The Curse of the Labrador Duck (38 page)

Read The Curse of the Labrador Duck Online

Authors: Glen Chilton

And then, on a Monday afternoon in August, fully nine years, one month, and six days after my search began, “the call” came through. It was from Errol Fuller. He wanted to know if I could fly to London immediately. Captain Hewitt’s duck was back in Great Britain, but the window of opportunity to see it was extremely narrow. Lisa leapt into action, and secured me a seat on a flight arriving at Gatwick at 10:50 the next morning.

Errol and his son, Frankie, were waiting for me at Gatwick. As we drove off, Errol brought me up to date. The duck had been taken

from England to Qatar in a fashion that, if not strictly illegal, was certainly not done by the books. The Sheikh, in an apparently random whim, had decided that his Labrador Duck was to be shipped back to England so that the proper paperwork could be completed for its removal to Qatar. Since the duck had been residing in Qatar for two years, and no one had any way of forcing its extradition to England, this seemed a rather odd move. Furthermore, there was a degree of urgency to complete the paperwork, as the duck was going to be one of the star attractions in an exhibition in Qatar ten weeks hence. Indeed, the paperwork might come in the form of a temporary export license to facilitate the duck’s appearance in the exhibition, although the chances of the duck’s returning to England afterwards seemed extremely remote. Regardless, the duck was residing at an art gallery near Piccadilly and had to be taken to a firm of international art shippers in Vauxhall, where it would be held until all of the necessary paperwork would be completed, at which time it would be shipped back to Qatar. Errol was well known to the gallery owners who had taken him up on his offer to transport the duck to the shippers. The interval between the art gallery and the shipper was to be my opportunity to examine the duck. The plan was to take the duck to Errol’s home so that I could examine it at leisure. We would give it to the shippers when Errol took me back to the airport.

At the art gallery, on a street lined by an assortment of posh art galleries, we were buzzed in. Errol thought it prudent not to mention my specific interest in the duck, and so I was introduced as his colleague. I was expecting the duck to be brought to us in a stout and professionally constructed shipping container, with lots of wood and big brass screws. I was surprised when we were brought a reused cardboard box sealed with masking tape and secured with a bit of string. It sported two small red “fragile” stickers, and the words LABRADOR DUCK were scribbled on the side in felt pen. Frankly, my Christmas ornaments reside in a more secure box.

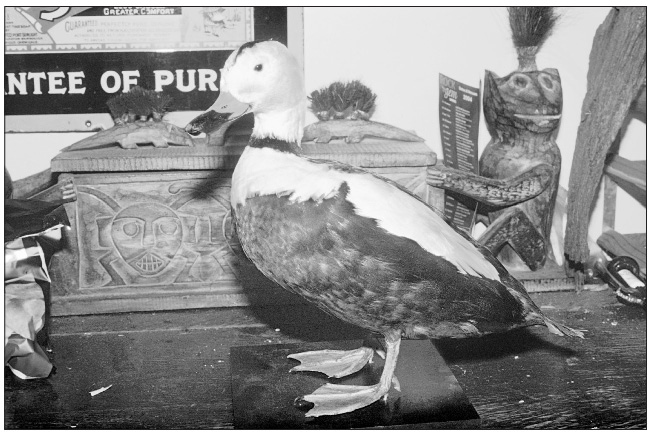

A “cursed” duck, and the final specimen in my quest to see every Labrador Duck in the world. Having changed hands many times, it is now in the collection of Sheikh Saud of Qatar.

When we got to Errol’s home, he cleared a bit of space at his kitchen table, and I set the box down. For some reason, I wasn’t in a terrible hurry to get on with my examination. Perhaps it was because we were suffering through a very hot and humid day, and I needed a breather. More likely it was because the box contained an object that I had been searching for for almost a decade, and it was to be the last new Labrador Duck I would ever see. This was it. Once I opened the box and poked at it a bit, the adventure would be over.

Frankie watched me as I cut the string, pulled off the masking tape, and reflected the box’s flaps. At first all I could see was crumpled tissue paper, but as that came away, the duck revealed itself, and my breath rushed into my chest with a whoosh.

I had seen a scanned image of a photocopy of a fifty-year-old, black-and-white photograph of the duck being examined by Richard Ford before selling it to Captain Hewitt, and from what detail remained after so much time and copying, it seemed a truly lovely specimen. Errol had warned me that the duck had been restuffed about 18 months earlier. This had been a really dangerous move; in taking

apart a specimen this old, even the most skilled taxidermist might have been left with nothing more than a pile of feathers. However, Errol had assured me that a good job had been done. My first impression was of a very artistic interpretation. When it was first found, the duck had seemed a little too alert, but the new taxidermist had given it a more relaxed look. The neck was more bent, bringing the head closer to the shoulders, and the eyes were ever so slightly closed, as though the drake was getting ready to nod off. Originally, the duck had been mounted on a base covered in pebbles and seaweed, suggesting, I suppose, the seaside where the duck had lived. This had been replaced by a simple wooden slat, 18 by 19 by 2 cm, painted black, which allowed viewers their own interpretation of the duck’s circumstances.

So far so good. Regrettably, the fellow who restuffed the duck had taken it upon himself to paint the legs, toes, and webs a uniform gray-blue. Even worse, he had painted the bill. The distal half was black, and the proximal half was mustardy yellow, overlain along the midline by a broad triangle of gray-blue. To give the taxidermist credit, he was thorough, having painted even the underside of the bill in the same mustard-yellow and battleship gray.

So I made my measurements, and drew little pictures in my notebook, and used a magnifying lens to examine wear to the tail and wing feathers. And as I poked and peered, the sun broke through the persistent British clouds, and a shaft muscled its way through Errol’s kitchen window, and fell on the duck. Something strange happened. In the afternoon sun, a few patches of particularly black feathers glowed an iridescent green. I was ready to blame my dirty contact lenses, but when I called Errol over, he said that he could see the green sheen too. Some birds have patches of iridescent green feathers, including some ducks. Was this a feature of Labrador Ducks that I had somehow missed? If the sun hadn’t come out, I wouldn’t have spotted it this time. Could all of the authors who described Labrador Ducks in life so long ago have missed this iridescence? There was certainly no green hue in Audubon’s painting. I looked, and turned my head, and blinked, and looked again, and convinced myself that the green iridescence was the result of a little subterfuge. I believe when the taxidermist was restuffing the duck, he found himself short of

feathered skin in spots, and used bits from another duck, possibly a Mallard, to fill in the gaps.

And there we have it. Some sixty years ago, this Labrador Duck was owned by someone in a country house in Kent, then by naturalist Richard Ford, by Captain Vivian Hewitt, by Hewitt’s son, Jack Parry, by bookseller David Wilson, and by my chum Errol Fuller, after which it came into the possession of an art dealer, who sold it to Sheikh Saud of Qatar. And I suppose that is the end of my story. Barring some unforeseen discovery, I can claim to have seen absolutely every stuffed Labrador Duck in the world, and no one else could make that claim, and I am sure that no one ever will. This left only a quick trip to the shippers to exchange the duck for a receipt numbered 4513/04.

Of the owners of this duck, a pretty good chunk are known to be or suspected of being dead, or well on their way. Many other protagonists in the story are dead. To be fair, an historian friend of mine pointed out that the same can be said of any very old artifact, but part of me thinks that this particular duck is not particularly charmed. Could it be cursed? Let’s wish Sheikh Saud a very long and happy life.

I

TOLD YOU

earlier that I wouldn’t reveal the end of the story of

The Maltese Falcon

. Upon further reflection, this seems to be a tease. After all, your local video store is bound to have hundreds of copies of

Spider-Man

and

Harry Potter,

but the odds are about three to one that the clerk has never heard of

The Maltese Falcon

, and would probably confuse Humphrey Bogart with Harrison Ford.

At the end of

The Maltese Falcon

, the statuette that the crew have been following turns out to be a fake, and Caspar Gutman leaves to continue his search for the real one. In the movie, Sam Spade calls the police to put them on to Gutman as a murderer, but Gutman escapes police custody, and, presumably, continues his quest. They do capture the young lady and charge her with murder. The end of the book is a little more gruesome than the movie. Gutman dies in a shoot-out with police, and so never gets the falcon statuette that he has been following for seventeen years. I searched for this single specimen of the Labrador Duck for more than nine years. Unlike Caspar Gutman, I eventually found it, and didn’t die in the chase.

A

nd that was that. I had been around and around the world with strange and wonderful traveling companions. I had examined fifty-five stuffed Labrador Ducks in thirty cities, and sampled nine eggs that later proved to have nothing to do with the birds I was after. From standing on Audubon’s hillside in Labrador to measuring my last duck, my adventures had taken me four years, nine months, and eighteen days. I had, as far as I could tell, seen every surviving stuffed Labrador Duck in the world. The end of the quest left me with a sense of elation at having completed a task that no one had ever attempted before, and that no one would ever bother to repeat. After all, twelve people have stood on the Moon, but I was the only person to have seen every Labrador Duck. But I also felt a sense of deflation that the journey was over.

To be completely forthcoming, there were several Labrador Duck specimens that I couldn’t account for, and, as friends have pointed out again and again, it is possible that new specimens remain to be discovered. How confident am I that I found them all? So confident that I will pay a reward of $10,000 to the first person who can direct me to a genuine stuffed Labrador Duck that I have not seen and described in this book.

*

I don’t want to buy the duck; I just want to examine

it. After I have verified its legitimacy, you get the money. There is no point in trying to fake me out with a duck re-created from bits of other birds; I’ve seen it all before.

If you choose to embark on your own Labrador Duck quest, you might want to start with the specimens that may have been destroyed by wartime bombing in Liverpool, Amiens, and Mainz. Perhaps you know the reprobate that stole the duck from the American Museum of Natural History in New York; perhaps you

are

the reprobate. Altenburg probably never had a Labrador Duck, but it could be worth a peek if you are in the area.

These are all long shots, but there are other possibilities. In April of 1962, Paul Hahn of the Royal Ontario Museum received a response to his questionnaire about stuffed extinct birds from Everett F. Greaton, a consultant for the Recreation Department of the Department of Economic Development at the State House in Augusta, Maine. Greaton indicated that the bird section of the museum at the State House had a stuffed Labrador Duck. Hahn didn’t include that specimen in his catalogue, and forty years later, Kris Weeks Oliveri, Volunteer Coordinator at the Maine State House Museum, assured me that there is no sign of a Labrador Duck in their collection. Maybe it is sitting on a shelf in the Governor’s office.

I’ll give you one more lead, and then you are on your own. In November of 1844, Colonel Nicolas Pike shot a drake Labrador Duck at the mouth of the Ipswich River at the south end of Plum Island, New York. History doesn’t say whether or not the duck was doing anything to provoke the colonel. Perhaps Pike just really, really hated ducks. The bird was stuffed by John Akhurst, given to the Long Island Historical Society (now the Brooklyn Historical Society), and eventually deposited in the Brooklyn Museum. The Brooklyn Museum narrowed its focus in the 1930s and 1940s, and dispensed with its natural history collection.

At my request, Deborah Wythe of the Brooklyn Museum did some digging. Between them, Charles Schroth and Charles O’Brien at the American Museum of Natural History received from the Brooklyn Museum fifty-eight cartons of bird study skins in August, 1935. If birds are packaged like cigarettes, twenty-five to a pack and eight packs to a carton, we are talking about roughly 1,600 specimens.

No mention was made of mounted specimens in general, nor about the Brooklyn Labrador Duck in particular. I have already examined every Labrador Duck specimen at the AMNH and it isn’t there. At Wythe’s suggestion, I tried the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, which apparently got many natural history specimens without much ceremony or documentation. Nancy Paine, who has the delightful job of Chief Curator at the Children’s Museum, informed me that I had hit another dead end. John Hubbard told me that the Bailey-Laidlaw Collection at Virginia Tech in Blacksburgh had received a chunk of the Brooklyn Museum’s collection, but Curt Adkisson, current curator, was able to tell me they do not have, and never did have, a Labrador Duck. It must be out there somewhere.

Good luck in your quest.

I

owe a great debt to many curators who agreed to give me access to their Labrador Ducks, which count among their most valued treasures, or who dug through their records to assure me that they didn’t have a Labrador Duck after all. That group includes Mark Adams, David Agro, Delise Alison, Miloš Anděra, Ernst Bauernfeind, Ingrid Birker, Joe Bopp, Katrina Cook, Steve Cross, James Dean, René Dekker, Felicity Devlin, Siegfried Eck, Scott Edwards, Clemency Fisher, Michaela Forthuber, Anita Gamauf, Michel Gosselin, David Green, Andy Grilz, Ed Hack, Shana Hawrylchak, Stéphane Herbet, Janet Hinshaw, Rüdiger Holz, Norbert Höser, Shannon Kenney, Mary LeCroy, Georges Lenglet, Vladimir Loskot, Herbert Lutz, Brigitte Massonneau, Julia Matthews, Gerald Mayr, Brad Millen, Jiří Mlíkovsky, Nigel Monaghan, Bernd Nicolai, Dominique Nitka, Patrick O’Sullivan, D. Stefan Peters, Matthieu Pinette, Alison Pirie, Robert Prys-Jones, Josef H. Reichholf, Julian Reynolds, Nate Rice, Douglas Russell, Frank Steinheimer, Paul Sweet, Ray Symonds, Claire Voisin, Damien Walshe, Michael Walters, Marie-Dominique Wandhammer, Erich Weber, and David Willard.