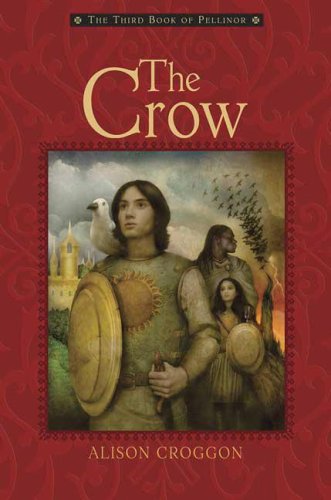

The Crow

Authors: Alison Croggon

THE CROW

Pellinor 03

By

Alison Croggon

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author's imagination or, if real, are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2006 by Alison Croggon

Maps drawn by Niroot Puttapipat

First U.S. paperback edition 2008

First published by Penguin Books, Australia

ISBN 978-0-7636-3409-4 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-7636-4146-7 (paperback)

Printed in the United States of America

Candlewick Press

2067 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, Massachusetts 02140

T

ABLE

O

F

C

ONTENTS

A Brief Introduction to the Suderain and Amdridh

One is the singer, hidden from sunlight

Two is the seeker, fleeing from shadows

Three is the journey, taken in danger

Four are the riddles, answered in treesong:

Earth, fire, water, air Spells you OUT!

— Traditional Annaren nursery rhyme Annaren Scrolls, Library of Busk

A Note On The Text

The Crow

is the third part of my translation of the eight-volume Annaren classic text, the

Naraudh Lar-Chane (The Riddle of the Treesong).

The enthusiastic response of readers so far confirm my initial instinct that this story could move outside the cloisters of academic study and fulfill its initial function. This we know quite clearly, from a note attributed to Cadvan of Lirigon, which is inscribed on a forepage to one of the extant versions: the purpose of the

Naraudh Lar-Chane

is, he says, to "delight all hearers" and to "introduce those unfamiliar with Bardic Lore to the ways and virtues of the Balance." Instruction, then, was important to those who wrote it down for their contemporaries; but its first intention was "delight."

As for "instruction": like the rest of the vast trove of parchment and reed-paper documents unearthed in Morocco in 1991 and known, misleadingly, as the Annaren Scrolls, this text repays study. It is one of the richest single sources for what we know of daily life in Edil-Amarandh, and gives us clear and vivid pictures of many of its peoples, from the complex Bardic cultures of the south to the various societies of the frozen plains of the north. It is quite likely that in its own time it served the same purpose as it does for us – that in part it was written to educate Annarens about the diversity of cultures amid which they lived. But unknown millennia later, this instruction has a special piquancy, bringing to life a civilization now long vanished from the face of the earth. The translation I present here cannot pretend to have captured in contemporary English all the subtleties and intricacies of the original text, and for this I am sorry; but I hope to have preserved at least some sense of its beauty and excitement. Those who wish to know more can find some sources of information in the appendices that I have included with each volume.

The first two volumes of Pellinor,

The Naming

and

The Riddle,

concern themselves with Maerad of Pellinor, a young Bard who discovers she is the Fated One prophesied to save her world from the rising darkness of the Nameless One.

The Naming

records her meeting with her mentor and friend, Cadvan of Lirigon, and their increasingly perilous journey to Norloch, the center of the Light in Annar, in order to reveal her destiny and bring her into the power of her Bardic Gift. In the course of her quest, by chance or fate, Maerad finds her brother, Cai of Pellinor, whom she had long thought dead, and also reveals the corruption that now lies at the heart of the Light in Annar.

The Riddle

traces her adventures with Cadvan as they flee the forces of both the Dark and the Light across the green lands of Annar and the frozen wastelands of the north, where she is captured by the Winterking, Arkan, a powerful Elemental being. The story finishes on Midwinter Day, after her escape from his northern stronghold, Arkan-da, and her discovery that the Treesong – or at least, half of it – is inscribed on the lyre that she inherited from her mother, and has owned since she was a child.

The Crow

– originally books IV and VI of the

Naraudh Lar-Chane –

shifts focus from Maerad's story to that of her brother Cai, known as Hem. We last saw Hem when he parted from Maerad at the end of

The Naming,

as they fled Norloch; and now we pick up the story on his arrival with the Bard Saliman in the populous and ancient city of Turbansk. Here we see a society very different from Annar in many ways – despite the commonalities of Bardic authority – through the naive eyes of a bewildered young boy and against the darkening background of gathering war. The battle against the depredations of the Nameless One intensifies as the immortal despot of Den Raven (known more commonly in the south by his usename, Sharma) threatens to destroy all the cultures of the Light in Edil-Amarandh.

As in the previous volumes, for the purposes of this text I have treated Annaren as the equivalent of English and left untranslated some terms from other languages, in this case, most commonly, Suderain – the language spoken across both the Suderain and the Amdridh peninsula. A couple of Annaren experts have questioned this decision, arguing that in doing this I give a false sense of the centrality of Annaren and imply that it was an imperial language like global English, which, for all its wide usage, it was not. I can only note their objections here, and answer that it seemed to me to be the best solution at the time as the original text was, indeed, written in Annaren.

As I worked on the text, it was impossible to resist reflecting on how many parallels exist between our own time and that of this ancient story. Our world has darkened considerably in the early years of the twenty-first century, suggesting to this reader at least a contemporary relevance in some of the descriptions of war in the volumes that make up

The Crow.

The

Naraudh Lar-Chane's

subtextual concerns about the relationship between human beings and the natural environment seem equally timely. This is, in part, a function of the universality of all art. But I can't help reflecting sadly that it says little for the human race that we are no closer to resolving these questions than we were in the days when Bards and the Balance held sway.

I have now spent so long on this task of translation that it is almost impossible to imagine my life without it; and it is fair to say that I did not realize, when I began to translate

The Naming,

how much it would take over my life. The work is still a long way from completion: there are still the final, and most difficult, two volumes before me. This is not a complaint: the many hours spent debating intricacies of Annaren syntax or the finer points of Bardic ethics, the days in libraries poring over ancient scripts or microfiche, attempting to decipher some arcane detail of life in the vanished realm of Edil-Amarandh, have been among the most rewarding in my life. And this work has made me many friends, both readers and those who have helped me in my research, who have enriched my life immeasurably.

As always, a work of this kind is created with the help of many people, most of whom I do not have the space to acknowledge here. Firstly, as always, I want to thank my family for their good-humored tolerance of this obsessive work – my husband, Daniel Keene, for his support of this project and his proofing skills, and my children, Joshua, Zoe, and Ben. I am again grateful to Richard, Jan, Nicholas, and Veryan Croggon for their generous feedback on early drafts of the translation. Chris Kloet, my editor, has my endless gratitude for her unfailing support and sharp eye, which has saved me from many a grievous error. Among my many colleagues who have kindly helped me with suggestions and advice, I particularly wish to thank: Professor Patrick Insole of the Department of Ancient Languages at the University of Leeds for again permitting me to quote generously from his monograph on the Treesong in the Appendices; Dr. Randolph Healy of Bray College, Co. Wicklow, for his advice on the mathematics of the Suderain Bards; and Professor David Lloyd of the University of Southern California, for his acute and valuable analyses of the complexities of political power in Edil-Amarandh during many pleasurable conversations. Lastly, I would like also to acknowledge the courtesy and helpfulness of the staff of the Libridha Museum at the University of Queretaro during the months I spent there researching the

Naraudh Lar-Chane.

Alison Croggon Melbourne, Australia

A Note On Pronunciation

Most Annaren proper nouns derive from the Speech, and generally share its pronunciation. In words of three or more syllables, the stress is usually laid on the second syllable: in words of two syllables, (e.g.,

lembel, invisible)

stress is always on the first. There are some exceptions in proper names; the names

Pellinor

and

Annar,

for example, are pronounced with the stress on the first syllable.

Spellings are mainly phonetic.

a

– as

in flat. Ar

rhymes with

bar.

ae

– a long

i

sound, as in

ice. Maerad

is pronounced

MY-rad.

ae

– two syllables pronounced separately, to sound

eye-ee. Maninae

is

pronounced

man-IN-eye-ee.

ai

– rhymes with

hay. Innail

rhymes with

nail.

au –

ow. Raur

rhymes with

sour.

e

– as

in get.

Always pronounced at the end of a word: for example,

remane, to walk,

has three syllables. Sometimes this is indicated with

e,

which indicates also that the stress of the word lies on the

e

(for example,

He, we,

is sometimes pronounced almost to lose the

i

sound).

ea

– the two vowel sounds are pronounced separately, to make the sound

ay-uh. Inasfrea, to walk,

thus sounds:

in-ASS-fray-uh.

eu –

oi

sound, as in

boy.

i

– as in

hit.