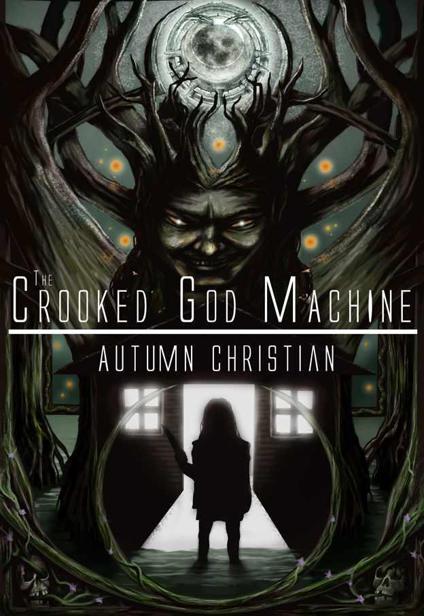

The Crooked God Machine

The Crooked God Machine

by Autumn Christian

The Crooked God Machine

Autumn Christian

Copyright 2011 by Autumn Christian

Kindle Edition

Acknowledgements

For all the Christians

Table of Contents

The Crooked God Machine

Copyright 2011 by Autumn Christian

Part One

Part Two: Seven Years Later

Part Three

Part One

Chapter One

Before Daddy started stuffing road kill in the living room, I almost thought everything would turn out all right.

My Daddy’s hands were like burnt maps. He said if we wanted to learn how to conquer the world, all we had to do was look at his hands. After working at the factory he used to sit at the kitchen table with a glass of whiskey and the after dinner cigar that Momma always gave him. He kicked off his boots and lit the cigar and said, “Hey kids, you want to hear a story?” Then he’d lay those black scarred hands, palms up, on the kitchen table for us to touch. I still remember their texture, like cool braised metal.

When Sissy and I were small and baby brother hadn’t yet started to eat his fingers Daddy picked us up and held us above his head so we could fly. He had an indomitable body that seemed to be the only support that kept our rickety, dark-creak house from falling into the swamp. He filled every room he entered to full capacity. I can still see the mark above the kitchen door where he once hit his head.

Daddy let the sun into the house. He pulled back the curtains, opened the windows, turned on the lights. He said there were too many dark corners in that house to hide in. He said there were too many dark corners in the universe. He made Momma pretty by throwing the sunlight in her hair like seeds. I never saw Daddy kiss her, but he danced with her across the living room floor. He chased Momma out onto the porch so that the sunlight jumped off her skin. That was the only time I ever heard her laugh, when Daddy brought her the sun.

When Daddy was here Sissy still wore her Sunday dresses and called me Bubba instead of Charles. She still let me hide inside her coat when the black moon cast its bad shadow across the house and the plague machines beat against the air with their chuk-chuk-chuk noises. I curled up against her ribcage and tried to guess how many birds could hide inside her bones, and she whispered, “shhh,” and told me morning would come soon.

“I’ll tell you everything you need to know for a glass of lemonade,” he told Sissy when she wanted to learn how to plant a garden. Then he’d instruct her how to plant the basil and the hyacinth and the tomatoes as he read the newspaper on the front porch. The tomatoes never grew, but the hyacinth flourished. He promised the tomatoes would come in next year, as if he owned the weather.

And when I sat outside with my sketchbook and charcoals trying to draw landscapes, grinding my nails down to the nub because none of my sketches came out right, he was the one who sat down beside me and put his arm around my shoulder and told me to stop looking down at the paper.

“Before you can become an artist, you have to be a scientist,” he said, “Look out into the swamp and draw what you see. Not what you think you see.”

But then one day Daddy came home from work early. He slammed the front door open with a crack and stood there for a moment, heaving. Then he lurched forward so fast I thought his head might roll off his shoulders and across the carpet. Then without speaking to any of us, he crossed the living room floor and sat down on the couch. He took off his steel-toed work boots with heavy, slow motions like he was sinking underwater. Momma handed my baby brother to Sissy. Momma got up and got one of Daddy’s cigars, but he declined to take it.

Finally he got his boots off and set them down and spoke to the wall.

“The factory shut down,” he told Momma.

“What are we going to do?”

“Nothing to do,” he said.

He took the cigar from Momma, handling it like a live animal. He lit it and breathed deep and his face turned slack like a snapped belt. That’s when it seemed as if the house around us shifted, grew darker, as if Daddy’s protection against the shadows had finally been broken, and they now insinuated themselves through the crevices in the floor. My baby brother cried out. Sissy rocked him with mechanical motions. Momma stared at the hard space beyond Daddy’s head.

After dinner Daddy put back on his boots with the same underwater heaviness that he’d taken them off. It was night time now, brighter than I’d ever remembered before, with the stars cracking open and the trees in the woodland swamp festering with color like fresh wounds.

“You shouldn’t go out there tonight,” Momma said as he started lacing his boots, “The hell shuttles are out again. Not to mention the monsters.”

Daddy went to where my baby brother lay asleep in his crib in the corner of the kitchen. He lingered for a moment with his scarred hands on the railing, before leaning over and kissing him on the forehead.

“Don’t you worry about a thing,” Daddy said, to no one in particular. Then he left the house.

I woke up in the middle of the night to Momma and Daddy screaming at each other in the kitchen downstairs. Momma’s voice was a runaway train, halting and crashing and squealing. Daddy’s voice was congealed thick, like syrup and glass. My baby brother wailed in their undercurrent, creating a wall of sound.

I got up from bed and went to the stairs. I found Sissy already there, standing on the first step in the last stretch of shadow beyond the kitchen light. Sissy craned her neck as she listened.

“Don’t go down there,” she said to me, “that’ll get you in trouble.”

I listened to them fight from the steps. Momma argued like all wives everywhere. You don’t love me anymore. Think of the children. You could’ve been killed. The shuttles are out and if the monsters find you then you’ll never walk right again. Daddy yelled as if he understood what Momma was talking about, but instead he talked about the anatomy of plague machines. The monster he’d heard singing out in the swamp. Fire that grew out of God’s head. The memories that had followed him for years, wraith memories of dead friends and cancelled television shows.

“I’ll leave you if you go out there again,” Momma finally said.

Daddy laughed. No, not an ordinary laugh. A sudden pop, a wet bone crunch of a laugh.

“Where are you going to go?” he asked, “You’ve never been outside Edgewater. You’ll be so lost you’ll fall off the edge of the world.”

Daddy went out every night after that for the next week. Drinking with his ex-coworkers at the Legion, Sissy told me one day when Momma wasn’t around. Nothing left for any of us since the factory closed down except this house and this town that would probably soon collapse from underneath us.

One night Daddy came home with a bad back and a broken wrist. He took off his shirt in the living room and I saw from my hiding place at the top of the stairs the bite marks lacerated on his back. I saw the claw scratches like ribbons welded onto his ribcage. Momma and Sissy were asleep, bursting with dreams that made them occasionally cry out and shake. I was the only one who saw Daddy sit down on the couch in front of the television and bend over with his pearly bone exposed in his back, his back muscles masticating like a jaw every time he moved. He closed his eyes heavy and when he adjusted on the couch his wounds made a wet sound, a tearing sound, the sound of the earth disintegrating out from underneath me.

After that he stopped bringing us the sun. He no longer chased Momma out onto the porch or gave us his cool hands to touch and tell us stories of metal. He stopped teaching me how to draw, stopped explaining the anatomy of plants to Sissy, stopped tossing my baby brother up to the ceiling or kissing him while he slept. His silence ballooned upwards like a column of smoke.

He stopped going out drinking, but instead went out in the morning to scrape the dead animals off the side of the road. He took up taxidermy and gutted road kill on the coffee table in the living room while watching God on the television and smoking his cigars. The living room existed in a perpetual haze. Stuffed raccoons, badgers, and possums lined the shelves in every room.

Momma said all the smoke was bad for the baby, so she stayed upstairs and drew all the curtains down and rocked my baby brother while he cried and cried. Daddy just tapped his teeth with the tip of his gutting knife and then lit another cigar. He pulled down the windows and turned off all the lights in the house except the white work lamp he used for his taxidermy. While he worked his bad back cast a nightmare shape against the wall. His broken wrist swelled.

I remembered Sissy and I sat in the kitchen working on our homework one afternoon. I leaned back in my chair and looked into the adjacent living room to see Daddy hunched over a dead deer he'd thrown, legs up, on the coffee table.

Momma came down the stairs and walked past Daddy without acknowledging him. She came into the kitchen and fixed herself a hot cup of lavender tea. She leaned against the counter holding the tea, waiting for it to cool.

“Those blood stains are never going to come out of the coffee table,” she said, and shook her head.

I couldn't sleep that night because my baby brother kept crying. I went downstairs to get a glass of milk from the refrigerator and found Daddy still downstairs working on his dead deer. The television was on, and God in his black horned mask peered out at my Daddy as he worked. His skin glowed yellow sick underneath his work light. All of his cigars were lined up on the table by his right hand, so that whenever he smoked one down he could grab another. I glanced over at the clock. It was about 3:30 in the morning.