The Dance of Reality: A Psychomagical Autobiography (2 page)

Read The Dance of Reality: A Psychomagical Autobiography Online

Authors: Alejandro Jodorowsky

Tags: #Autobiography/Arts

I wanted to explain to Jaime that it was I who had suggested this much-needed remedy for the unfortunate man, but he would not let me speak. “Be quiet, and don’t let those abusive bums take advantage of you! Don’t ever get near them; they’re covered with lice that spread typhus!”

Indeed, the world is a fabric of suffering and pleasure; in every action, good and evil dance together like a pair of lovers.

Today, I still have no idea why I embarked on this folly: one day I got out of bed saying that I would not go out in the street unless I had red shoes. My parents, accustomed to having an unusual son, urged me to be patient. Such footwear was not to be found in the small shoe shop in Tocopilla. They were more likely to be found in Iquique, a hundred kilometers away. A traveling salesman agreed to take my mother, Sara Felicidad, to that large port city in his automobile. She returned smiling, bringing with her a cardboard box containing a fine pair of red boots with rubber soles.

Putting them on, I felt as if wings were sprouting from my heels. I ran to school, taking agile leaps along the way. I did not mind the torrent of mockery from my classmates, I was used to that. The only one who applauded my taste was the good Mr. Toro. (Did my desire for red shoes come directly from the Tarot? In it, the Fool, the Emperor, the Hanged Man, and the Lovers all wear red shoes.) Carlitos, my desk mate, was the poorest of all the children. After school he would sit on benches in the town square, equipped with a little box, and offer shoe-shining services. It embarrassed me to have Carlitos kneel at my feet, brushing my shoes, applying color and polish to make the dirty leather shine again. But I had him do it every day in order to give him the opportunity to earn a little money. When I placed my red shoes on his box, he gave a cry of joy and admiration. “Oh, those are so nice! It’s lucky I have red dye and neutral polish. I’ll make them shine like they’re varnished.” And for almost an hour he slowly, carefully, profoundly, caressed what for him were two sacred objects. When I offered him money, he did not want to accept it. “I’ve made them so shiny you’ll be able to walk in the night without needing a lantern!” Enthused, I began to admire my splendid boots while running around the square. Carlitos furtively wiped away a tear or two, murmuring, “You’re lucky, Pinocchio, I’ll never be able to have a pair like that.”

I felt a pain inside my chest, and I could not take another step. I took the shoes off and gave them to him. The boy, forgetting my presence, hastily put them on and took off running toward the beach. He forgot not only me, but also his box. I kept it, intending to give it to him the next day at school.

When my father saw me return home barefoot, he was furious. “You say you gave them to a shoe shiner? Are you crazy? Your mother went a hundred kilometers out and a hundred kilometers back to buy them for you! That brat’s going to come back to the square looking for his box. Go there, wait for him as long as it takes, and when he shows up, take your shoes back, by force if you need to.”

Jaime used intimidation as a method of education. The fear of being clobbered by his trapeze artist’s muscles made me break out in a cold sweat. I obeyed. I went to the square and sat down on a bench. Five interminable hours passed. As night was falling, a group of people came running along, surrounding a bicyclist. The man was pedaling slowly, leaning down as if an enormous weight was breaking his back. Bent double over the handlebars, like a marionette with cut strings, was the dead body of Carlitos. Through the rips in his clothing I could see his skin, formerly brown, now as pale as my own. His limp legs swung with each pedal stroke, drawing red arcs in the air with my boots. Behind the bicycle and the curious group of mourners, a rumor was fanning out like a ship’s wake. “He was playing on the slippery rocks. The rubber soles on his shoes made him slip. He fell into the sea and was battered against the rocks. That’s how the imprudent boy drowned.” Imprudent he may have been, but it was my generosity that killed him. The next day, everyone at the school went to lay flowers at the site of the accident. On those precipitous rocks, pious hands had built a miniature chapel out of cement. Inside it was a photograph of Carlitos and the red shoes. My classmate, having departed this world too early, without accomplishing the mission that God gives to every incarnated soul, had become an

animita

(little soul). Trapped in this state, he was now devoted to bringing about the miracles that believers requested of him. Many candles were lit behind the magical shoes that had once brought death but were now dispensers of health and prosperity.

Suffering, consolation; consolation, suffering. The cycle has no end. When I brought the shoe shiner’s box to his parents they hastily placed it in the hands of Luciano, the youngest brother. That same afternoon, the boy began shining shoes in the town square.

The fact is that during this era, when I was a child of an unknown race (Jaime did not call himself a Jew, but a Chilean son of Russians), no one ever spoke to me outside of books. My father and mother, at work in the shop from eight in the morning until ten at night, put their faith in my literary abilities and left me to educate myself. And what they saw I could not do for myself, they asked the Rebbe to do.

Jaime knew very well that his father, my grandfather Alejandro, had been expelled from Russia by the Cossacks, arriving in Chile not by his own choice but only because a charitable society shipped him where there was room for him and his family. Completely uprooted, speaking only Yiddish and rudimentary Russian, he descended into madness. In his schizophrenia he invented the character of a Kabbalist sage whose body had been devoured by bears during one of his voyages to another dimension. Laboriously making shoes without the aid of machinery, he conversed constantly with his imaginary friend and master. When he died, Jaime inherited this master. Even though Jaime knew full well that the Rebbe was a hallucination, the effect was contagious. The specter began to visit him each night in his dreams. My father, a fanatical atheist, endured the invasion of this character as a form of torture and did his best to exorcise the phantom—by stuffing my head full of it as if it were real. I was not taken in by this ploy. I always knew that the Rebbe was imaginary but Jaime, perhaps thinking that by naming me Alejandro he had made me as crazy as my grandfather, would tell me, “I don’t have time to help you with that homework, go ask the Rebbe,” or more often still, “Go play with the Rebbe!” This was convenient for him because in his misinterpretation of Marxist ideas he had decided not to buy me any toys. “Those objects are the products of the evil consumer economy. They teach you to be a soldier, to turn life into a war, to believe that all manufactured things are a source of pleasure through having miniature versions of them. Toys turn a child into a future assassin, an exploiter, not to mention a compulsive buyer.” The other boys had toy swords, tanks, lead soldiers, train sets, stuffed animals, but I had nothing. I used the Rebbe as a toy, lending him my voice, imagining his advice, letting him guide my actions. Later, having developed my imagination, I expanded my animated conversations. I endowed the clouds with speech, as well as the rocks, the sea, some of the trees in the town square, the antique cannon outside the city hall, furniture, insects, hills, clocks, and the old people with nothing left to wait for who sat like wax sculptures on the benches in the town square. I could speak with all things, and everything had something to say to me. Assuming the point of view of things outside of myself I felt that all things were conscious, that everything was endowed with life, that things I considered inanimate were slower entities, that things I considered invisible were faster entities. Every consciousness had a different velocity. If I adapted my own consciousness to these speeds, I could initiate rewarding relationships.

The umbrella that lay in a corner, covered with dust, lamented bitterly, “Why did they bring me here, where it never rains? I was made to protect from rain, without it I have no purpose.” “You’re wrong,” I told it. “You still have a purpose; if not at present, at least in the future. Show me patience and faith. One day it will rain, I assure you.” After this conversation a storm broke for the first time in many years, and there was a real deluge that lasted for a whole day. As I walked to school with the umbrella finally open, the raindrops came down with such force that its fabric was shredded in no time. A hurricane-force wind tore it from my hands and carried it in tatters off into the sky. I imagined the pleasant murmurings of the umbrella as it became a boat and happily navigated toward the stars after traversing the storm clouds . . .

Yearning hopelessly for some affectionate words from my father, I dedicated myself to observing him, watching his actions as if I were a visitor from another world. Having lost his father at the age of ten and needing to support his mother, brother, and two sisters, who were all younger than him, he had abandoned his studies and begun hard work. He could barely write, could read with difficulty, and spoke Spanish in a manner that was almost guttural. Actions were his true language. His territory was the street. A fervent admirer of Stalin he wore the same style of mustache, fashioned with his own hands the same kind of stiff-collared coat, and cultivated the same affable mannerisms behind which an infinite aggressiveness was concealed.

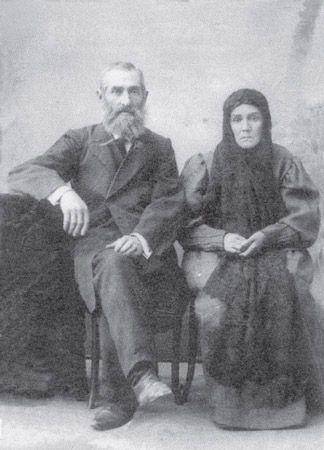

My paternal great-grandparents.

Fortunately, my maternal grandmother’s husband Moishe, who had lost his fortune in the stock market crash but still kept a little shop as a gold dealer, bore a resemblance to Gandhi due to his bald head, missing teeth, and large ears; this balanced things out. Fleeing the severity of the dictator, I took refuge at the knees of the saint. “Alejandrito, your mouth was not made for saying aggressive things; every hard word dries up your soul a little bit. I shall teach you to sweeten your words,” he said. And after painting my tongue with blue vegetable dye, he took a soft-haired brush a centimeter wide, dipped it in honey, and made as if to paint the inside of my mouth. “Now your words will have the color of the blue sky and the sweetness of honey.”

In contrast, for Jaime/Stalin life was an implacable struggle. Unable to slaughter his competitors, he ruined them instead. Casa Ukrania was an armored tank. Since the main street (Calle 21 de Mayo, named for a historic naval battle in which the hero Arturo Prat had turned his defeat at the hands of the Peruvians into a moral triumph) was lined with shops selling the same articles he was selling, he employed an aggressive sales tactic. He declared, “Abundance attracts the buyer; if the seller is prosperous that suggests that he is offering the best goods.” He filled the shelves of the shop with boxes, a sample of the contents sticking out of each box: the tip of a sock, the fold of a stocking, the cuff of a shirtsleeve, the strap of a brassiere, and so on. The store appeared to be full of merchandise, which was not the case, for each box was empty save for the item that was poking out.

In order to awaken customers’ desires he organized items into various lots rather than selling them separately and exhibited collections of things in cardboard boxes. For example, a pair of underwear, six drinking glasses, a clock, a pair of scissors, and a statuette of Our Lady of Mount Carmel; or a wool vest, a piggy bank, some lace garters, a sleeveless shirt, a communist flag, and so forth. All the lots had the same price. Like me, my father had discovered that all things are interrelated.

He hired exotic propagandists to stand in the middle of the sidewalk in front of the door. There was a different one every week. Each one, in his or her own way, would loudly extol the quality and low price of the articles for sale, inviting curious passersby to step inside Casa Ukrania, under no obligation to buy anything. They included, among others, a dwarf in a Tyrolean costume, a skinny man dressed as a nymphomaniacal black woman, a Carmen Miranda on stilts, a wax automaton who beat at the shop windows from the inside with a cane, a ghastly mummy, and a stentorian whose voice was so loud that his shouts could be heard a kilometer away. Hunger created artists; the out-of-work miners invented all sorts of disguises. They would make Dracula or Zorro costumes out of flour sacks from the mill that they had dyed black; masks and warrior’s capes from debris found in garbage cans. One of them brought along a mangy dog dressed in Chilean peasant clothes that danced on its hind paws; another brought a baby that cried like a seagull.