The Crimean War (45 page)

Authors: Orlando Figes

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Europe, #Other, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Crimean War; 1853-1856

Compared to the French, the British ate badly, although – to begin with – there were plentiful supplies of meat and rum. ‘Dear wife,’ wrote Charles Branton, a semi-literate gunner in the 12th Battalion Royal Artillery on 21 October, ‘we have lost many lives through the Corora they are dying like rotten sheep but we have plenty to eat and drink. We have two Gills of rum a day plenty of salt por and a pound and a ½ of biskit and I can ashore you that if we had 4 Gills of rum it would be a godsend.’ As autumn gave way to winter, the supply system struggled to keep going on the muddy track from Balaklava to the British camp, and the rations steadily declined. By mid-December there was no fruit or vegetable in any form – only sometimes lemon or lime juice, which the men added to their tea and rum to prevent scurvy – although officers with private means could purchase cheese and hams, chocolates and cigars, wines, champagnes, in fact almost anything, including hampers by Fortnum & Mason, from the shops of Balaklava and Kadikoi. Thousands of soldiers became sick and died from illnesses, including cholera, which resurfaced with a vengeance. By January the British army could muster only 11,000 able-bodied men, less than half the number it had under arms two months before. Private John Pine of the Rifle Brigade had been suffering for several weeks from scurvy, dysentery and diarrhoea when he wrote to his father on 8 January:

We have been living on biscuit and salt rations the greater part of the time we have been in the field, now and then we get fresh beef and once or twice we have had mutton but it is wretched stuff not fit to throw to an English dog, but it is the best that is to be got out here so we must be thankful to God for that. Miriam [his sister] tells me there is a lot of German Sausages coming out for the troops. I wish they would make haste and send them for I really think I could manage a couple of pound at the present minute … . I have been literally starved this last 5 or six weeks … If my dear father you could manage to send me in the form of a letter a few anti-scorbutic powders I should be obliged to you for I am rather troubled with the scurvy and I will settle with you some other time please God spares me.

Pine’s condition worsened and he was shipped to the military hospital at Kulali near Constantinople, where he died within a month. Such was the chaos of the administration that there was no record of his death, and it was a year before his family found out what had happened from one his comrades.

16

16

It was not long before the British troops became thoroughly demoralized and began to criticize the military authorities. ‘Those out here are much in hope that peace will soon be proclaimed,’ Lieutenant Colonel Mundy of the 33rd Regiment wrote to his mother on 4 February. ‘It is all very fine for people at home talking of martial order and the like but

everyone

of us out here has had quite enough of hardship, of seeing our men dying by thousand from sheer neglect.’ Private Thomas Hagger, who arrived in late November with the reinforcements of the 23rd, wrote to his family:

everyone

of us out here has had quite enough of hardship, of seeing our men dying by thousand from sheer neglect.’ Private Thomas Hagger, who arrived in late November with the reinforcements of the 23rd, wrote to his family:

I am sorry to say that the men that was out before I came have not had so much as a clean shirt on for 2 Mounths the people at home think that the troops out hear are well provided for I am sorry to say that they are treated worse then dogs are at home I can tell the inhabitants of old England that if the solders that are out hear could but get home again they would not get them out so easy it is not the fear of fighting it is the worse treatment that we receive.

Others wrote to the newspapers to expose the army’s poor treatment. Colonel George Bell of the 1st (Royal) Regiment drafted a letter to

The Times

on 28 November:

The Times

on 28 November:

All the elements of destruction are against us, sickness & death, & nakedness, & uncertain ration of salt meat. Not a drop of Rum for two days, the only stand by to keep the soldier on his legs at all. If this fails we are done. The Communication to Balaklava impossible, knee deep all the way for 6 miles. Wheels can’t move, & the poor wretched starved baggage animals have not strength to wade through the mud without a load. Horses – cavalry, artillery, officers’ chargers & Baggage Animals die by the score every night at their peg from cold & starvation. Worse than this, the men are dropping down fearfully. I saw

nine

men of 1st Batt[alion] Royal Regt lying

Dead in one Tent

to day, and 15 more dying! All cases of Cholera … . The poor men’s backs are never dry, their one suit of rags hang in tatters about them, they go down to the Trenches at night wet to the skin, ly there in water, mud, & slush till morning, come back with cramps to a crowded Hosp[ital] Marquee tattered by the storm, ly down in a fetid atmosphere, quite enough of itself to breed contagion, & dy there in agony. This is no romance, it is my duty as a C.O. to see & Endeavour to alleviate the sufferings & privations of my humble but gallant comrades. I can’t do it, I have no power. Everything almost is wanting in this Hospital department, so badly put together from the start. No people complain so much of it as the Medical officers of Regts & many of the Staff doctors too.

At the end of his letter, which he finished the next day, Bell added a private note to the paper’s editor, inviting him to publish it and ending with the words: ‘I fear to state the real state of things here.’ A watered-down version of the letter (dated 12 December) was published in

The Times

on the 29th, but even that, Bell later thought, had been enough to ruin his career.

17

The Times

on the 29th, but even that, Bell later thought, had been enough to ruin his career.

17

It was through a report in

The Times

that the British public first became aware of the terrible conditions suffered by the wounded and the sick. On 12 October readers were startled by the news they took in over breakfast from

The Times

correspondent in Constantinople, Thomas Chenery, ‘that no sufficient medical preparations have been made for the proper care of the wounded’ who had been evacuated from the Crimea to the military hospital at Scutari, 500 kilometres away. ‘Not only are there not sufficient surgeons – that, it might be urged, was unavoidable – not only are there no dressers and nurses – that might be a defect of system for which no one is to blame – but what will be said when it is known that there is not even linen to make bandages for the wounded?’ An angry leader in

The Times

by John Delane, the paper’s editor, the next day sparked a rush of letters and donations, leading to the establishment of a

Times

Crimean Fund for the Relief of the Sick and Wounded by Sir Robert Peel, the son of the former Prime Minister. Many letters focused on the scandal that the army had no nurses in the Crimea – a shortcoming which various well-meaning women now proposed to remedy. Among them was Florence Nightingale, the unsalaried superintendent of the Hospital for Invalid Gentlewomen in Harley Street, a family friend of Sidney Herbert, Secretary at War. She wrote to Mrs Herbert offering to recruit a team of nurses for the East on the same day as her husband wrote to Nightingale asking her to do precisely that: the letters crossed each other in the post.

The Times

that the British public first became aware of the terrible conditions suffered by the wounded and the sick. On 12 October readers were startled by the news they took in over breakfast from

The Times

correspondent in Constantinople, Thomas Chenery, ‘that no sufficient medical preparations have been made for the proper care of the wounded’ who had been evacuated from the Crimea to the military hospital at Scutari, 500 kilometres away. ‘Not only are there not sufficient surgeons – that, it might be urged, was unavoidable – not only are there no dressers and nurses – that might be a defect of system for which no one is to blame – but what will be said when it is known that there is not even linen to make bandages for the wounded?’ An angry leader in

The Times

by John Delane, the paper’s editor, the next day sparked a rush of letters and donations, leading to the establishment of a

Times

Crimean Fund for the Relief of the Sick and Wounded by Sir Robert Peel, the son of the former Prime Minister. Many letters focused on the scandal that the army had no nurses in the Crimea – a shortcoming which various well-meaning women now proposed to remedy. Among them was Florence Nightingale, the unsalaried superintendent of the Hospital for Invalid Gentlewomen in Harley Street, a family friend of Sidney Herbert, Secretary at War. She wrote to Mrs Herbert offering to recruit a team of nurses for the East on the same day as her husband wrote to Nightingale asking her to do precisely that: the letters crossed each other in the post.

The British were far behind the French in their medical arrangements for the sick and wounded. Visitors to the French military hospitals in the Crimea and Constantinople were impressed by their cleanliness and good order. There were teams of nurses, mostly nuns recruited from the Order of St Vincent de Paul, operating under instructions from the doctors. ‘We found things here in far better condition than at Scutari,’ wrote one English visitor of the hospital in Constantinople:

There was more cleanliness, comfort and attention; the beds were nicer and better arranged. The ventilation was excellent, and, as far as we could see or learn, there was no want of anything. The chief custody of some of the more dangerously wounded was confided to Sisters of Charity, of which an order (St Vincent de Paul) is founded here. The courage, energy and patience of these excellent women are said to be beyond all praise. At Scutari all was dull and silent. Grim and terrible would be almost still better words. Here I saw all was life and gaiety. These were my old friends the French soldiers, playing at dominoes by their bed-sides, and twisting paper cigarettes or disputing together … I liked also to listen to the agreeable manner in which the doctor spoke to them. ‘Mon garçon’ or ‘mon brave’ quite lit up when he came near.

Captain Herbé was evacuated to the hospital later in the year. He described its regime in a letter to his family:

Chocolate in the morning, lunch at 10 o’clock, and dinner at 5. The doctor comes before 10 o’clock, with another round at 4. Here is this morning’s lunch menu:Très bon potage au tapioca

Côtelette de mouton jardinière

Volaille rotie

Pommes de terre roties

Vin de Bordeaux de bonne qualité en carafe

Raisins frais et biscuitsSeasoned by the sea wind that breezes through our large windows, this menu is, as you can imagine, very comforting, and should soon restore our health.

18

French death rates from wounds and diseases were considerably lower than British rates during the first winter of the war (but not the second, when French losses from disease were horrendous). Apart from the cleanliness of the French hospitals, the key factor was having treatment centres near the front and medical auxiliaries in every regiment, soldiers with first-aid training (

soldats panseurs

) who could help their wounded comrades in the field. The great mistake of the British was to transport most of their sick and wounded from the Crimea to Scutari – a long and uncomfortable journey on overcrowded transport ships that seldom had more than a couple of medical officers on board. Raglan had decided on this policy on purely military grounds (‘not to have the wounded in the way’) and would not listen to protests that the wounded and the sick were in no state to make such a long journey and needed treatment as soon as possible. On one ship,

Arthur the Great

, 384 wounded were laid out on the decks, packed as close as possible, much as it was on the slave ships, the dead and dying lying side by side with the wounded and the sick, without bedding, pillows or blankets, water bowls or bedpans, food or medicines, except those in the ship’s chest, which the captain would not allow to be used. Fearing the spread of cholera, the navy’s principal agent of transports, Captain Peter Christie, ordered all the stricken men to be put on board a single ship, the

Kangaroo

, which was able to accommodate, at best, 250 men, but by the time it was ready to sail for Scutari, perhaps 500 were packed on board. ‘A frightful scene presented itself, with the dead and dying, the sick and convalescent lying all together on the deck piled higgledy-piggledy,’ in the words of Henry Sylvester, a 23-year-old assistant surgeon and one of just two medical officers on the ship. The captain refused to put to sea with such an overcrowded ship, but eventually the

Kangaroo

sailed with almost 800 patients on board, though without Sylvester, who sailed for Scutari aboard the

Dunbar

. The death toll on these ships was appalling: on the

Kangaroo

and

Arthur the Great

, there were forty-five deaths on board on each ship; on the

Caduceus

, one-third of the passengers died before they reached the hospitals of Scutari.

19

soldats panseurs

) who could help their wounded comrades in the field. The great mistake of the British was to transport most of their sick and wounded from the Crimea to Scutari – a long and uncomfortable journey on overcrowded transport ships that seldom had more than a couple of medical officers on board. Raglan had decided on this policy on purely military grounds (‘not to have the wounded in the way’) and would not listen to protests that the wounded and the sick were in no state to make such a long journey and needed treatment as soon as possible. On one ship,

Arthur the Great

, 384 wounded were laid out on the decks, packed as close as possible, much as it was on the slave ships, the dead and dying lying side by side with the wounded and the sick, without bedding, pillows or blankets, water bowls or bedpans, food or medicines, except those in the ship’s chest, which the captain would not allow to be used. Fearing the spread of cholera, the navy’s principal agent of transports, Captain Peter Christie, ordered all the stricken men to be put on board a single ship, the

Kangaroo

, which was able to accommodate, at best, 250 men, but by the time it was ready to sail for Scutari, perhaps 500 were packed on board. ‘A frightful scene presented itself, with the dead and dying, the sick and convalescent lying all together on the deck piled higgledy-piggledy,’ in the words of Henry Sylvester, a 23-year-old assistant surgeon and one of just two medical officers on the ship. The captain refused to put to sea with such an overcrowded ship, but eventually the

Kangaroo

sailed with almost 800 patients on board, though without Sylvester, who sailed for Scutari aboard the

Dunbar

. The death toll on these ships was appalling: on the

Kangaroo

and

Arthur the Great

, there were forty-five deaths on board on each ship; on the

Caduceus

, one-third of the passengers died before they reached the hospitals of Scutari.

19

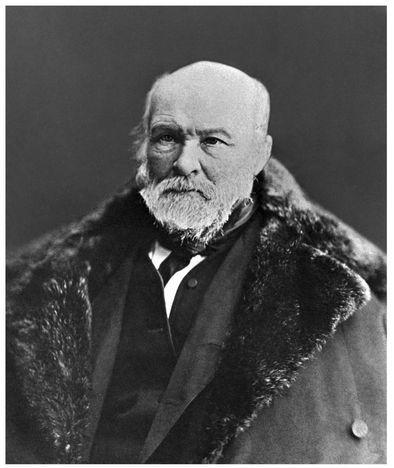

The Russians, too, understood the need to treat the wounded as soon as possible, although conditions in their hospitals were far worse than anything that Florence Nightingale would find in Scutari. Indeed, it was a Russian, Nikolai Pirogov, who pioneered the system of field surgery that other nations came to only in the First World War. Although little known outside Russia, where he is considered a national hero, Pirogov’s contribution to battlefield medicine is as significant as anything achieved by Florence Nightingale during the Crimean War, if not more so.

Nikolai Pirogov

Other books

Cinderella Screwed Me Over by Cindi Madsen

Sartor Resartus (Oxford World's Classics) by Carlyle, Thomas, Kerry McSweeney, Peter Sabor

How a Lady Weds a Rogue by Ashe, Katharine

Veil of Silence by K'Anne Meinel

The Lost Castle by Michael Pryor

Dorothy Eden by Eerie Nights in London

Honey & Ice by Dorothy F. Shaw

Wolves of Haven: Lone by Danae Ayusso

Starstruck - Book Two by Gemma Brooks

WindDeceiver by Charlotte Boyett-Compo