielded André on the train when he was deported to Auschwitz. When he introduces himself — “I was deported with your brother André” — the sisters are sure he is there to announce André’s death. But Farges immediately adds that their brother is still alive — the first genuinely good news they have had in 1945.

Unlike the other members of his family sent to the camps, André has a vital cadre of friends at Flossenbürg. Somehow, everyone who survives with him is equipped with “the intimate conviction that we would still be alive after the war,” remembered his friend Michel Bommelaer. “Among us, there was always a faithfully burning pocket of joy and hope.”

André’s most extraordinary morale booster for Michel, his fellow piano player, is to teach him “the Schumann piano concerto, certain Beethoven sonatas, and the Brandenburg Concertos” — all without a piano, of course. “In this way he shared a small piece of his very tender heart, his determination to fight,” and his belief — remarkable, under the circumstances — in the “intellectual quest of a humanity that, no matter what, had a chance to better itself.”

Gilbert Farges said, “Survival was a constant act of will and dignity. André applied himself with discipline, determination, and a ferocious courage at all moments. The influence of his example surely saved the lives of a number of his companions. This period of his existence tempered his character — tempered it the way one used to temper a sword in an earlier era.”

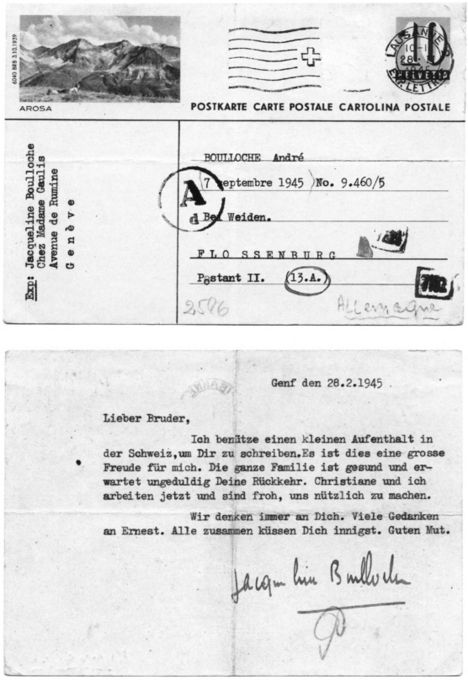

A postcard Jacqueline wrote to André in German at the beginning of 1945, when he was still a prisoner at Flossenbürg.(

photo credit 1.16

)

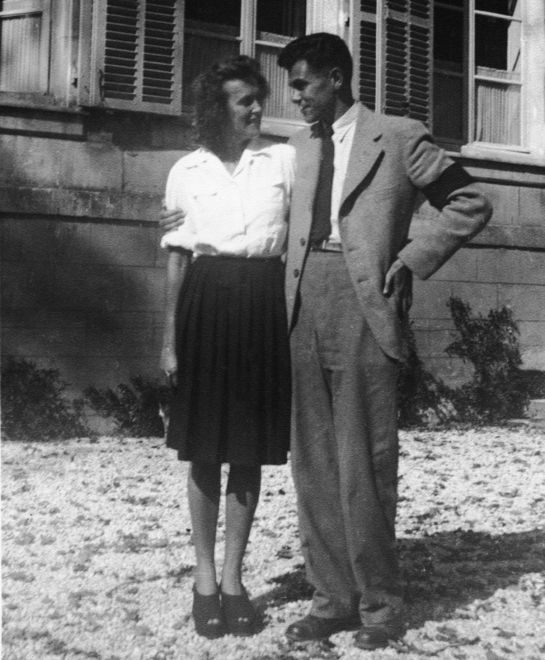

André Boulloche in the summer of 1945, immediately after his return to Paris from three German concentration camps.(

photo credit 1.17

)

IT WILL REQUIRE

one more miracle for André to return to his sisters’ arms alive. At dawn on April 16, 1945, at an altitude of twenty-five hundred feet, the camp at Flossenbürg is bathed in “a pure and wonderfully soft light,” Georges d’Argenlieu remembered. The sounds of American guns can be heard in the distance. And suddenly all the SS guards leave the camp.

“We had been saved!” d’Argenlieu exulted. “There will be no evacuation! Fourteen thousand deportees with no strength lay extended, offering their bodies to the rays of this first sun of resurrection.” The sounds of American guns grow closer: ten miles, then seven miles away. But when the sun goes down that night, the SS returns, heaving everyone “back into the void.”

“On April 20th, the sinister evacuation — the one we had so rejoiced at escaping — begins,” d’Argenlieu continued. “Fourteen thousand leave the camp in five hours. Their rescue by the Americans is three days and eighty miles away. The six thousand who succumb on the road will never know that minute.”

Through a final stroke of good fortune, André Boulloche, Charles Gimpel, Henri Lerognon, another alumnus of the Ecole polytechnique, and Georges d’Argenlieu manage to slip into the typhoid ward of the camp at the moment of the evacuation. That is the only way they can avoid the death march. Three days later, on April 23, a unit of George Patton’s army finally arrives to liberate the camp.

IN THE CHAOS

following the liberation, it takes André nearly four weeks to make his way back to Paris, a fearfully gaunt figure with the bulging eyes of a camp survivor. On May 19, he finally enters the lobby of his parents’ apartment building on avenue d’Eylau. The concierge recognizes the ravaged twenty-nine-year-old as he walks in the front door. As André gets on the elevator, the concierge sprints up the stairs to warn his sisters that their brother has come home.

“Of course he was extremely thin,” Christiane remembered. “But what was worse was the horrible look in his eyes.” The sisters have agreed that Christiane will deliver the terrible news about their parents when André gets there. “But, when he was finally standing there before us,” Christiane remembered, “with that ghastly appearance that all the deportees had, I could not utter a word.”

When she finally gathers her strength to tell him what has happened, this is his immediate reply: “If I’d known that, I would not have come back. I would have died in the camps.” When they tell him which camp Robert has been sent to, André says there is very little chance that he has survived there.

A couple of weeks after André’s return, they are officially notified that Robert died at Ellrich, on January 20, 1945.

*

During the time General Choltitz was a prisoner of the Allies, he declared, “I’m saying that we steal! We collect the stuff up into stores, like proper robbers … that’s the frightful part of it. This revolting business of engaging in organized robbery of private property … Throughout the whole of France … Whole train-loads of the most beautiful antique furniture from private houses! It’s frightful; it’s an indescribable disgrace!” (Neitzel,

Tapping Hitler’s Generals

)

My deportation to the camps is very largely what made me what I am today. And it was the war that led me to socialism. I am a man who engages in life — who feels the necessity to engage.

— André Boulloche

André Boulloche had the longest service in the Resistance, the most audacious, the most important and the most challenging.

— André Postel-Vinay

“Did your father André ever talk about the war?”

“Once, perhaps. But he didn’t have to talk about it. It was always there. It’s as if you said we’re going to talk about the fact that the walls are white. Obviously they’re white! You’re not going to talk about them, because they’re there, all the time.”

— Agnès Boulloche

T

HE THREE SURVIVORS

chose very different paths to salvation when the war was over. Christiane and Jacqueline “turned the page” by getting married

*

and having children — and by never discussing the war with each other, or almost anyone else, for fifty years. Jacqueline and Alex Katlama were the first to marry, in the summer of 1945, shortly after André’s return from the camps.