The Crystal City Under the Sea (22 page)

“Your daughter I am,” said Hélène, taking her in her arms, “and I could not be more your daughter, if a hundred Renés were to marry me. But give up, dear auntie, a project which would bring no happiness to any one. Let us face things as they are: René does not want me, and—excuse my plainness — I do not want him! Besides, we have both of us wishes in other directions,—I mean René has made his choice, and it is irrevocable. Will you, for the sake of a chimerical idea, make him unhappy?”

“Make him unhappy? God forbid! All I wish for is to see him happy.”

“Then give him the consent he so eagerly longs for, or, better still, before he asks it, tell him that you take Atlantis to your heart as your daughter?”

“Atlantis, my daughter-in-law? a Nereid, a sea-nymph, a siren, a woman dressed like Polymnia?” said Madame Caoudal, trembling.

“I can lend her one of my dresses,” said Hélène, tranquilly.

“What would our friends say, what would the neighbours think?”

“That a more beautiful, noble, interesting girl never came into the Caoudals’ house, that you have found here a daughter-in-law worthy of you. What is there, in short, to prevent you? Atlantis is a stranger, it is true. Yet I do not like the word strange for her, — it does not suit her pure and peaceful face. That she is noble in heart and training, you are as fully convinced as I. And don’t you think, dear aunt, that if her father has accepted Rend as a son, he must have made an effort to overcome a disinclination quite as strong as anything you can feel, to meet their wishes; and I am convinced that he has done so. Do not let him surpass you in generosity, Aunt Alice; go to them, they deserve it; and René would be so pleased!”

Hélène followed up her advocacy, and her face lighted up with generous animation, all unaware that Patrice had just appeared on the scene, and had stopped, with a look of admiration on his face.

“Well, Stephen, what news?” said Madame Caoudal, who was the first to see him.

“Nothing decisive so far; but I am not without hope,— relatively, be it understood,—for, at his age, it would be impossible to expect him to keep alive much longer. I have already applied electricity to him with good effect. For the present our fair hostess insists upon my coming to refresh and rest myself with you. To tell the truth,” said he, as the two ladies busied themselves finding a seat for him and placing food before him, “ I do not really need either rest or food. I never felt in better condition. What an enchanted place this is, what a delightful place to visit!”

“Has the invalid recovered consciousness?” inquired Madame Caoudal.

“Not yet, but it cannot be long before he does.”

“Do you think it would be an intrusion if I went to his room? I should like him to find me there when he does, so that I may apologize for our having come, and to pay our respects to him,” said the good lady, in a ceremonious manner; “and also,” she added, sweetly, “1 should like to help this young girl in the sad trial that is awaiting her, though we have, alas! nothing but sympathy to offer her.”

“Be sure that she will appreciate it,” cried Patrice, with warmth, “ and she could not be in better hands. I have often seen death-beds, but never anything like this one. Think of it! That narrow couch where the old man is dying contains the whole universe for this young girl,—her sole companion, till now. Her behaviour is admirable; such simple dignity and self-control in her grief; and yet how heartrending the separation that is in store for her!” “Let us go to her,” said Madame Caoudal, promptly, “ since you authorize it; I should reproach myself if I delayed.”

They all rose and left the salon, the doctor leading the way to the sick chamber. Atlantis and René had resumed their place at the bedside. The old man, stretched on the purple couch, still lay as immovable as a statue, but there was nothing painful in his appearance. Some minutes previous, a faint warm tinge had given a little animation to his features. He looked so noble thus, that his two visitors were arrested by a feeling of reverence, as if they were on the threshold of a sanctuary. Atlantis and René came forward and begged them to be seated; but Patrice, accustomed by his calling to read people’s hearts, and always ingenious in doing a kindness, felt sure that the mother and son were longing for a confidential chat; and, oh the other hand, no one could possibly soothe and sustain the heart of Atlantis with more delicacy than Hélène.

“With your permission,” he said, without further preamble, “I should like for an hour or two to be left alone with my patient. Here is a little salon,” pointing to an adjoining room, “ where you can find your mother a comfortable seat, my dear Caoudal, and be close at hand to help me if I want you. As for you, young ladies, I take the liberty, as a doctor, of ordering you to take a walk. I have no need of you just now; but your help, later on, may be necessary. It is, therefore, your duty to husband your strength, and a little change will distract your thoughts. I am sure Mademoiselle Atlantis would like to show her visitor these beautiful gardens.”

“Will you?” said Hélène, with a smile that was irresistible.

“Oh, yes! I should like it,” said Atlantis, raising her sweet eyes to her new friend’s face.

The two girls withdrew. They walked along for some time in silence, each occupied with her own thoughts. Presently Atlantis spoke.

“Hélène,” said she, “ I want to ask you one thing, but I hardly know how to express myself. How is it that René, having known you, came to choose me?”

“I am René’s sister,” said Hélène, simply, “ and consequently yours.”

“My sister! you will be my sister! Oh! it is too much happiness in one day!”

“Dear Atlantis,” said Hélène, throwing her arm round her, “ do you not see that it is I who am the favoured one?”

The conversation went on in this strain. Many confidences were exchanged, and when, in two hours’ time, René came to summon them to the sick-room, they were friends for life. Patrice wished them to be present, as Charicles showed signs of awaking. Assembled round the bed, they all waited in silence for the change which many signs warned them of.

All of a sudden, the most unexpected thing happened. The bell at the water-gate made itself heard, and twice the sound was repeated. Who could be ringing and wanting an entrance at such a depth beneath the water?

CHAPTER XIX

THE SECOND RING AT THE BELL.

M

UST I open the door, sir?” said Kermadec, at length. “Open the door? You speak as if it were nothing. Who in the name of all that’s wonderful could want to see us at this time? Such people ought to be left to wait till the Day of Judgment, — people who could knock at the door of a dying man’s house like this.” A third peal, pressing, energetic, cut short his words.

“The determined rascals seem impatient,” observed Patrice, smiling, “What will our charming hostess say to it? Must we allow these additional intruders to invade her dwelling?”

“Our solitude has come to an end forever,” replied Atlantis, with dignified sweetness. “Charicles, I am sure, would permit these newcomers to enter his house. In his place I take it upon me to do so. Go, Kermadec, and greet the frightened travellers for him; offer them water for washing, bread and salt, and bring them to us when they have removed the dust of their journey hither.”

“Dust! what a way to speak!” thought Kermadec. but turning to obey, however. “They are more likely to be covered with shells and sea-wrack; but we will see.” He went off, swinging along with his sailor’s waddle; and a few minutes elapsed. Then exclamations of surprise were heard, and suddenly Kermadec threw open the great door, and, slipping on one side, with a broad grin on his face, he announced in a loud voice:

“His highness, the Prince of Monte Cristo, and Captain Sacripanti desire to pay their respects to the ladies and gentlemen.”

René and Patrice looked much annoyed, and a frown darkened Madame Caoudal’s face, as she drew her shawl round her shoulders, by way of placing a barrier between herself and these tiresome people. Hélène could not help smiling”. As for the daughter of Charicles, she placidly awaited the entrance of the visitors. They did n’t keep her long waiting. The prince, on the best of terms with himself, as usual, his nose in the air, his eyes red and prominent, and his hat under his arm, came forward with the step of a conquering hero, and saluted the ladies. Behind him, Sacripanti, more redolent of hair-oil than ever,—with watch-chain, rings, and scarf-pin more in evidence than ever,—described a series of bows, which were meant to be obsequious, but were only grotesque.

“Captain Sacripanti was anxious to come with me in the character of interpreter,” explained the prince, with a majestic wave of the hand. “All ancient and modern languages are equally familiar to him, and I thought that he would be of considerable service to me, in communicating my ideas to the interesting family who have fixed upon this place of residence. And a propos, my dear Caoudal, indulge, I beg of you, the wish which devours me to be introduced to this noble old man and his adorable daughter, for I presume that mademoiselle is his daughter?”

“Indeed,” said René, in anything but the best of tempers, “I must beg you to notice that our host, Charicles, is not in a condition just at present to be introduced to any one. Explain; first of all, where you have come from, and how it is we see you in these parts. I cannot understand it at all!”

“These parts seem to be getting a little common and ordinary,” said Kermadec, unceremoniously, used to express himself freely.

“Eh? what?—common?” said the prince, seating himself at his ease in an ivory chair, which creaked and groaned under his weight. “ Know, my fine fellow, that any place the Prince of Monte Cristo might find himself could hardly be described as common! But, in replying to your question, my good Caoudal, I will, as the Irish do, ask you another: Have I not already seen mademoiselle? Have not my poor eyes already had a glimpse of this miracle of grace and beauty on the occasion of our memorable descent in the diving-bell, from the Cinderella?”

“No doubt,” answered René, impatiently.

“Well, there is no need for me to explain myself further. Any one who knows Monte Cristo, knows that, having once seen this marvellous beauty, it goes without saying that he must see her again.” And he looked round upon them all with the liveliest satisfaction.

“You see you are supplanted, my dear Hélène,” said Madame Caoudal, in a low tone, “but I don’t think you will break your heart.”

“Still that does not explain your presence among us,” replied René, coldly.

“Ah, ha! my dear Caoudal, with your usual clear-headedness, you have hit the nail on the head. The diving-bell being, as no one knows better than yourself, inadequate for the purpose, I thought of making another, in which to descend alone, since you unexpectedly left me. And then, of course, I thought that the simplest thing to do was to learn your movements, and follow your example. My respected friend, Captain Sacripanti, for a certain pecuniary consideration, undertook to assist me in the matter.” “In other words, acted as a spy upon me,” said René, shortly.

“Oh! spy is too strong a word, my friend. You have not hidden yourself, that I am aware of. Sacripanti, having learnt that you were having a submarine boat made, and that the public were admitted to see it, I had no difficulty in guessing what you proposed to do, and, as my princely coffers are not yet empty, I simply ordered another boat like yours to be made at the same makers, and mine was completed a few days after the Titania. I embarked with my dear friend, and here I am. I hardly expected,” added the prince, gallantly, “to find so numerous and charming a company in this submarine kingdom,”

“Any more, certainly, than one would have expected to see you,” said René, brusquely. “But, Patrice, unless I am mistaken, our venerable host appears to be giving some signs of life. Would it not be well to renew our efforts to help him?”

“For which purpose, I need hardly say, I am entirely at your service,” said Monte Cristo, coming forward in a dignified manner. “The laws of hospitality are sacred; I shall not think it derogatory to lavish every attention on this venerable old man, who, by the way,—if I may judge by appearances,—is extremely well born,”

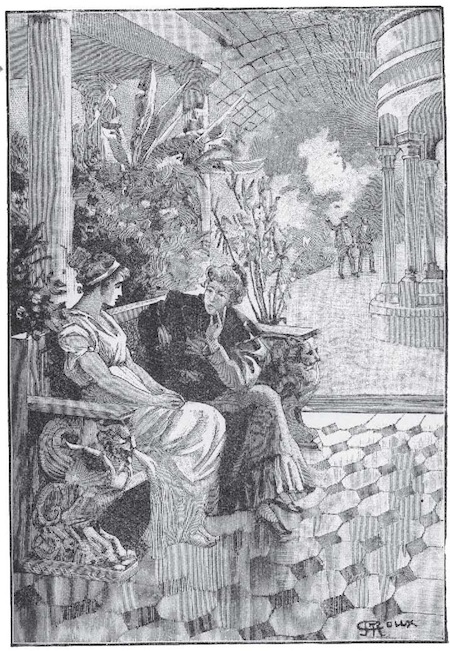

René turned from him, out of all patience, and the doctor and he, assisted by Kermadec, betook themselves to the application of electricity interrupted by the advent of the prince. While they were engrossed with their efforts at the bedside, Monte Cristo and Aunt Alice, forgetting the skirmishes which were the chief feature of their intercourse a short while before, became, for the moment, the best friends in the world. Hélène and Atlantis chatted apart, much amused at the mistakes made by the Greek girl, in her endeavours to speak French, of which René had taught her a few phrases at brief intervals, during their long talks at her father’s bedside. Sacripanti, alone, was unoccupied; but, without appearing to trouble himself at the ease with which the others grouped themselves, he came and went up and down the vast hall, ferreting and rummaging in corners, apparently finding very much to his taste all that he discovered.

At length, after a further application of electricity, Charicles sighed deeply, opened his eyes, moved his arms, and made an effort to rise. René passed his arm under his shoulders, and the old man looked round deliberately upon them all. He seemed much astonished at the sight of so many faces. “Where am I?” he murmured. “Can I be already in the land of shadows? Who are these strangers round my couch, or do I still dream?”

“I am here, my dear host,” said René, pressing his hand, affectionately.

“Atlantis!” added he, raising his voice.

Atlantis ran as lightly and noiselessly as a shadow, and, putting her arms round him, kissed him with tears of joy. The old man drew her feebly to his heart.

“Dear, dear child,” he said, “once more I see thee again. But tell me, — who are these strangers? Where do they come from? Are they