The Devil's Pleasure Palace (22 page)

Read The Devil's Pleasure Palace Online

Authors: Michael Walsh

What Critical Theory and political correctness seek to do is remove the music from our lives, to strip it, Soviet-style, of all secondary meaning, of all its layers, its poetry and (surprisingly, for this is one of the Unholy Left's favorite words) nuance. Nothing means more than what we can take at face value, except empirical evidence, which must be subjected to ceaseless analysis in an attempt to change plain meaning into something unknowable. For the Left, music functions didactically, its capacity to incite and inspire channeled into the service of the state, not the human heart. Thankfully, a losing proposition.

The Left's pleasure palaces are all around us, in their promised utopias of social justice, egalitarianism, sexual liberation, reflexive distrust of authority, and general nihilism. What they've brought about insteadâas all pleasure palaces mustâis death, destruction, and despair.

In 1966, Michelangelo Antonioni dropped a bombshell of a motion picture called “Blow-Up” upon an unsuspecting public. The Production Code was in hasty retreat, and

Blow-Up

titillated American audiences with its nude models writhing on purple paper with an anomic photographer played by David Hemmings. It was at once a documentary of Swinging London, a product of the Italian cinema at the top of its form, and an examination of the unknowability of knowledge. Coming just three years after the Kennedy assassination, it also played on the country's darkest obsessionsâis that Black Dog Man I see in the grainy blow-ups of the grassy knoll? But most of all, it expressed precisely what was about to drive the United States of America crazy: self-doubt.

It is fitting that the screenplay was based on a short story, “Las babas del Diablo” (“The Droolings of the Devil”), for it opened the door to the daemonic that would soon flood into American movie theatersâmost prominently, the quintessential alienation of Walter Penn's

Bonnie and Clyde

(1967) and Polanski's psycho-sexual horror show

Rosemary's Baby

(1968), which made Satan one of the protagonists and the father of the eponymous baby.

The nudity in

Blow-Up

of Jane Birkin and Gillian Hills attracted a good deal of critical and prurient attention, as did a brief topless scene by Vanessa Redgrave, but the central appeal of the movie lay in Hemmings's mesmerizing performance (fittingly, in later life, he became a magician) as Thomas, the seen-it-all fashion photographer whose pointless life, illustrated by his even more pointless sex life, suddenly comes into focus when, on a whim, he snaps some shots of Redgrave and a mysterious man in Greenwich's Maryon Park. Grainy blow-ups later reveal what might be a man with a gun. Upon a return to the park, he finds a dead body but has forgotten his camera. In a timely snapshot of the zeitgeist, Thomas stops in at a nightclub where Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, and the Yardbirds are playing; infuriated by a problem with his amp, Beck smashes his guitar on stage (Ã la The Who's Pete Townshend at the time), then tosses the broken guitar neck into the crowd, where Thomas scuffles for it. Out on the sidewalk, Thomas throws it away: pointless.

The daemonic, the diabolical, even a touch of “Listzomania” (the title of an over-the-top 1975 film by Ken Russell, starring The Who's lead singer, Roger Daltrey, in the title role)â

Blow-Up

had it all. But it was the haunting pantomime tennis game at the end, spontaneously played by a passing group of mimes in an open Jeep, that summed up the then-fashionable nihilistic futility of Thomas's search for the truth. When even the dead body that he thought he'd found disappears, Thomas is reduced to retrieving an imaginary tennis ball and tossing it back onto the court as everything but the grass vanishes.

Judged politically,

Blow-Up

might seem a dated piece of postwar cultural ennui. What is truth? What does it matter? Let's get laid! But that's not the way it plays. Hemmings's dispassionate photographer comes fully to life only in the presence of Death, when, in developing his pictures, he realizes that he may inadvertently have witnessed and recorded a crime, set up by Redgrave's femme fatale. The actress's haunting, aristocratic beauty was never better used, and her moment of attempted seductionâsex in exchange for the possibly incriminating photographsâremains in the mind long after other films of the period have faded. In the final scene, Hemmings casts off the bands of illusionsâwhat he took for reality was really just a series of futile gestures, like screwing the young models or

callously discarding Beck's broken guitar neck after fighting furiously for it. Only whenâtransformed by a womanâhe accepts the reality of the pantomime tennis game does he finally become a recognizable human being; in short, redeemed.

In the end, all art conforms to the same principles, whether it is created by the Left or the Right. Nearly every Disney movie ever made tracks the hero's journey Joseph Campbell laid out, even when the hero is a heroine. The most “conservative” movie ever made is probably

High Noon

(1952), which was written by a blacklisted Communist, Carl Foreman, from a partial draft by another blacklistee, Ben Maddow. While some see a subtextual evocation of McCarthyism, the text is the story of brave marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper) who, abandoned by the wimpy townsfolk of Hadleyville and even for a time by his pacifist Quaker wife, is forced to stand alone and face the vengeful badbellies arriving on the noon train. In the end, he's saved by his new bride, played by Grace Kelly, who shoots one of the criminals herself and tackles the head bad guy to provide her husband a clear shot at the man who has vowed to kill him.

Hollywood “formula” storytelling is often derided by those with no experience in filmmaking, or with little understanding of just what exactly that “formula” entails. But the ur-Narrative dwells deep within us, from Finn MacCool to Roland to Will Kane, and its stories are always the sameâeven when, on the surface, they aren't. Art has its own tricks to play on the Devil.

Illustration to Goethe's “Erlkönig,” Moritz von Schwind, 1917. A dying child and a desperate father fleeing seductive Death.

Satan Cast Out of the Hill of Heaven

, Gustave Doré, 1866. The Paradise that has been irrevocably lost is not ours but Satan's. No wonder those who advocate the satanic position fight for it so fiercely.

Mephistopheles in Flight,

Eugène Delacroix, 1828. The fallen angel, his wings still intact, flying impudently naked above the symbols of the Principal Enemy.

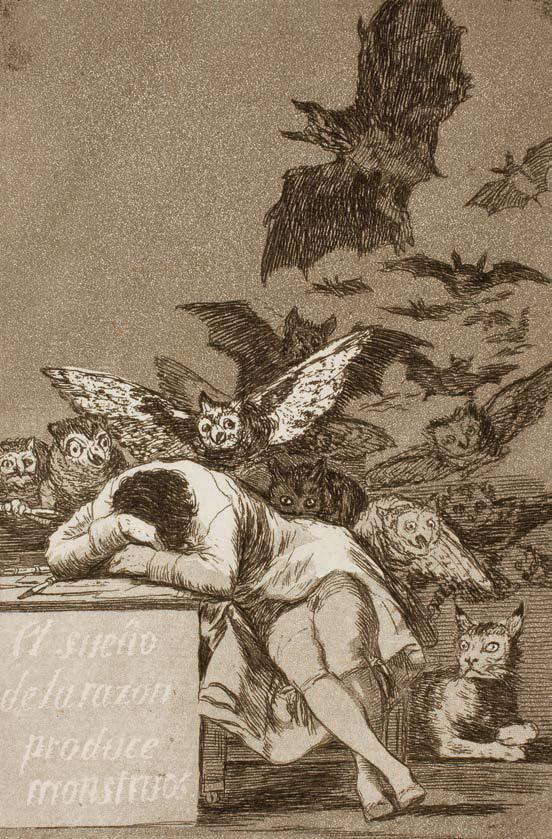

Fantasy abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: United with her, she is the mother of the arts and the origin of their marvels,

Francisco Goya, 1799.

The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in Sun,

William Blake, 1805. It is not for Christ to defeat Satan. Instead, that task is given to a woman, the Woman: Mary, the Mother of Christ.

Gretchen im Kerker (Gretchen in Prison),

Peter Cornelius, 1815. Sie ist gerichtet! (She is damned!)

Ist gerettet!

(Is saved!)