The Day We Went to War (39 page)

Read The Day We Went to War Online

Authors: Terry Charman

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Military, #World War II, #Ireland

There were genuine German air raids on Britain during the first months of what was soon to become known as the ‘Phoney War’. But they too were confined to attacks on British warships rather than land targets. The first came on Monday, 16 October. Royal Navy ships were attacked in the Firth of Forth near Edinburgh. Peter Walker, Provost of South Queensferry, witnessed the raid from his house, just two miles away from the scene of the action:

‘I heard a terrific explosion, and saw a great waterspout rising from the river into the air. A bomb was released and I could plainly see it fall. More ’planes came over. A terrible hail of shells went up from the anti-aircraft batteries. It seemed as if the raiding aircraft reeled. Then they seemed to recover. Numbers of bombs fell – but all dropped into the water. It seemed impossible that the ’planes could live in the barrage of shrapnel put up by the anti-aircraft guns. A shot struck one ’plane and I saw part of the machine fall into the Firth.’

Its crew were picked up by John Dickson’s fishing vessel

Day Spring

. His son, John Junior, helped with the rescue:

A Heinkel He IIIH bomber brought down at Long Newton Farm, Humbie, near Edinburgh, 28 October 1939. Of the four-man crew, two died and two were captured. A London clerk was overheard to say, ‘I hope they don’t start getting very fierce, just yet. I don’t feel like being bombed: I’d be ever so scared if they did come.’

‘We threw ropes to the crew of the sinking ’plane, and when we hauled them on board we discovered that they were all three wounded. They told us that another member of the crew had gone down with the ’plane. They were all young chaps. The man who appeared to be the senior had a bad eye injury. Another had been shot in the ribs and we stretched him out on the deck. The third man had been shot in the arm and it was broken. The three men were very grateful for being rescued, and the leader, who spoke English fairly well, took a gold signet ring from his finger and gave it to my father . . . “This is a ring for saving me,” he said.’

The next day, the naval base at Scapa Flow was the target, and sporadic raids continued throughout the rest of the year. Casualties were negligible but as 1939 closed Major-General Charles Foulkes, an authority on civil defence and gas warfare, warned:

‘Of course, we must not assume that air raids are not a very real source of danger to this country. But public attention was, for a long time, confined to how they might be endured rather than how they might be met and defeated – an attitude which is not in harmony with the spirit that the nation has shown in its past history.’

C

HAPTER

7

The War on Land

On land, the Allied effort was not much more successful or indeed warlike than that in the air. The first units of the British Expeditionary Force started crossing over to France on 4 September, but the main effort began six days later. In five weeks, 158,000 men and their equipment were transported across the Channel without a single casualty, as war minister Leslie Hore-Belisha proudly announced to the Commons on 11 October. Their transports were covered with confident graffiti: ‘Look out Adolf, here we come!’, ‘Berlin or Burst!’ But, unlike their predecessors of 1914, ‘The New Contemptibles’, as the press dubbed them, did not immediately get to grips with the enemy. In fact it was not until 9 December that the first British soldier was killed in action. In his (illegal) diary entry for that day, Second Lieutenant Alec Pope of 1st Battalion, The King’s Own Shropshire Light Infantry, wrote:

‘A quiet day. Saturday night our fighting patrol ran into its own booby trap and were bombed and fired on by our ambush party. One man killed and five wounded. Max took out a Rescue Party through “D” Company lines and I acted as Covering Party. My

covering patrol left out by mistake – reported “missing” – but we all fetched up safely . . .’

The man killed was twenty-seven-year-old regular soldier Corporal Thomas Priday, the son of Allen Priday and his wife Elizabeth of Redmarley in Gloucestershire. Priday’s funeral at Luttange Communal Cemetery was an Anglo-French occasion, with a French honour guard and the local corps commander present. Such occasions were seen as necessary to shore up the military

Entente Cordiale,

and to counteract German propaganda, which was forever harping on that Britain would fight to the last Frenchmen. The day before Corporal Priday was killed, Alec Pope had picked up a German propaganda leaflet shaped like an autumn leaf. Its message in French read:

‘Autumn. The leaves fall. We shall also fall. Leaves fall because God so wishes it. But we fall because the English wish it. Next spring no one will remember either the dead leaves or the soldiers who are killed. Life will pass on over our graves.’

These leaflets and the propaganda broadcasts of French fascist Paul Ferdonnet, ‘The Traitor of Stuttgart’, undoubtedly had their effect on sapping morale among the

poilus

that autumn. Not that General Gamelin’s forces were doing much fighting themselves. A secret military convention concluded with the Poles in May 1939 had agreed that ‘from the moment the bulk of the German forces marched against Poland, France would launch an offensive against Germany, putting in all her available forces from the fifteenth day after mobilisation’. Even before that date, Gamelin had agreed to both the French

Armée de l’Air

launching air attacks and land forces undertaking, ‘a series of offensive actions against limited objectives’.

But despite desperate entreaties from the beleaguered Poles, Gamelin limited his action in September to the so-called ‘Saar Offensive’. Only nine divisions out of the eighty-five on France’s north-eastern front were involved, and there was no Allied air activity apart from a few reconnaissance flights over the Siegfried Line. But in both the French and British media the ‘offensive’ was presented in a grossly exaggerated terms. The press and newsreels were full of images of French troops ‘triumphantly’ advancing through German villages towards the Siegfried Line.

The Times

claimed that French forces were in occupation of 100,000 acres of German territory, which sounded a considerable achievement. In reality, it was just about twenty-one square miles.

The two Allied commanders-in-chief, Lord Gort VC

(left)

with General Maurice Gamelin, photographed in October 1939.

Men of the British Expeditionary Force disembarking in France, September 1939. The first fighting troops started to land on 10 September. To the consternation of the British censor,

Daily Express

reporter Geoffrey Cox broke the news two days later. This led to the seizure of the edition which featured Cox’s story.

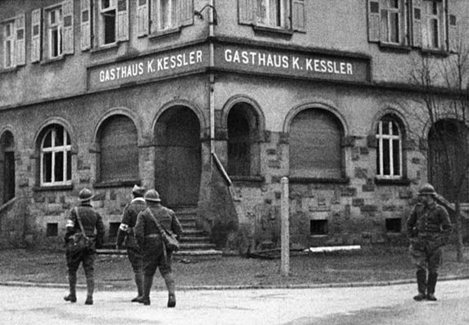

French troops in a captured German village during Gamelin’s Saar ‘offensive’ on the Western Front. ‘More than half of our active divisions on the north-east front are engaged in combat. Beyond our frontier the Germans are opposing us with a vigorous resistance.’

Back in Huddersfield, Marjorie Gothard wrote in her diary on 15 September: ‘French troops have cut off Saarbrucken and dominate communications with the German interior. High points all round the town are held by the French. It is now certain that Saarbrucken will fall to the French and enable the army to proceed straight to the main forts of the Siegfried Line.’

The next day, she noted that the ‘news’ was even better: ‘The French have seized dozens of German villages, their grip is tightening like a vice around Saarbrucken, the fall of which is considered imminent.’

But even as Marjorie was writing up her diary, Gamelin had already decided to call off the ‘offensive’. In a letter to the Polish military attaché, he had made extravagant claims about its success. ‘We know,’ he untruthfully told the Pole, ‘we are holding down before us a considerable part of the German air force.’ Furthermore, ‘prisoners indicate the Germans are reinforcing their battle-front with large new formations’. In reality, not a single German soldier, tank, or plane was diverted from Poland to reinforce the Western Front. The French began to withdraw the bulk of their troops from the ‘conquered’ territory on 30 September. It was done much to the annoyance of Premier Daladier who feared ‘the reaction of public opinion not only in France, but throughout the world’. The withdrawal was completed on 4 October, with only a light screening of French troops left in position. Ten days later, Gamelin, convinced that the Germans were about to launch a major

attack, issued a rousing order of the day. It was worthy of Napoleon himself:

‘Soldiers of France! At any moment a battle may begin on which the fate of the country will once more in our history depend. The nation and the whole world have their eyes fixed upon you. Steel your hearts! Make the best use of your weapons! Remember the Marne and Verdun!’

Two days later, on 16 October, the Germans duly attacked, but only in company or battalion strength. By evening the next day, at the cost of 198 casualties, they had regained every one of those 100,000 acres.

For the rest of the autumn and winter, the French and British settled down to a defensive war on the Western Front, with routine patrols and very limited local attacks. The newspapers were full of photographs of VIPs visiting the BEF and ‘human interest’ stories about Gort’s men, and how they were furthering the

Entente Cordiale.

Typical was that of one in December when British Bren gun carriers hauled a French wine merchant’s van out of a ditch. ‘So again,’ the caption read, ‘the soldiers of 1939 are giving practical proof that the alliance has something more than military significance.’ To those who complained about the lack of action, came a stern warning in a broadcast from Major-General Sir Ernest Swinton:

‘The war is not being run to provide news. And when I hear people complaining about the lack of news from France and talking about “All Quiet on the Western Front”, I say “Thank God that there

is

no news of battles; thank God that the commanders have learned something from 1914–1918, and that the Allied troops are not going to be thrown in haste, without due preparation, against a stone wall, or rather, a steel and concrete maze, bristling with every sort of gun.”’