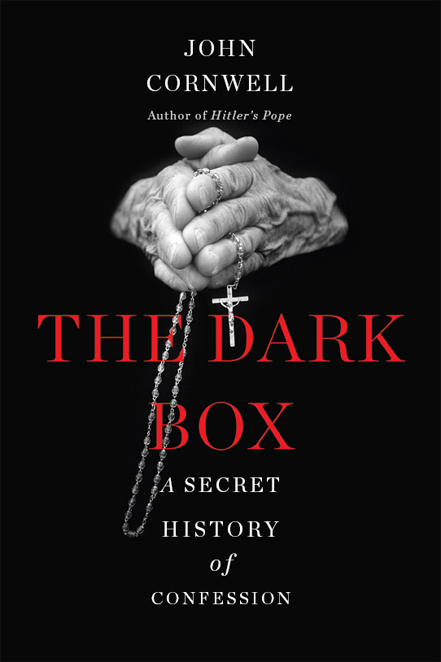

The Dark Box: A Secret History of Confession

Read The Dark Box: A Secret History of Confession Online

Authors: John Cornwell

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #Catholic, #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Christian Rituals & Practice, #Sacraments

THE DARK BOX

ALSO BY

JOHN CORNWELL

Nonfiction:

Coleridge: Poet and Revolutionary

A Free and Balanced Flow

(with Colin Legum)

Earth to Earth

A Thief in the Night

The Hiding Places of God (Powers of Darkness, Powers of Light)

Nature’s Imagination

(ed.)

The Power to Harm

Consciousness and Human Identity

(ed.)

Hitler’s Pope

Breaking Faith

Explanations

(ed.)

Hitler’s Scientists

The Pontiff in Winter

Seminary Boy

Darwin’s Angel

Philosophers and God

(ed. with Michael McGhee)

Newman’s Unquiet Grave

Meditations of Samuel Taylor Coleridge

(ed.)

Fiction:

The Spoiled Priest

Seven Other Demons

Strange Gods

Copyright © 2014 by John Cornwell

Published by Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail

[email protected]

.

Scripture quotations are from the Holy Bible, Revised Standard Version, Containing the Old and New Testaments with the Apocrypha / Deuterocanonical Books: An Ecumenical Edition. New York: Collins, 1973.

Designed by Pauline Brown

Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by the Perseus Books Group

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cornwell, John, 1940–

The dark box : a secret history of confession / John Cornwell.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-465-08049-6 (e-book) 1.

Confession—History. I.

Title.

BV845.C67 2014

264'.0208609—dc23

2013042961

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of

Peter Carson

1938–2013

Editor, Publisher, Friend

I was so full of joy, submitting and humbling myself before the confessor, a simple, timid priest, and exposing all the filth of my soul;

I was so full of joy at my thoughts merging with the aspirations of the fathers who wrote the ritual prayers;

I was so full of joy to be one with all believers, past and present . . .

—Leo Tolstoy,

Confession

, translated from the Russian by Peter Carson, 2013

CONTENTS

PART ONE: A BRIEF HISTORY OF CONFESSION

One:

Early Penitents and Their Penances

Three:

Confession and the Counter-Reformers

Four:

Fact, Fiction, and Anticlericalism

Five:

The Pope Who ‘Restored’ Catholicism

Seven:

The Great Confessional Experiment

Eight:

The Making of a Confessor

Ten:

Sexual Abuse in the Confessional

Twelve:

Varieties of Confessional Experience

W

HEN

I

BEGAN RESEARCH FOR THIS BOOK,

I

ASKED

C

ATHOLIC

friends: ‘How long since your last confession?’ I heard ‘twenty years’, ‘thirty years’, and an occasional ‘two months’. Sometimes I was told ‘Mind your own business’. It seems only right to state my own circumstance from the outset.

Brought up after the Second World War in London’s East End by a devout mother of Irish extraction, I was instructed in the Catholic faith by nuns from the age of five. I made my first confession at age seven, the day before my first communion. On Saturday afternoons or evenings, all the family, including four siblings, joined the lengthy queues at our local church to confess our sins—all except my father, that is, who only became a Catholic to marry my mother.

In confession, as we were taught, you started by telling the priest how many weeks or months had elapsed since your last confession. You listed the sins committed since that last confession, then said a prayer of contrition. The priest would ask some questions to clarify the nature of the sins you had told him. He might also offer spiritual advice. You were obliged to feel genuinely sorry for having offended God, and

to declare that you would try not to commit those sins again. If it was possible to make reparation to the people you had wronged, it was important to do so. The priest then imposed a penance—usually a few prayers—and said the words of absolution. We were told that absolution relieved us of the guilt for the sins we had confessed. We were taught that in the case of a mortal sin (a grave sin deserving of Hell), absolution lifted the dire penalty of eternal punishment. Nowadays, Catholics are commonly told that absolution reconciles them to God’s love.

My father was convinced, like many non-Catholics, that confession allowed Catholics to commit sins, have them forgiven (and feel good), then commit them again. As a well-taught Catholic, I knew better. Absolution did not work unless you had a ‘firm purpose of amendment’. That determination, we realised, was as fragile as human nature itself.

I served Mass at our local church every morning from the age of ten. At age twelve I admitted to our parish priest that I wanted to be like him—a priest. In retrospect, this was odd, for Father James Cooney—austere, desiccated, humourless—was hardly an attractive role model. My mother said that going to confession with him was like ‘going on trial for your life’. But I had fallen in love with the ritual of the Mass and would spend hours in the privacy of my bedroom bobbing up and down before a makeshift altar, muttering mumbo-jumbo pretend Latin. The following year I was enrolled in a junior seminary—a monastic boarding school for boys, 150 miles from home, where I was to spend five years receiving a privileged

education, including Latin and Greek, in preparation for senior seminary.

I got on well with most of our priest-teachers, who worked hard to bring us to a high standard of education. They were generally kind men and exemplary models of priesthood. One day, however, I was sexually propositioned by one of our priests while he was hearing my confession. I realised that externals of clerical piety are no guarantee of authentic holiness. I would never again enjoy unalloyed trust in the beneficence of priests, especially in confession. I nevertheless proceeded at eighteen to the senior seminary, where I stayed long enough to complete the course in philosophy of religion and experience the rigorous priestly formation of that era, including instructions that would shape a future confessor. I was becoming a ‘Catholic cleric’. My vocation had become a matter of habit rather than choice. I had confessed every week of my life—from boyhood to the age of twenty-one.

After seven years of seminary life, junior and senior, I came to see that the priesthood was not for me. I knew in my heart of hearts, and in my genitals, that I would not make it as a celibate. Catching up with the world—music, dancing, girls, lay clothes, making my own decisions after years of seminary discipline—was not easy. My understanding tutor at Oxford, where I had arrived to study English literature, quipped one day: ‘My dear fellow, you need to learn in life how to take the smooth with the rough . . .’

I became convinced that Catholicism, for me at least, was not an impetus for maturity and happiness. At the same time,

I was finding it difficult to reconcile Christianity with an increasingly positivist, scientific view of the world. As a graduate student at Cambridge, I finally, consciously, abandoned my Catholicism. For the next twenty years I would hover between atheism and agnosticism. But time, my dream life, and a gradual appreciation of the difference between religious imagination and magic realism opened the way to at least consider the

possibility

of a God after atheism.

Marriage to a devout Catholic who brought up our children in the faith, and nostalgia for the rhythms of Catholic liturgy, prompted a change of heart—not so much a return as a progression—although I remain circumspect. Notions of a vengeful God have been difficult to exorcise entirely. To this day, moreover, I have occasional, inchoate suspicions that these renewed quests for a once-rejected God mask a search for the lost abusers of one’s childhood. This book, however, while written from the inevitable perspective of an individual member of the Catholic faithful, draws on a wide range of historical sources and the personal testimonies of fellow Catholics past and present.

I

N THE EARLY PERIOD OF THE

C

HRISTIAN CHURCHES

, penitents would confess in public those major sins that had excluded them from their communities—such as murder, idolatry, and adultery. The ritual of reconciliation into the community or congregation was seldom allowed more than once in a Christian’s lifetime. It was not until the Middle Ages that all adult members of the faithful within Latin Christianity were obliged to tell their sins to a priest in private once a year. The penitent would kneel before the seated confessor, with the possibility of physical contact between the two. The practice of Roman Catholics entering a dark box to confess their sins did not begin until the mid-sixteenth century, following the Reformation and the fragmentation of Western Christendom.

The confessional box is a booth-like piece of church furniture containing a dividing panel. This panel physically separates the penitent, who kneels in the dark, from the confessor, who sits in the light. There is a grille set in the panel that allows for verbal communication; in theory, it obscures the faces of penitent and confessor from each other. Although

most devout Catholics born before 1970 used to enter that box frequently, Catholic confession, whether inside the box or outside it, has been largely abandoned, despite pleas from the previous pope, Benedict XVI, and many of the world’s bishops to revive the practice.