The Delaware Canal (5 page)

Read The Delaware Canal Online

Authors: Marie Murphy Duess

They started before dawn, moving from the dark of the early morning to the dark of the tunnels that brought them into the bowels of the earth. All of them were dressed in overalls and rubber boots and wore caps on their heads. And when the day was over, they left the mines to return home, as black as the coal they mined. Most of them were immigrants. They came from Ireland, Scotland, Italy, Hungary, Poland and Germany. Before 1842, there were no labor laws and no unions to protect them.

Miners and their families lived in what were called Patch Villages. These villages were laid out by class of mine workers, with the mine bosses and supervisors living at the head of the streets in larger, more comfortable houses. The miners' cabins weren't much more than matchstick houses, with two rooms, a kitchen area down and a garret upstairs where children slept. These cabins did little to keep out the rain and cold. The unskilled workers slept in worse conditions, in shacks sometimes filled with so many people that they had to sleep in shifts. And they paid a fairly high rent for this housing, which was taken out of their pay.

Although this book is about the Delaware Division Canal, it is important to touch on the story of the miners when talking about the transportation of the coal after it was dug out of the mountains. The narratives are intertwined, for without the first there would not have been the need for the latter; and possibly, without the brave men and little boys who descended sometimes more than a thousand feet deep into the ground with picks and shovels, the Industrial Revolution would not have been possible. It was best said by a coal miner in 1874:

[M]

illions of firesides of rich and poor must be supplied by our laborâ¦the magnificent steamer that ploughs the ocean, rivers and lakes, the locomotive, whose shrill whistle echoes and re-echoes from Maine to California, the rolling mills, the cotton mills, the flour mills, the world's entire machinery, is moved, propelled by our labor

.

25

The youngest of the miners were the “breaker boys”âchildren who worked in the building where coal was broken and sorted. They were as young as five years old, and according to Susan Campbell Bartoletti's book,

Growing Up in Coal County

, their hours at work were possibly the hardest and definitely the most heartbreaking.

The breaker boys sat in chutes below where cars filled with coal were tipped and the contents poured into a machine that pushed the coal down toward the boys. As the coal tumbled down the chutes, a blanket of black coal dust covered the children. They wore handkerchiefs over their mouths to try to keep from breathing in the dust and chewed tobacco to keep their mouths moist. (Again, these are children as young as five years old!) They worked from seven in the morning until six or six-thirty at night with very few breaks, separating slate and rock from the coal, hunched over their work all day without backrests to give them support. They weren't permitted to wear gloves because it interfered with their sense of touch and their fingers swelled and bled until they hardened with calluses.

The breaker bosses oversaw the little boys' work, usually with a club or broomstick against their backs if they slacked off or missed pieces of slate or rock. Sometimes, if the children resisted and protested because of the abuse, they were literally whipped back to work.

The work at the breakers was no less dangerous than the work going on below ground. Children's fingers were amputated in the conveyors; others fell down the chutes and became buried in coal or fell into the crusher where the coal was being ground along with their little bodies.

In John Spargo's exposé,

The Bitter Cry of the Children

, he describes the atmosphere of the breaker:

Within the breaker there was blackness, clouds of deadly dust enfolded everything, the harsh, grinding roar of the machinery and the ceaseless rushing of coal through the chutes filled the earsâ¦I was covered from head to foot with coal dust, and for many hours afterwards I was expectorating some of the small particles of anthracite I had swallowed

.

26

Boys as young as five years old worked in the breakers, one of the most hazardous jobs in the mines.

Courtesy of Robin G. Lightly, Mineral Resources program manager, Bureau of Mining and Reclamation, PA Department of Environmental Protection

.

As they got older they were “promoted” to work inside the mines, in the damp, cold, dark and rat-infested underground chambers. But that was okayâthey longed for the day. Bartoletti quotes a miner named Joseph Miliauskas, who reflected on what it was like to work as a breaker boy: “When I got down into the mines, that was paradise.”

27

“Nippers” were the youngest, around eleven years of age, and they tended the heavy wooden doors in the gangways. They were usually the first to hear the creaks and groans that would alert them to the danger of collapse, and it was their responsibility to warn the others.

“Spraggers” controlled the speed of the mine cars as they rolled down the slopeâagain one of the most dangerous jobs in the mines since they could be run over by the fast-moving cars when they reached down to apply the breaks. These boys lost arms, legs and their lives.

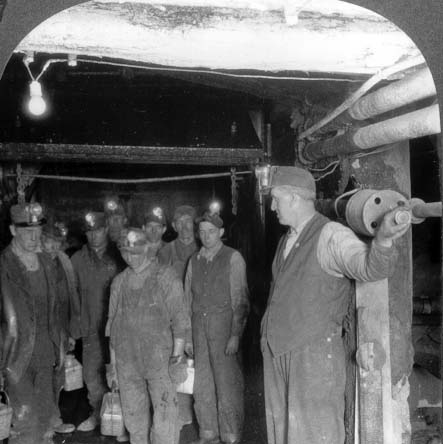

Miners descended into the dark, dank mines before dawn each morning.

Courtesy of Robin G. Lightly, Mineral Resources program manager, Bureau of Mining and Reclamation, PA Department of Environmental Protection

.

The mule drivers collected the coal in cars pulled by mules, and they could work as many as a six-mule team in the narrow passages of the mines. Although it wasn't the most pleasant job, it did afford them the opportunity to move about the mines from cavern to cavern, and it was one of the most sought-after jobs among the younger miners. Their responsibility was to get their cars full by quitting time, and if the work wasn't done, they stayed until it was. Miners were paid by the weight of the cars they filled, so it was important for the spraggers and the mule drivers to make certain that no coal was spilled or lost from the cars.

If they did the job right, they were promoted again and labored beside their fathers, brothers and uncles, working on the face of the walls of the mountains. They shared the same risk as the men, sometimes standing for hours in dank air with water up to their ankles, knowing that at any moment the roof could collapse or poisonous gas could escape. At the end of the day, they were brought back to the surface of the earth, exhausted and covered in black coal dust that was embedded in their skin.

Coal dust would embed itself into the skin of the miners, sometimes permanently.

Courtesy

Istockphotos.com

.

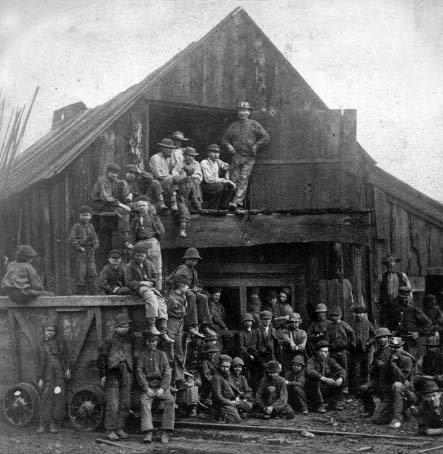

It was the backbreaking work of men and little boys in the mines that helped to fuel the Industrial Revolution.

Courtesy of Robin G. Lightly, Mineral Resources program manager, Bureau of Mining and Reclamation, PA Department of Environmental Protection

.

According to

The Death of a Great Company

by W. Julian Parton, the accident and death rate at the LC&N was consistently below the industry as a whole. “Management carried out excellent safety programs and did everything possible to train miners to work safely.” Yet mining was extremely dangerous, even under the best of conditions, and miners who were not injured or killed on the job often developed black lung disease.

It is not unfair to say that the Pennsylvania miners of the eighteenth century are among the true heroes of the Industrial Revolution.

The Molly Maguires

Working conditions in the early years of the anthracite mines were indisputably hard and often brutal. Whenever men work under cruel conditions for long enough, rebellion follows. Sometimes revolt comes in the form of union activities, sometimes in criminal activityâoftentimes, both, and from both sides of the argument.

In the 1700s and early 1800s, the miners were primarily Irish immigrants. Back in Ireland, in response to what the Irish farmers believed were unfair practices by landlords, a clandestine organization called the Molly Maguires was formed to correct transgressions. How the organization got its name has always been more folk tale than factual. One story is that “Molly” was a widow who had been evicted from her house and inspired defenders; another is that Molly was a young woman who led men on nighttime raids; and still another was that Molly owned a tavern where the secret society met. Some say that the name came about because the men in the secret society disguised themselves as women when on their raids.

Philadelphians will find it interesting that in this last assumption, the Molly Maguires took on a form of the Irish practice of “mummery.” (During festivals, men would blacken their faces, wear women's clothing and walk door-to-door demanding food, money or drink as payment for a performance.)

28

In the coal region of Pennsylvania, a society of miners organized themselves in the same manner to intimidate the coal mine owners and bosses who they believed were abusing them and their sons in the mines. They tried to unionize legally and called strikes, but failed. They believed that seeking to present their grievances through the courts was a waste of time since judges, lawyers and policemenâwho were mostly Welsh, German and Englishâdeliberately caused delays and injustices because of their strong anti-Irish, anti-Catholic sentiments. As the miners became more frustrated, the Mollys' activities became more violent, and the coal mine owners answered the violence in like manner.

One Pinkerton agent, an Irish immigrant named James McParlan, went undercover in the Molly Maguires to spy on them. Based on his reports, and for the most part solely on his hearsay and testimony, twenty men were arrested and ten sent to the gallows.

There isn't much written about the Molly Maguires' activities in Mauch Chunk, except that four men were convicted and hanged there in June 1877. They were convicted of killing two mine bosses. A Carbon County judge, Judge John P. Lavelle, later described the trial in this way:

The Molly Maguire trials were a surrender of state sovereignty. A private corporation initiated the investigation through a private detective agency. A private police force arrested the alleged defenders, and private attorneys for the coal companies prosecuted them. The state provided only the courtroom and the gallows

.

29