The Crusades: The Authoritative History of the War for the Holy Land (53 page)

Read The Crusades: The Authoritative History of the War for the Holy Land Online

Authors: Thomas Asbridge

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History, #bought-and-paid-for, #Religion

On 31 July 1191 Philip sailed north to Tyre with Conrad, taking with him half of Acre’s captive garrison, and a few days later the French king left the Holy Land and the Third Crusade. Oath or not, Richard remained deeply suspicious of Philip’s intentions, immediately dispatching a group of his most trusted followers to shadow the king on his return journey and deliver warning of his homecoming to England and beyond. A letter composed by Richard on 6 August to one of his leading English officials offers a glimpse of his state of mind at this point, his desire to capitalise upon Philip’s withdrawal playing alongside new fears:

Within fifteen days [of Acre’s fall] the king of France left us to return to his own land. We, however, place the love of God and His honour above our own and above the acquisition of many regions. We shall restore the [Latin kingdom] to its original condition as quickly as possible, and only then shall we return to our lands. But you may know for certain that we shall set sail next Lent.

Up to this point, Richard had been able to focus upon the prosecution of the Third Crusade. With Philip by his side he had enjoyed a degree of confidence about the security of his western realm. From now on, his concerns would mount–each day spent in the East was time gifted to his rival. Never again could the Lionheart afford to be so single-minded in the pursuit of the Holy Land’s recovery.

62

IN COLD BLOOD

Richard’s first concern, now that he possessed sole command of the crusade, was to see the terms of Acre’s surrender fulfilled so that the reconquest of the Latin East might continue. With time now a burning issue, the maintenance of momentum became crucial. Barely two months of the normal fighting season remained, so a near-immediate march south would be necessary to achieve overall victory before the onset of winter. Richard needed a few weeks to rebuild Acre’s fortifications to ensure that the city would be defensible in his absence, but at the same time he began pressuring Saladin for a precise timetable for the implementation of the peace settlement’s terms.

Both sides now entered into a delicate, but potentially deadly, diplomatic dance. The sultan knew that, for Richard, speed was of the essence. But so long as the king still had thousands of prisoners and an immensely profitable treaty to cash in, he would effectively be immobilised. If negotiations could be strung out, the crusaders might even find themselves mired at Acre throughout that autumn and winter. The Lionheart, too, was clearly aware that his opponent would seek to employ just such delaying tactics. Both he and Saladin recognised that a game was being played; what they could not yet gauge was their adversary’s temperament. Would the rules be adhered to, indeed, were their respective rules the same? And what risks and sacrifices would the other be prepared to countenance?

For both parties, the dangers inherent in a miscalculation were grave. Richard stood to lose a considerable fortune in ransom, and to forgo the repatriation of more than 1,000 Latin captives and Outremer’s most revered relic. But more significantly, if he permitted postponement and procrastination to creep into proceedings, he risked the collapse of the entire crusade. For without forward progress, the expedition would surely founder under the weight of disunity, indolence and inertia. The equation confronting Saladin was perhaps simpler: the lives of some 3,000 captive Muslims balanced against the need to stifle the crusade.

The pact agreed on 12 July originally stipulated a timescale of thirty days for the fulfilment of terms. While Saladin showed a willingness to accommodate Frankish demands–allowing one group of Latin envoys to visit Damascus to inspect Christian prisoners and another to view the relic of the True Cross–he seemed equally determined to buy himself more time. Richard, inundated by delegations of silky-tongued, gift-laden Muslim negotiators, appeared to relent on 2 August. Even though his forces were nearly ready to move out of Acre, the Lionheart agreed to a compromise: the terms of the surrender would now be met in two to three instalments, the first of which would see the return of 1,600 Latin prisoners and the True Cross and the payment of half the money promised, 100,000 dinars. Saladin may well have read this as an indication that the English king could be manipulated, but if so he was badly mistaken. In fact, Richard had his own reasons for acceding to a short delay in proceedings–with Conrad of Montferrat stubbornly refusing to return Philip Augustus’ share of the Muslim captives, now ensconced at Tyre, the Lionheart was, for the moment, in no position to meet his end of the bargain.

By mid-August, however, this difficulty had been redressed, the marquis forced into line by Hugh of Burgundy and the captives returned. With everything in place Richard was now eager to proceed. From this point forward, the contemporary evidence for this episode becomes increasingly muddled, with both Latin and Muslim eyewitnesses peppering their accounts with mutual recrimination, clouding the exact details of events. It does appear, however, that Saladin misjudged his opponent. Modern commentators have often suggested that the sultan was having difficulty amassing the money and prisoners required, but this is not supported by contemporary Muslim testimony. It seems more likely that, with the deadline for the first instalment–12 August–now passed, he began deliberately to equivocate. To Richard’s evident disgust, Saladin’s negotiators now sought to insert new conditions into the deal, demanding that the entire garrison should be released upon settlement of the first instalment, with hostages exchanged as guarantors that the later payment of the remaining 100,000 dinars would be made. When the king responded with blunt refusal, an impasse was reached.

Settled in his camp at Saffaram, the sultan must have imagined that there was still room for negotiation, that Richard would tolerate further delay in the hope of an eventual resolution. He was wrong. On the afternoon of 20 August, Richard marched out of Acre in force, setting up a temporary camp beyond the old crusader trenches, on the plains of Acre. Watching from their vantage point on Tell al-Ayyadiya, Saladin’s advance guard was puzzled by this sudden flurry of activity. They withdrew to Tell Kaisan, dispatching an urgent message to the sultan. Richard then showed his hand. The bulk of Acre’s Muslim garrison–some 2,700 men–were marched out of the city, bound in ropes. Herded on to the open ground beyond the Frankish tents, they huddled, rank with fear and confusion. Were they to be released after all?

Then as one man, [the Franks] charged them, and with stabbings and blows with the sword they slew them in cold blood, while the Muslim advance guard watched, not knowing what to do.

Too late to intervene, Saladin’s troops mounted a counter-attack but were soon beaten off. With the sun setting, Richard turned back to Acre, leaving the ground stained red with blood and littered with butchered corpses. His message to the sultan possessed a stark clarity. This was how the Lionheart would play the game. This was the ruthless single-mindedness that he would bring to the war for the Holy Land.

No event in Richard’s career has elicited more controversy or criticism than this calculated carnage. Describing a search of the plain made by Muslim troops on the following morning, Saladin’s adviser Baha al-Din reflected on the event:

[They] found the martyrs where they had fallen and were able to recognise some of them. Great sorrow and distress overwhelmed them for the enemy had spared only men of standing and position or someone strong and able-bodied to labour on their building works. Various reasons were given for the massacre. It was said that they had killed them in revenge for their men who had been killed or that the king of England had decided to march to Ascalon to take control of it and did not think it wise to leave that number in his rear. God knows best.

Baha al-Din noted that the Lionheart ‘dealt treacherously towards the Muslim prisoners’, having received their surrender ‘on condition that they would be guaranteed their lives come what may’, at worst facing slavery should Saladin fail to pay their ransom. The sultan met the executions with a measure of shock and rage. Certainly, in the weeks that followed, he began ordering the summary execution of any crusader unfortunate enough to be captured. But equally, by 5 September, he had sanctioned the re-establishment of diplomatic contact with the English king and some members of his entourage went on to develop close, almost cordial, relations with Richard. On balance, they and Saladin seemed to have taken the whole grim episode for what it probably was: an act of military expediency, designed to convey a brutal, blunt statement of intent. More generally, the slaughter seems to have sent a tremor of fear and horror through Near Eastern Islam. Saladin recognised that, in the future, his garrisons might choose to abandon their posts rather than face a siege and possible capture. But even for Muslim contemporaries, the events of 20 August did not prompt the universal or unmitigated vilification of the English king. He remained both ‘the accursed man’ and ‘

Melec

Ric’, or ‘King Ric’, the spectacularly accomplished warrior and general. In time, the massacre took its place alongside other crusader atrocities, like the sack of Jerusalem in 1099, as a crime that did not, in reality, spark an unquenchable firestorm of hatred, but could be readily recalled in the interests of promoting

jihad

.

63

Of course, Richard’s treatment of his prisoners also impacted upon his image within western Christendom, in some ways with a far more lasting and powerful effect. Calculated or otherwise, his actions could be presented as having contravened the terms agreed when Acre surrendered. Should Richard be seen to have broken his promise, he might be open to censure, the transgressor of popular notions regarding chivalry and honour. Fear of such criticism can be detected in the measured and carefully managed manner in which the king and his supporters sought to present the executions.

The dominant issue was justification. In Richard’s own letter to the abbot of Clairvaux, dated 1 October 1191, he stressed Saladin’s prevarication, explaining that because of this, ‘the time limit expired, and, as the pact which he had agreed with us was entirely made void, we quite properly had the Saracens that we had in our custody–about 2,600 of them–put to death’. Some Latin chroniclers likewise sought to shift blame on to the sultan–affirming that Saladin began killing his own Christian captives two days before Richard’s mass execution–and also explained that the Lionheart acted only after holding a council, and with the agreement of Hugh of Burgundy (who was now leading the French). Despite a few traces of censure in the West–the German chronicler ‘Ansbert’, for example, denounced the barbarity of Richard’s act–the English king seems to have escaped widespread condemnation.

Meanwhile, assessments by modern historians have fluctuated over time. Writing in the 1930s, when the general view of the Lionheart as a rash and intemperate monarch still held sway, René Grousset characterised the massacre as barbarous and stupid, concluding that Richard was moved to act by raw anger. More recently, John Gillingham’s forceful and hugely influential scholarship has done much to rejuvenate the king’s reputation. In Gillingham’s reconstruction of events at Acre, the Lionheart comes across as a calculating and clear-headed commander; one who recognised that the resources to feed and guard thousands of Muslim prisoners could not be spared, and thus made a reasoned decision, driven by military expediency.

64

In truth, King Richard’s motives and mindset in August 1191 cannot be recovered with certainty. A logical explanation for his actions exists, but this in itself does not eliminate the possibility that he was moved by ire and impatience.

King Richard I of England was now free to lead the Third Crusade on to victory: Acre’s walls had been rebuilt and its Muslim garrison ruthlessly dispatched; Richard had secured the support of many leading crusaders, including his nephew Henry II, count of Champagne; even Hugh of Burgundy and Conrad of Montferrat had shown at least nominal acceptance of the Lionheart’s right to command, although Conrad remained ensconced in Tyre.

65

Now the expedition’s next goal had to be determined. Little or nothing could be achieved by staying at Acre, but to leave the city by land would expose the crusade to the full ferocity of Saladin’s troops. In the Middle Ages an army was at its most vulnerable while on the move in enemy territory. Richard’s only alternative to a land advance was the sea, but he seems quickly to have rejected the idea of a strategy based purely on naval power. Large as his fleet now was, the transportation of the entire military machinery of the crusade would be a formidable challenge; even more significantly, should he fail to capture a suitable port to the south, the whole offensive would collapse. The Lionheart eventually settled on a combined approach–a fighting march that would hug the Mediterranean coastline south, closely shadowed and supported by the Latin navy. This ruled out an inland advance on Jerusalem, but in any case the obvious route to the Holy City ran south along the coast road to Jaffa and then east into the Judean hills–a path similar to that taken by the First Crusaders almost a century earlier.

However, Richard’s strategic intentions in summer 1190 are unclear. The Third Crusade had been launched to recover Jerusalem, but it is far from certain that this was the king’s first objective that August. He may well have been planning to use the port of Jaffa as a springboard for a direct advance on the Holy City. But a more oblique approach also presented itself; one that targeted the coastal city of Ascalon to the south, disrupting Saladin’s lines of communication with Egypt. Given the sultan’s reliance upon Egypt’s wealth and resources, this latter policy promised to cripple the Muslim military machine, opening the door to the eventual reconquest of Jerusalem, or, perhaps, to the seizure of the Nile Delta itself.

Of course, the lack of clarity surrounding Richard’s plans was, in part, a direct result of the king’s own deliberate evasiveness. It made perfect sense for him to conceal his strategy from Saladin, because this forced the sultan to dilute his resources by preparing for the defence of two cities rather than just one. Muslim sources certainly indicate that, to an extent, this ruse worked. By late August Saladin had heard rumours that the crusaders would march on Ascalon, but knew that once they reached Jaffa they could just as easily strike inland. Soberly informed by one of his generals that both Ascalon and Jerusalem would require garrisons of 20,000 men, the sultan eventually concluded that one of the two would have to be sacrificed.

In fact, it is quite possible that Richard had not yet settled upon a definitive goal. The bulk of his army might have had their eyes firmly fixed upon the Holy City, but he perhaps looked to retain a flexibility of approach, hoping to reach the intermediary objective of Jaffa and then decide. This might have seemed a sensible strategy at the time, but in truth the king was merely storing up problems for the future.

THE FINEST HOUR

Richard’s immediate intention was to march the armies of the Third Crusade–totalling between 10,000 and 15,000 men–down the coast of Palestine, at least as far as the port of Jaffa. But it was not territorial conquest, nor even the pursuit of battle, that dominated the Lionheart’s tactical outlook upon leaving the relative safety of Acre. Instead, survival was his guiding principle–the preservation of human manpower and military resources, to ensure that the crusading war machine reached Jaffa intact. This in itself presented enormous challenges. Richard knew that, while on the move, his army would be horribly vulnerable, subject to vicious, near-constant skirmishing attacks from enemy soldiers now baying with vengeful wrath for Frankish blood. He could also expect that Saladin would seek to lure the crusaders into open battle on ground of his choosing.

With all this in mind, it might at first glance be imagined that speed was the answer; that Richard’s best chance lay in prosecuting the eighty-one-mile march to Jaffa as quickly as possible in the hope of evading the enemy. After all, the ground could be covered in four to five days and the king was short of time. In fact, Richard resolved to advance from Acre at an incredibly measured, almost ponderous pace. Latin military logic of the day dictated that control was the key to a successful fighting march: troops needed rigidly to maintain a tightly packed formation, relying upon strength of numbers and the protection afforded by their armour to weather the storm of enemy charges and incessant missile attacks. Richard set out to take this theory to extreme limits.

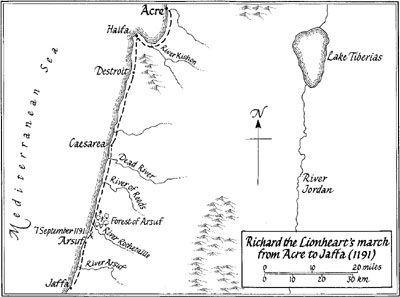

Historians have lavished praise upon the Lionheart’s generalship in this phase of the expedition, describing the advance from Acre as ‘a classic demonstration of Frankish military tactics at their best’ and commending the crusaders’ ‘admirable discipline and self-control’. In many ways, this was Richard’s finest hour as a military commander. One of his greatest moments of genius was the formulation of a strategy coordinating the land march with the southward progress of his navy. With the eastern Mediterranean now firmly in Latin control, the king sought to maximise the utility of his fleet. An army engaged in a fighting march could ill afford the burden of a large baggage train, but equally could not risk running out of food and weapons. Thus, while the land force was to carry ten days’ supply of basic rations, made up of ‘biscuits and flour, wine and meat’, the vast bulk of the crusade’s martial resources were loaded on to transport ships known as ‘snacks’. These were to rendezvous with the march at four points along the coast–Haifa, Destroit, Caesarea and Jaffa–while more lightly stocked smaller boats would sail close to the shore, keeping pace with the army to offer near-constant support. One crusader wrote: ‘So it was said that they would journey in two armies, one travelling by land, one by sea, for no one could conquer Syria any other way as long as the Turks controlled it.’ Richard’s coastline-hugging route south also promised to offer his troops protection from enemy encirclement. Wherever possible, the crusaders would advance with soldiers on the right flank practically wading in the sea, thereby eliminating any possibility of attack on that front. By these measures Richard hoped to minimise the negative impact of marching through enemy territory. This sophisticated scheme was evidently the product of advanced planning and probably relied in part upon the Military Orders’ local knowledge. Success would depend upon the maintenance of martial discipline and in this regard Richard’s force of personality and unshakeable valour would be critical.

In spite of all of this, neither the Lionheart’s achievements nor the mechanistic precision of this march should be exaggerated. Even in this phase of the crusade Richard faced difficulties, a fact generally ignored by modern commentators. Indeed, his first problem–the actual commencement of the march–was nothing less than an embarrassment. One might expect that, as the expedition’s only remaining monarch, Richard’s authority would have been unquestioned; after all, he had even taken the trouble of paying potentially intractable French crusaders, like Hugh of Burgundy, to ensure their loyalty. Nevertheless, the English king had an inordinate amount of trouble actually convincing his fellow Franks to leave Acre.

The problem was that the port had become a comfortable, even enticing, refuge from the horrors of the holy war. Packed ‘so full of people that it could hardly hold them all’, the city had transformed into a fleshpot, offering up all manner of illicit pleasures. One crusader conceded that it ‘was delightful, with good wines and girls, some very beautiful’, with whom many Latin crusaders were ‘taking their foolish pleasure’. Under these conditions Richard had to work hard to educe obedience. On the day after his massacre of the Muslim captives, he established a staging post on the plains south-east of the port, just beyond the old crusader trenches. His most loyal followers accompanied him, but others were reluctant. One supporter admitted that the Lionheart had to resort to a mixture of flattery, prayer, bribery and force to amass a viable force, and even then many were still left in Acre. Indeed, throughout the first stage of the fighting march stragglers continued to join the main army. To begin with at least, the restrained pace of Richard’s advance–now so admired by military historians–seems primarily to have been adopted to allow these recruits to catch up.

66

The march begins

The main army struck out south on Thursday 22 August 1191. To stamp out any residual ‘wantonness’ among his troops, Richard ordered that all women were to be left behind at Acre, although an exception was made for elderly female pilgrims who, it was said, ‘washed the clothes and heads [of the soldiers] and were as good as monkeys at getting rid of fleas’. For the first two days, Richard rode in the rearguard of his forces, ensuring the maintenance of order, but despite expectations only negligible resistance was met. Saladin, unsure of the Lionheart’s intentions and perhaps fearing a frontal attack on his camp at Saffaram, deployed only a token probing force at this stage. Having covered barely ten miles in two days, the crusaders crossed the Belus River and made camp, resting for the whole of 24 August, ‘wait[ing] for those of God’s people whom it was difficult to draw out of Acre’.

67

Richard the Lionheart’s March from Acre to Jaffa (1191)

At dawn the next day Richard set out to cover the remaining distance to Haifa. The army was split into three divisions–the king taking the vanguard, a central body of English and Norman crusaders, and Hugh of Burgundy and the French bringing up the rear. For now, coordination between these groups was limited, but they were at least united by the sight of Richard’s royal standard aloft in the centre of the host. As the crusade inched south, so too did the king’s dragon banner at the army’s heart, affixed to a huge iron-clad flagpole, drawn on a wheeled wooden platform and protected by an elite guard. Visible to all, including the enemy (who likened it to ‘a huge beacon’), so long as it flew this totem signalled the Franks’ continued survival, helping men to hold their fear in check in the face of Muslim onslaught. That Sunday, such resolve would be sorely needed.

To reach Haifa, Richard had led the crusade on to the sandy beach running south from Acre. Unbeknownst to the Latins, Saladin had broken camp that morning (25 August), dispatching his baggage train to safety and ordering his brother al-Adil to test the strength and cohesion of the Christians’ fighting march. A confrontation was coming. As the day wore on an atmosphere of palpable unease settled on the slowly advancing crusader army. On their left, among the rolling dunes, Muslim troops appeared, shadowing their march, watching and waiting. Then a fog descended and panic began to spread. In the confusion, the French rearguard, containing the light supply train of wagons and carts, slowed down, breaking contact with the rest of the army, and at that moment al-Adil struck. One crusader described the sudden Muslim attack that followed:

The Saracens rushed down, singling out the carters, killed men and horses, took a lot of baggage and defeated and put to rout those who led [the convoy], chasing them into the foaming sea. There they fought so much that they cut off the hand of a man-at-arms, called Evrart [one of Bishop Hubert Walter’s men]; he paid no attention to this and made no fuss…but taking his sword in his left hand, stood firm.

With the rearguard ‘brought to a standstill’, and disaster impending, news of the attack raced up the line to Richard. Recognising that direct and immediate intervention would be necessary if a deadly encirclement of the French was to be avoided, the Lionheart rode back at speed. A Christian eyewitness described how ‘galloping against the Turks [the king] went into their midst, quicker than a flash of lightning’, beating off the Muslim skirmishers through sheer force of arms, reconnecting the rearguard with the main body of the army. With the enemy melting back into the dunes, the Latin army was left shaken but intact. Having survived this first challenge, the crusaders reached Haifa either that night or early the next morning, camping there throughout 26 and 27 August.

68

It was clear that the crusaders would have to regroup. Modern scholarship has emphasised the skill with which Richard organised and upheld the Frankish marching formation upon leaving Acre. But this ignores the fact that, to a significant degree, the Lionheart and his men actually had to learn by their mistakes. One crusader wrote that, after the experiences of 25 August, the Franks ‘made great efforts and conducted themselves more wisely’. While continuing to wait for the army to muster fully–for troops were still arriving from Acre, now mostly by ship–the king set about reordering his forces. Equipment was pared down; the poor especially had begun the march overburdened ‘with food and arms’, so that ‘a number of them had to be left behind to die of heat and thirst’. At the same time, a far more structured marching order was established and this seems to have been followed for the remainder of the journey south.