The Dangerous Book of Heroes (5 page)

Read The Dangerous Book of Heroes Online

Authors: Conn Iggulden

In 2003, Fiennes had a heart attack and endured a double bypass operation. Months later, he wanted to raise money for the British Heart Foundation and planned a series of seven marathons in seven days on seven continents. At the time, he asked his doctors whether such activity would put too much strain on his heart. They replied that they had no ideaâno one had ever tried such a thing before. In November of that year he completed all seven with his running partner, Mike Stroud.

In 2005 he came to within a thousand feet of the peak of Everest. He tried again in 2008, at age sixty-four, but bad weather and exhaustion overcame him.

One of the strangest things about him is that despite the similarities to other heroes in this book, Fiennes is always understated, softly spoken, and modest about his achievements. He is certainly a man driven to push himself to extraordinary lengths, to such a degree that

he becomes not so much an inspiration as a force of nature. His attitudes to trials and hardship are a pleasant antidote to some of the touchy-feely aspects of modern society. In short, he is not the sort of man to whom the “compensation culture” caters. We do need such men, if only to highlight the silliness of some of the other sort.

Recommended

Living Dangerously and Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Know

by Ranulph Fiennes

R

ichard Francis Burton was born in Devon, England, in 1821. Victoria came to the British throne in 1837, when he was just sixteen, so he was in some ways the archetypal Victorian scholar-adventurer. In his life, he was a soldier, a spy, a tinker, a surveyor, a doctor, an explorer, a naturalist, and a superb fencer. As an under-cover agent, he was instrumental in provinces of India coming under British control, playing what Kipling called “the Great Game” with skill and ruthlessness. In recent times, Burton was one of the inspirations for Harry Flashman in the books by George MacDonald Fraser.

Burton spoke at least twenty-five languages, some of them with such fluency that he could pass as a native, as when he disguised himself as an Afghan and traveled to see Mecca. He spent his life in search of mystic and secret truths, at one point claiming with great pride that he had broken all Ten Commandments. In that at least, he was not the classic Victorian adventurer at all. Burton always went his own way. When he was asked by a preacher how he felt when he killed a man, he replied: “Quite jolly, how about you?”

At various points in his life, he investigated Catholicism, Tantrism, a Hindu snake cult, Jewish Kabbalah, astrology, Sikhism, and Islamic Sufism. He was convinced that women enjoy sexual activity as much as men, a very unfashionable idea in Victorian England. He enjoyed port, opium, cannabis, and khat, which has a priapic effect. He was six feet tall, very dark, and devilishly handsome, with a scar from a Somali spear wound on his cheek that seemed only to add to his allure. In short, he was a romantic and a devil, a dangerous man in every sense.

After Richard was born, his parents moved to France in an attempt to ease his father's asthma. Two more children were born to

them there: Maria and Edward. Richard showed a remarkable facility for languages from an early age, beginning Latin at the age of three and Greek the following year.

The two boys were also taught arms as soon as they could hold a sword. They thrived on rough play and, at around the age of five, knocked their nurse down and trampled her with their boots. They fought with French boys and were constantly beaten by their father, but to little effect. Their tutor took all three children to see the execution by guillotine of a young Frenchwoman. This did not produce nightmares, however, and the children later acted out the scene with relish.

At the age of nine, Richard used his father's gun to shoot out the windows of the local church. He lied, stole from shops, and made obscene remarks to French girls. His appalled father realized that France was not producing the young gentlemen he had wanted, so he packed up and took the family back to England.

At home, Richard made new enemies at school, until at one point he had thirty-two fights to complete. In frustration, the senior Burton decided to take his family back to France. They settled at Blois, where the children were taught by a Mr. Du Pré and a small staff. They learned French, Latin, Greek, dancingâand, best of all, fencing. Both boys excelled with foils and swords.

It was perhaps their father's restless spirit that would infect Richard with the desire for constant movement. From Blois they went to Italy, where Richard learned the violin until his master said that while the other pupils were beasts, Richard was an “archbeast.” In reply, Richard broke the instrument over the master's head.

The family moved on to Siena, then Naples, where the boys learned pistol shooting, cockfighting, and heavy drinking. Cholera swept Naples, and out of ghoulish curiosity, Richard and Edward dressed as locals and helped to remove the dead to the plague pits outside the city. They also discovered prostitutes and spent all their pocket money on them.

From a young age, the brothers were determined to enter the military. Their father was equally determined that they become clergymen.

To that end, he sent Richard to Oxford University and Edward to Cambridge, splitting them up for their own safety. Other tutors were engaged, and it was then that Richard met Dr. William Green-hill, who spoke not only Latin and Greek fluently but Arabic as well.

Despite his delight in languages, Burton disliked Oxford intensely. He attempted to arrange a duel on his first day, only to be ignored. He said later that he felt he had fallen among grocers. He hated the food, the beer, and the monotony. Annoyed by the hostility toward his dark and foreign appearance, he kept his door open but left a red-hot poker in the fireplace to repel unwanted visitors. He became determined to have himself expelled and broke every rule he could find, but at first the university ignored his excesses. Over the winter holidays in London, Richard and Edward met the sons of a Colonel White, from whom they heard tales of service in India and Afghanistan, where British forces had recently been defeated with great losses. Burton redoubled his efforts to be thrown out of Oxford, going to a horse race after being forbidden to attend. Called before the university authorities, Burton launched into a long speech about morality and trust and showed no remorse. He was expelled at last and left Oxford riding on a tandem-driven dog cart, blowing a coaching horn.

Burton's father was appalled and furious but, recognizing the inevitable, allowed both his sons to join the East India Company army. Edward was posted to Ceylon, now known as Sri Lanka, while Burton was posted to the subcontinent itself.

Warned of the heat in India, Burton shaved his head and bought a wig as well as learning Hindustani. During the voyage, he boxed, fenced, and practiced his language skills. By the time he landed in India, he was almost completely fluent. He did not know it then, but he was about to begin a relationship with the subcontinent that would provide a driving force to his previously aimless life.

It did not begin well. Burton fell ill with diarrhea and spent time in a sanatorium. He disliked the smell of curry and the lack of privacy in the company rooms. He began to learn Gujerati and Persian, ignoring the distressing presence of a crematorium next door, of which

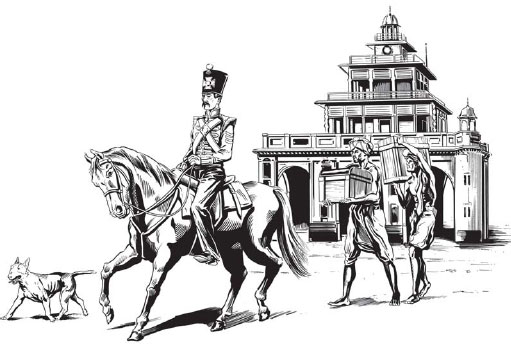

he said, “The smell of roast Hindu was most unpleasant.” He found the tiny society of five hundred Europeans stifling, though he enjoyed the brothels and bazaars. For almost two months he endured, then he was sent at last to his first posting, at Baroda. He took a horse, servants, a supply of port, and a bull terrier with him. He was slowly falling in love with India, in all its endless variety.

Baroda was a baking-hot maze of alleys and exotic sights, with summer temperatures up to 120° F. The lives of the inhabitants were brutal, with appalling punishments for misdeeds, such as placing a criminal's head beneath an elephant's foot to be crushed. Burton loved it, from the strange smells of incense, hashish, and opium to the courtesans, shrines, alien flowers, and colorful mosques. Of the white officers, he said: “There was not a subaltern in the 18th Regiment who did not consider himself capable of governing a million Hindus.” He took a temporary native wife, whom he described as his “walking dictionary,” and found the courtesans more playful and less inhibited than their frosty counterparts in England. He threw himself into an exploration of sexual matters that would inform his writings many years later. Hunting and hawking kept him busy for a while, but he quickly lost the taste for it. He kept a company of monkeys, who ate at the table with him. He won the regimental horse race, learned the Indian style of wrestling, and taught his troops gymnastics to keep them agile.

In 1843, Burton took government examinations in Hindustani and made first in his class. He so successfully immersed himself in a Hindu snake cult that he was given the

janeo,

the three-ply cotton cord that showed he was a Brahmin, the highest caste. This was a unique event, unheard of before or since. In all other cases, a Hindu had to be born into that religion and only attained the highest caste after millennia of reincarnation. This honor came despite the fact that he remained a meat eater and is the more astonishing for it. He went on to discover Tantrism, with its philosophy, as he wrote, “not to indulge shame or adversion to anythingâ¦but freely to enjoy all the pleasures of the senses.”

He attended Catholic chapel, then later converted to Islam and

then Sikhism, in love with the mysticism of all faiths and throwing himself into one until he found himself drawn to the next. He was not a dilettante, however. In each case, he searched and learned all he could and completed every ritual with steadfast determination and belief, yet somehow his soul wandered as much as his feet and there were always new towns to see.

In 1843, Burton became the regimental interpreter for the Eighteenth Bombay Native Infantry and moved to Bombay (now Mumbai), bound for Karachi to join General Charles Napier and the British forces fighting in Sindh. Napier recognized Burton's abilities and used him in a variety of diplomatic missions through 1844 and 1845. Many of the details have been lost, but Burton became indispensable, a man who could fight or talk his way out of anything. He became used to traveling in disguise, and his contemporaries whispered that he had “gone native.” In 1845, when Burton was just twenty-four, Napier sent him to infiltrate and report on a male brothel. Burton wrote of what he saw in such grisly detail that his many enemies suggested he had taken part in the activities he witnessed. There is, however, no evidence for this, and in fact Burton was always scathing about “le Vice,” as he called it. Napier had the brothel destroyed after reading the reports, and it is worth pointing out that the

famously straitlaced general lost no confidence in his agent as a result of this mission.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

Away from the society of Britons in India, Burton became more and more of an outsider. He wore native clothing constantly, complete with turban and loose cotton robes. His experience of different faiths meant that he could work as a spy among Muslims or Hindus with equal invisibility. He also had himself circumcised so that his disguise would be foolproof even while bathing. In the Indus Valley, he found remnants of Alexander the Great's forts, as well as far more ancient ruins. He soaked it all up into his prodigious memory and delighted in fables and stories wherever he traveled for Napier. His reports were often inflammatory, and he complained constantly that the English did not understand the natives. Napier, for example, tried to make punishments humane, and thus they lost their effect on a people used to brutal rulers. Instead of cutting off a hand for stealing, the English merely imprisoned a man, who then thought them effete. Napier also issued a proclamation that he would hang anyone who killed a woman on suspicion of unfaithfulness, as was common in Sindh at that time. Burton may have had a personal reason to resent this practice, as his own affair with a high-born Persian woman came to an abrupt and possibly violent end, though details are sketchy.

When Burton was not working, he endured the hottest months, took notes, and drew everything he saw. He was always prolific and either wrote or translated more than fifty books in his time, on subjects ranging from the history of sword making to the strange places and people he saw. He was the first white man to publish details of the Islamic Sufi sect, which he threw himself into with his usual ferocious enthusiasm.

In 1845, suspecting that the British were about to annex the Punjab, a Sikh army crossed into British-held territory. It was a short war but hard fought, and by 1846, the Sikhs were brought to the negotiating table. The Punjab came under British rule. Around this time, Burton became ill with cholera and recovered very slowly. During his sick leave, he explored the Portuguese colony at Goa. He

left his regular mistress behind in Sindh and spent some time trying to get a nun out of a local convent to be his next one. In one attempt, he visited the wrong room in the night and found himself being chased by an elderly nun. He pushed her into a river as he made his escape.

In the company of Englishwomen, he found himself a man apart, almost unable to communicate or remember the strict rules of contact and flirtation. In the end, he managed to find another “temporary wife.” By this time, Burton dressed and acted as a man of the East rather than the West and had been made very dark by the constant sun. He continued to study Sufism but around 1847â8 also had himself inducted into Sikhism, a “conversion” that was never likely to last long with this firebrand of a man.