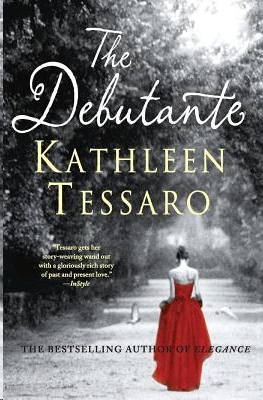

The Debutante

THE

DEBUTANTE

KATHLEEN TESSARO

For Annabel

Table of Contents

In the heart of the City of London, tucked into one of the

Cate walked up the steps of 1a Upper Wimpole Street, to

It was a very different journey to Endsleigh the second

There is a dangerous silence in that hour

A stillness, which leaves room for the full soul

To open all itself, without the power

Of calling wholly back its self-control:

The silver light which, hallowing tree and tower,

Sheds beauty and deep softness o’er the whole,

Breathes also to the heart, and o’er it throws

A loving languor, which is not repose.

L

ORD

B

YRON

,

Don Juan

Part One

In the heart of the City of London, tucked into one of the

In the heart of the City of London, tucked into one of the winding streets behind Gray’s Inn Square and Holborn Station, there’s a narrow passage known as Jockey’s Fields. It’s a meandering, uneven thread of a street that’s been there, largely unchanged, since the Great Fire. Regency carriages gave way to Victorian hackney cabs and now courier bikes speed down its sloping, cobbled way, diving between pedestrians.

It was early May; unseasonably hot — only nine in the morning and already seventy-six degrees. A cloudless blue sky set off the white dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in the distance. The pavement swelled with armies of workers, streaming from the nearby Tube station; girls in sorbet-coloured summer dresses, men in shirtsleeves, jackets over their arms, carrying strong coffee and newspapers, the rhythm of their heels a constant tattoo on the pavement.

Number 13 Jockey’s Fields was a lopsided, double-fronted Georgian building, painted black many years previously, and in need of a fresh coat, sandwiched between a betting office and a law practice. The door of Deveraux and Diplock, Valuers and Auctioneers of Quality, was propped

open by a Chinese ebony figure of a small pug dog, most likely eighteenth century but in very bad repair, in the hopes of encouraging a gust of fresh morning air into the premises. Golden shafts of sunlight filtered in through the leaded glass windows, dust floating, suspended in its beams, settling in thick layers on the once illustrious, now slightly shabby interior of one of London’s lesser known auction houses. The oriental carpet, a fine specimen of the silk hand-knotted variety of Northern Pakistan during the last century, was threadbare. The delft china planters which graced the mantelpiece, brimming with richly scented white hyacinth, were just that bit too chipped to be sold at any real profit; and the seats of the 1930s leather club chairs by the fireplace sagged almost to the floor, their springs poking through the horsehair backing. Reproduction Canalettos hung next to the better watercolour dabblings of long-dead country-house hostesses; studies of landscapes, flowers and fond attempts at children’s portraits. For Deveraux and Diplock was the natural choice of those once aristocratic families whose fortunes had lost pace with their breeding and who wished to have their heirlooms sold quickly and discreetly, rather than in the very public catalogues of Sotheby’s and Christie’s. They were known by word of mouth and reputation, having traded with the same European and American antique dealers for decades. Theirs was a dying art for a dying class; a kind of undertakers for antiquities, presided over by Rachel Deveraux, whose late husband Paul had inherited the business when they were first married thirty-six years ago.

Rachel, smoking a cigarette in a long, mother-of-pearl holder which she’d acquired clearing the estate of an impoverished 1920s film star, sat contemplating the mountain of paperwork on her huge, roll-top desk. At sixty-seven, she was still striking, with large brown eyes and a knowing, disarming smile. Her style was unorthodox; flowing layers of modern, asymmetrical Japanese-inspired tailoring. And she had a weakness for red shoes that had become a personal trademark over the years — today’s pair were vintage Ferragamo pumps circa 1989. Pushing her thick silver hair away from her face, she looked up at the tall, well-dressed man prowling the floor in front of her.

‘It will be fun, Jack.’ She exhaled; a long, thin stream of smoke rising like a spectre, floating round her head. ‘Think of her as a companion, someone to talk to.’

‘I don’t need help. I’m perfectly capable of doing it on my own.’

Jack Coates gave the impression of youth even though he was nearing his mid-forties. Slender, with elegant aquiline features, thick lashes framing indigo eyes, he moved with an animal grace. His dark hair was closely cropped, his linen suit well-tailored and pressed; yet underneath his polished exterior a raw, unpredictable energy flowed. He was a man straining at his own definition of himself. Frowning, he stopped, fingers drumming the top of the filing cabinet.

‘I prefer to do it alone. There’s nothing more tedious than talking to strangers.’

‘It’s a three-hour drive.’ Rachel leaned back, watching him. ‘She’ll hardly be a stranger by the time you arrive.’

‘I’d rather go on my own,’ he said, again.

‘That’s the trouble with you; you rather do everything on your own. It’s not good for you. Besides —’ she flicked a bit of ash into an empty teacup — ‘she’s very pretty.’

He looked up.

She arched an eyebrow, the hint of a smile on her lips.

‘What difference does that make?’ Jamming his hands into pockets, he turned away. ‘Perhaps I should point out that this isn’t some small turn-of-the-century Russian village and you’re not an ageing Jewish matchmaker eking a living out by tossing complete strangers together and adding a ring. We’re in London, Rachel. The millennium dawns. And I’m perfectly capable of doing the job I’ve been doing for the past four years on my own — without the assistance of young nieces of yours, fresh from New York, trailing round after me.’

She tried a different tack.

‘She’s an artist. She’ll be very helpful. She has an excellent eye.’

He snorted.

‘She’s had a difficult time of it lately.’

‘Which what, roughly translates to “she’s broken up with her boyfriend”? Like I said, I don’t need a companion. And especially not some moody art student who’ll spend the entire time on the phone, arguing with her lover.’

Stubbing out her cigarette, Rachel took out her reading glasses. ‘I’ve already told her she can go.’

He swung round. ‘Rachel!’

‘It’s a large house, Jack. Even with two of you, it will take you days to value and catalogue the whole thing. And whether you deign to acknowledge it or not, you need help. You don’t have to talk to her at length or share the contents of your innermost heart. But if you can manage to be civil, you might just notice that it’s actually nicer not doing everything on your own.’

He paced like a caged animal. ‘I can’t believe you’ve done this!’

‘Done what?’ She looked at him hard over the top of her glasses. ‘Hired an assistant? I am your employer. Besides, she’s smart. She studied at the Courtauld, Chelsea, Camberwell —’

‘How many art colleges does a person need?’

‘Well,’ she grinned slyly, ‘she was very good at getting

into

them.’

‘This isn’t helping.’

She laughed. ‘It will be an adventure!’

‘I don’t want an adventure.’

‘She’s different now.’

‘I work alone.’

‘Well —’ she rifled through the stacks of invoices and receipts, searching for something — ‘now you have an assistant to help you.’

‘This is nepotism, pure and simple!’

She looked up. ‘Nothing about Katie is pure or simple. The sooner you understand that, the easier it will be.’

‘What did she do in New York anyway?’

‘I’m not sure.’

‘I thought you two were close.’

‘Her father had just died. He was young; an alcoholic. She wanted a new start and we had some connections there; Paul knew one or two dealers who might be willing to help her find her feet. Tim Bolles, Derek Constantine —’

‘Constantine?’ Jack stopped. ‘I thought he only catered for the super-rich.’

‘Yes, well. He took a shine to her.’

‘I’ll bet he did!’

She gave him a look. ‘I don’t believe he’s that way inclined.’

‘I’m sure he inclines himself to whoever’s got the cash, which doesn’t exactly add to his charms.’

‘New York is not a city a young woman can just waltz into. You need contacts.’ Opening the top drawer, she sifted through its contents. ‘I’m just guessing, but I take it you don’t like him.’

‘My father had dealings with him. Years ago. So —’ he changed the subject — ‘she’s staying with you, is she?’

‘For the time being. Her mother lives in Spain.’ She sighed; her face tensed. ‘She’s so different. So entirely, completely different. I’d heard nothing for months … not even a phone call … and then out of blue, there she was.’

Suddenly a courier bike, buzzing like a giant wasp, tore past the doorway at breakneck speed.

‘Good God!’ Jack turned, tracking it as it narrowly avoided a couple of girls, coming out of a coffee shop. ‘They’re a menace! One of these days someone’s going to get hurt!’

‘Jack.’ Rachel pressed her hand over his and gave him her most winning smile. ‘Do this for me, please? I think it will be good for her; a trip to the country, time with someone closer to her own age.’

‘Ha!’ He squeezed her fingers lightly before moving his hand away. ‘I’m not a babysitter, Rachel. Where is this house anyway?’

‘On the coast in Devon. Endsleigh. Have you ever heard of it?’

He shook his head. ‘Look, I’m not… you know, good with people.’

‘Maybe. But you’re a good man.’

‘I’m an awkward man,’ he corrected, wandering over to the fireplace.