The Doctor Wore Petticoats: Women Physicians of the Old West (8 page)

Read The Doctor Wore Petticoats: Women Physicians of the Old West Online

Authors: Chris Enss

BOOK: The Doctor Wore Petticoats: Women Physicians of the Old West

5.7Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

As Nellie contemplated her decision, her thoughts settled on her grandmother’s struggle with typhoid fever and her mother’s fatal attempt to ease the physical pain she suffered. It didn’t take Nellie long to come to the conclusion that her “calling” was in medicine.

Just prior to Nellie graduating from the Inyo Academy, her father remarried. Nellie’s initial reaction to her stepmother was one of indifference, but as she got to know her she had a change of heart. She was an extremely kind woman and never failed to show Nellie love and compassion. She encouraged her stepdaughter in her future endeavors and cried for days when Nellie moved to San Francisco to attend medical school.

Smith accompanied his only child to the Bay Area and on to Toland Hall Medical College. He paid her tuition, helped her find a place to live, wished her well, and returned to Bishop. Their parting was difficult. Nellie was grateful for the opportunity he was giving her and vowed to be home soon with a diploma in hand. Neither fully realized how difficult it would be to fulfill that promise.

The attitude of many of the Toland Hall professors and students toward women in medicine was vicious. Most felt a woman’s presence in the medical profession was a joke. Nellie was aware of the prevailing attitude and was determined to prove them wrong. She devoted herself to her studies, arriving at school at dawn to work in the lab. She kept late hours, poring over

Gray’s Anatomy

and memorizing the definitions of various medical terms.

Gray’s Anatomy

and memorizing the definitions of various medical terms.

The harder she worked, the more resentful her male classmates became. They exchanged vulgar jokes with one another whenever Nellie or one of the other two women attending the school was around, in hopes of breaking their spirits. Professors were cold and distant to the women, oftentimes refusing to answer their questions.

Doctor R. Beverly Cole, Toland Hall’s Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, delighted in insulting female students during his lectures. He maintained publicly that “female doctors were failures.” He told students, “It is a fact that there are six to eight ounces less brain matter in the female. Which shows how handicapped she is.”

Nellie quietly tolerated Doctor Cole’s remarks and allowed them only to spur her on toward her goal of acquiring a degree.

While in her third year of medical school, Nellie took an intern position at a children’s hospital. Many of the patients that allowed her to care for them were Chinese. She assisted in many minor operations and births, and she helped introduce modern medicines and cures.

Months before Nellie was to graduate, she was granted permission to assist in a major surgery. Two physicians were required to perform an emergency mastoid operation on a deathly ill dock-worker. Nellie was one of two interns on duty and the only woman. The male intern fainted at the sight of the first incision. Nellie was a bit uneasy as well, but assured the doctor she could do the job when he ordered her at his side. She recounted the event in an 1893 journal entry:

The surgeon talked as he worked. He described the blood supply, the nerve supply, the vessels that must be avoided, the paralysis that would follow if he invaded the sacred precinct of the facial nerve. Chip by chip he removed the bone cells, but the gruesome spectacle had been magically transformed into a thrilling adventure. I forgot that I had a stomach; forgot everything but the miracle that was being performed before my eyes, until the last stitches were placed, the last dressings applied.

Nellie eagerly looked forward to graduation day. In spite of the fact that her grades were good and her talent for medicine was evident, the male faculty and students remained unimpressed with her efforts. She was confident that when she and the two other female students accepted their diploma, the men would be forced to recognize that a woman’s place in the emerging profession was a definite.

Shortly after passing her final examination, Nellie was summoned to the dean’s office. The dean was a man who did not share Nellie’s vision of women in medicine and because of that, she feared he was going to keep her from graduating. The matter he wanted to discuss, however, was how she wanted her name to appear on her diploma. She told the dean that her christened name would be fine. The man was furious. “Nellie Mattie MacKnight?” he asked her, annoyed. “Nellie Mattie?” Nellie did not know how to respond. “How do women ever expect to get any place in medicine when they are labeled with pet names?” he added.

The dean persuaded Nellie to select a more suitable name. She searched her mind for names from which her name might have been derived. “I had an Aunt Helen . . . and there was Helen of Troy,” she thought aloud. “You may write Helen M. MacKnight,” she said, after a moment of contemplation. The dean informed her that he would make the necessary arrangements. Before she left his office, he added, “See that it is Helen M. MacKnight on your shingle too!”

Nellie graduated with honors from Toland Hall Medical School. Her father and stepmother were on hand to witness the momentous occasion. As her name was read and the parchment roll was placed in her hands, she thought of her mother and grandmother, and pledged to help cure the sick. Chances for women to serve the public in that capacity were limited, however. Widely circulated medical journals stating how “doubtful it was that women could accomplish any good in medicine” kept women doctors from being hired. They criticized women for wanting to “leave their position as a wife and mother,” and warned the public of the physical problems that would keep women from being professionals. An 1895

Pacific Medical Journal

article surmised:

Pacific Medical Journal

article surmised:

Obviously there are many vocations in life which women cannot follow; more than this there are many psychological phenomena connected with ovulation, menstruation and parturition which preclude service in various directions. One of those directions is medicine.

In San Francisco in 1893, there was only one hospital where women physicians practiced medicine. The Pacific Dispensary for Women and Children was founded by three female doctors in 1875. The facility was designed to provide internships for women graduates in medicine and training for women in nursing and similar professions. Nellie joined the Pacific Dispensary staff, adding her name to the extensive list of women doctors already working there from all over the world.

In the beginning, Doctor MacKnight’s duties were to make patient rounds and keep up the medical charts by recording temperatures, pulses, and respiration. After a short time she went on to deal primarily with children suffering from tuberculosis. She also assisted in surgeries and obstetrics, and was involved in diphtheria research.

In 1895, Nellie left the hospital and returned home to help take care of her ill stepmother. Within a month after Nellie’s arrival, her stepmother was on her way to a full recovery. Nellie decided to stay on in Bishop and set up her own practice.

The response she received from the community and the two other male physicians in town was all too familiar to her. She persevered, however. She set up an office in the front room of her house, stocked a medicine cabinet with the necessary supplies, and proudly hung out a shingle that read HELEN M. MACKNIGHT, M.D.,

PHYSICIAN AND SURGEON.Doctor MacKnight traveled by cart to the homes of the handful of patients who sought her services. She stitched up knife wounds, dressed severe burns, and helped deliver babies. As news of her healing talents spread, her clientele increased. Soon she was summoned to mining camps around the area to treat typhoid patients. Although her diploma and shingle read Helen M. MacKnight, friends and neighbors who had known her for years called her “Doctor Nellie.” It became a name the whole countryside knew and trusted.

While tending to a patient in Silver Peak, Nevada, Nellie met a fellow doctor named Guy Doyle. The physicians conferred on a case involving a young expectant teenager. Doctor Doyle treated Doctor MacKnight with respect and kindness. Nellie was surprised by his behavior, and made note of her reaction in an 1898 journal entry:

I had worked so long, fighting my way against the criticism and scorn of the other physicians of the town, that it seemed a wonderful thing to find a man who believed in me and was willing to work with me to the common end of the greatest good to the patient.

What began as a professional relationship grew quickly into romance. The couple decided to pool their resources and go into business together. They opened an office inside a drugstore on the main street of Bishop. In June of 1898, Helen and Guy exchanged vows in a ceremony that was attended by a select few in Inyo County. According to Nellie’s account of the event:

My wedding dress was a crisp, white organdy, with a ruffled, gored skirt that touched the floor all the way around. The waist had a high collar and long sleeves. The wedding bouquet was a bunch of fragrant jasmine. . . . A small group of friends came to witness the ceremony, and the gold band that plighted our troth was slipped over my finger.

Doctor Nellie MacKnight Doyle and Doctor Guy Doyle provided the county with quality medical care for more than twenty years. The couple grew their practice and took care of generations of Bishop residents. Nellie and Guy had two children—a girl and a boy. The daughter followed in her mother’s footsteps and pursued a medical degree. Upon her graduation from college, she was given a foreign fellowship in bacteriology.

Doctor Nellie M. MacKnight spent the last thirty years of her life studying and practicing anesthesiology. She died in San Francisco in 1957 at the age of eighty-four.

PATTY BARTLETT SESSIONS

A doctor, if he had good sense would not wish to visit women in

childbirth. And if a woman had good sense she would not wish a

man to doctor them on such an occasion.

—Brigham Young, December 1851

The shrill cry of a woman in immense pain filled the otherwise quiet night sky over Utah’s Salt Lake Valley. Patty Bartlett Sessions smiled down at the expectant mother and wiped the sweat off her forehead. Barely out of her teens, the woman was in the final stages of delivery and frightened of the experience her body was going through. Her pleading eyes found compassion in the fifty-two-year-old midwife caring for her.

Patty Bartlett Sessions had helped bring hundreds of babies into the world. The sparsely populated western frontier of the 1800s was in need of trained birth attendants who could help ensure mother and child survived the grueling process of labor and delivery. The gifted midwife calmly reassured the frantic mother-to-be with stories of the healthy infants she had laid in the arms of anxious mothers. The exhausted woman nodded and tried to smile through a contraction.

Patty did not solely rely on practical experience to help her with her job. She studied the pages of a medical book entitled

Aristotle’s Wisdom: Directions for Midwives.

The publication contained advice and counsel for delivering a baby, along with more than 300 photographs of fetuses in various stages of development. She had pored over numerous books on the subject, and in 1847 was one of the most trusted women in the midwife profession.

Aristotle’s Wisdom: Directions for Midwives.

The publication contained advice and counsel for delivering a baby, along with more than 300 photographs of fetuses in various stages of development. She had pored over numerous books on the subject, and in 1847 was one of the most trusted women in the midwife profession.

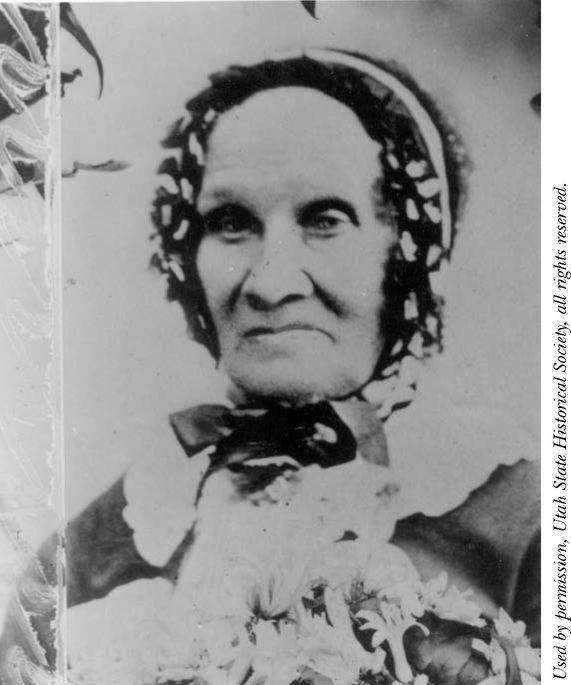

ONE TIME HELPING TO DELIVER A CHILD LED PATTY BARTLETT SESSIONS TO PURSUE A MEDICAL PROFESSION.

Other books

Dreaming of Amelia by Jaclyn Moriarty

Joan Hess - Arly Hanks 10 by The Maggody Militia

A Woman To Blame by Connell, Susan

Valkwitch (The Valkwitch Saga Book 1) by Michael Watson

Hosker, G [Sword of Cartimandua 04] Roman Retreat by Griff Hosker

Out of My Depth by Barr, Emily

The Oath by Jeffrey Toobin

The Right Word in the Right Place at the Right Time by William Safire

Single Ladies 7 & 8: " That's What Friends Are For" by Blake Karrington

Laughing Man by Wright, T.M.