The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini and other Strange Stories (7 page)

Read The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini and other Strange Stories Online

Authors: Reggie Oliver

Suddenly he was flung down on the ground. It was not very hard, but yielding, almost soft and composed of huge flakes of something. Above him the sparks still swirled and twittered in the cosmic winds while at his feet he was conscious of a faint grey light like the beginning of dawn.

The flakes on which he had fallen seemed to be sheets of paper and he could walk across them with some difficulty. As he looked about him, his world began to take shape. The faint grey light seemed to originate from one source towards which Jason began to walk.

It was a long walk, that was all Jason could say afterwards, because time in this universe had lost its precise meaning. As he experienced it, it could have been months, years or centuries, and in that time he exhausted every thought and memory that he possessed. He wondered if, like those legendary enraptured monks, or the seven sleepers of Ephesus, he would emerge into his world again years after he had left it with everyone thinking he was dead.

Slowly, slowly the light grew until he could see what he was walking on. They were pieces of paper, thousands, millions of them stretching out to the dim horizon in all directions. Picking one up he saw that it had been drawn on, an exquisite little sketch of a rock and two silver birches, their branches intertwined, their leaves blowing slightly in the wind. He held onto it and picked up another. Here was a drawing in sanguine of a valley at evening with a classical temple and some shepherds feeding their flocks, another beautiful thing. He picked up another piece of paper and another, each one of which had a drawing on it of extraordinary excellence. All the drawings showed either fragments of nature, or classical scenes and figures. Jason could have spent hours, years with them, but he felt the need to press on towards the light. He dropped the other drawings, and kept the one he had picked up of the rock and the silver birches, remembering that in some other life Anthony Blunt, scholar and traitor, had called Gaspard Dughet ‘the Silver Birch Master’.

On, on towards the light, and in the light Jason saw a seated figure, the original of the seated figure he had seen at the end of the frieze in the temple. As he sat the figure drew on a piece of paper and when he had finished it to his satisfaction he let it fall and then picked up another piece of paper to draw on. He never stopped; he seemed compelled to draw and draw until time itself had an end. When Jason had come close to him he at last looked up.

Jason wanted to speak but could not. His eyes met those of the Silver Birch Master—Jason was sure it was him—and rested for a long time in them. The man’s eyes were infinitely tired and Jason felt a wave of pity for him so strong it seemed to be both inside and outside him at the same time. It blew like the wind and as his compassion raged, the million drawings which carpeted the landscape were swept upwards into the surrounding air like a blizzard. Thunder rumbled in the distance.

As Jason’s passion subsided, so did the turbulence. The drawings fell to the ground and the air became brighter. The Old Master whom Jason knew to be Dughet rose up from his seat. There seemed to be a new gleam of purpose in his eye. He pointed to his right and there through the white mist Jason could see the scene which he had originally entered, the picture

In Arcadia.

Then the Master pointed to his left and there, dim, very distant, Jason could see the living room of his absurd little Fulham flat.

The Master seemed to be offering him a choice: to go back into the glow of Arcadia, or to return to his flat, flat in more than one sense of the word. Jason did not hesitate, however; he turned right towards Fulham. Once he looked back and saw that the Master had left his seat. Where he had gone he did not see.

Many years later it seemed to Jason that he was awake once again in his own London room, seated in front of the painting, and the clock had only ticked on half an hour or so. He would have believed that he had experienced little more than a peculiarly vivid dream. That was what he urgently wanted to believe, but he was prevented from doing so by the fact that he found he was still holding a piece of paper on which was an exquisite drawing of a rock and some silver birches.

He decided at that moment that he must return

In Arcadia

to its rightful owner as soon as possible.

**

The only question was how. Eventually he took the simplest, most cowardly course. He wrapped the picture up, wearing gloves the whole time, and sent the parcel off to Sir Ralph Gauge at Charnley Abbey from a busy post office in North London, far from his Fulham flat. He even put on a light disguise to do so. Together with the picture he had included a note written in capitals on a blank sheet of paper.

‘I found this at the Abbey and am returning it to you. It is a fine example of the work of Gaspard Dughet—sometimes known as Gaspard Poussin—1615-1675.’

On receiving his picture back, Sir Ralph immediately put it up for sale at Christie’s where it fetched a handsome price, as it recommended itself to potential buyers both by its artistic merit and by the publicity which it had attracted. A good deal was made of its mysterious discovery and return in the newspapers. THIEF WITH A CONSCIENCE read one of the headlines, though some more cynical commentators thought that the thief was returning the picture because he couldn’t sell it. Suspicion fell briefly on the academic who had been filmed at Charnley Abbey talking about Walpole, but no action was taken as no crime had been reported at the time. Jason was neither mentioned, nor interviewed by the press, as he was an unknown actor and obviously ignorant of everything except acting.

With the money he got from the picture Sir Ralph bought a steeplechaser which broke a leg in the Grand National and had to be destroyed. But Jason’s career flourished after a fashion

.

The small success of his Horace Walpole convinced the casting directors (an unimaginative breed) that he was an expert at eighteenth century roles. Consequently, the following year found him playing Sir Joshua Reynolds in a Channel 4 film about his alleged rivalry with Gainsborough.

While researching for the role Jason read Reynolds’

Discourses to the Royal Academy

. In the famous ‘Sixteenth Discourse’ he came across the following passage written in Reynolds’s typically lumbering, Johnsonian prose:

. . . or like the celebrated Roman artist Gaspard Poussin, who believed, not solely that his fame would be immortalised in his work, but that he himself, soul and body, might mysteriously live for ever in it. He assured himself that, by means of certain occult operations, his spirit might enter one of his own sylvan idylls, and there dwell through all eternity, pleasantly enjoying the fruits of his artful imagination. It is credulously believed by some that he achieved this, for the death of this Master was indeed attended by no little mystery, and there is said to be a work in which he eternally resides, though no man has determined which. I am obliged to that learned virtuoso, my friend Sir Augustus Gauge Bt., for this curious legend.

EVIL EYE

A week after he had returned from the States Alex invited me out for a drink at Freek’s, the wine bar nearest our office. Alex was a high flyer and one of the youngest art directors in DH Associates; I was just a humble copywriter, but we got on, sort of. I don’t mind being patronised.

When we got to Freek’s Alex ordered a bottle of Bollinger. It was not that unusual: Alex tended to go over the top. Work hard, play hard, he used to say and it showed. Not that he was bad looking; according to some of the girls in the office he was definitely fanciable. He was dark—very shiny gelled black hair—and dressed sharp in dark suits. Big brown eyes with long lashes which the girls liked; but he was a bit podgy. He was pale and puffy and sweated a lot. On the other hand he was smart, no question, and everyone predicted a brilliant future.

I could tell at once he was worked up, bursting to confide in someone, and I suppose I was the nearest available dumping ground. For a few minutes we talked about the States where he’d been for six months working with DH’s parent company, learning management strategies, new marketing techniques, all that stuff. I could see he was just delaying the inevitable. At last he revealed what was on his mind:

‘You remember that video surveillance system we did a campaign for last year?’

‘

Hidden Eye

?’

‘That’s the one.’ I remembered it well. As copywriter, I had come up with literally hundreds of different lines for them, all to do with eyes, though ears came into it as well. I won’t embarrass you with the results. Hidden Eye was the very latest in home security. It was a state-of-the-art ‘intelligent’ surveillance system which could be programmed just like an alarm. Movement, light or noise acting as the trigger, as soon as something in the room changed, it would start recording. It would only stop when the thing that had made it start, stopped and then after half an hour of immobility. The sound system had the intelligent capacity for editing out background and traffic noise and concentrating on the human voice. The pictures it produced were of high quality, even in dim light, and it had a number of Unique Selling Points. One was that the images were immediately transmitted to a computer, thus providing an almost infinite and totally silent storage capacity, since there was no need to keep switching over DVDs or videotapes. Another USP was that the whole system had its own back-up power reserve in the event of a power cut. Once it had picked up the moving object it would track it round the room maintaining focus on it and picking up its sound with directional microphones. Above all, it was so miniaturised that the camera—just a tiny lens on the end of a fibre optic cable—could be easily hidden. When you wanted to access the recordings, you simply did so by watching them on your personal computer. Alternatively you could make your own discs and watch them through a DVD player.

‘Well,’ said Alex, ‘they liked the ads so much I managed to wangle a freebie out of them. I got them to set one of their systems up in my flat. Said I wanted to test drive it, that sort of crap.’

‘Whereabouts in your flat?’

‘Guess.’

‘Bedroom?’

‘Got it in one.’ Alex smiled, then wiped the sweat off his face with a handkerchief. He looked at me almost nervously, as if he was unsure how I would react. I was unsure how I should react. ‘Then came the call to America. Quite unexpected. Apparently several people in the office were up for it, but I got it. So I was going to be away for six months and I thought I’d let the flat out. So I did.’

‘Who to?’

‘This girl called Carol. I saw quite a few before I decided on her. Twenties, blonde, gorgeous legs, nice pair of tits. Nice face. She was just a temp somewhere, but she had this lah-di-dah accent. Very Cheltenham Ladies. She sort of took my fancy. I dropped the rent quite a bit for her.’

‘You don’t mean—’

‘That’s right,’ said Alex looking away and pouring himself another glass, ‘I left the Hidden Eye on.’

‘Did you tell her about it?’

‘Good God no!’ Alex managed to dig up some moral indignation from somewhere. ‘No. I mean, I don’t want you to think that this was just some sort of sleazy voyeurist trip for me. No. It was more like research. A unique insight into another life.’

‘If she ever finds out . . .’

‘She won’t. I haven’t seen her since I came back. She’d left the place immaculate, rent paid, bills paid, everything. I wish I could always have a tenant like her. I’m glad now I lowered the rent for her.’

‘You lowered the rent because she had nice tits.’

‘Yes. Well . . . I mean, I really wanted to find out. What do they do when no-one is looking; or rather, when they think no-one is looking? I could really get inside the psyche of this person. Could be useful for business. The insights you get. You know the Heisenberg principle: the presence of an observer alters the course of an experiment? That may be true in physics, but in human experiments it only counts if the humans involved know they’re being observed. Don’t you see? This is the real thing. All these fly on the wall docu-soaps are rubbish compared to this.’

‘Bollocks. You just wanted to see her tits.’

‘Do you have to be so crude? Anyway, aren’t you just a little bit curious to know what I found out?’

‘What did you find out?’

‘You’d be amazed. I haven’t looked at it all. Christ, there’s hours of the stuff, but you would be amazed.’

‘In what way?’

‘Come and see for yourself. Don’t tell me you wouldn’t walk over red hot coals to see it.’

‘Well . . .’

‘We could analyse it together. What d’you say? Friday evening after work. We’ll pick up a take-away and make a night of it.’

I wish I’d said no. Jesus, Christ, God! I wish I’d said no.

**

Alex’s flat was in a converted warehouse at Canary Wharf. It was one of those apartments that people like Alex chose to refer to as a ‘pad’, all black leather and chrome and sliding doors, with the clutter of everyday life kept firmly out of sight behind them.

The evening seemed potentially an enjoyable one. We had bought a lavish Chinese takeaway which we spread out on the low coffee table in front of the television and there were plenty of cold beers in the fridge. Our entertainment promised to be both titillating and psychologically fascinating. I wish I could say that I felt guiltier about the intrusion we were making into a private life. Now, it seems horrible that I could have consented to participate, but perhaps that is because of what happened. I did feel uneasy, which may not be very much to record in my favour, but I did. I asked Alex why he had chosen me to watch with him.

‘Because you’re an artist; you’re serious about writing,’ he said. The basis for this was that I had once told him that I was trying to write a novel. ‘You’ll understand. The others would either leer or disapprove.’ Of course I was flattered and this stifled my anxieties.

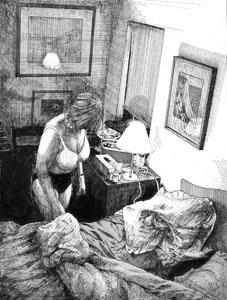

Alex had spent the intervening few days burning the recordings onto a disc for us to watch. For about an hour or so, we watched Carol getting up and going to bed and having long conversations with someone called ‘Tishy’ or ‘Tish’. It did not take me long to forget that I was invading a private world because it was not long before I felt myself part of it. Carol’s universe did not appear to be a very exciting one, but its very banality had a certain charm. There was the clumsy, uncoordinated little dance that she sometimes did in her underwear when she played a favourite CD. There was the wrapt absorption with which she examined her slender naked body in the mirror, wondering perhaps how desirable she was, little knowing that her vulnerability made her very desirable. There was the pert way in which she stuck her bottom out before farting and then flapped the smell away with a little wave of the hand. I suppose in someone older or less pretty all these things would have seemed grotesque, even pathetic.

She appeared to be a good girl, if not perhaps aggressively intelligent. She went home to her parents in Gloucestershire every weekend; her gossip on the phone to Tishy was giggling and unmalicious; if she brought men back to the flat they did not enter her bedroom in which she slept every night of the working week. I began to fantasise about meeting her, taking her out and, armed with my secret knowledge, seducing her. In the middle of this reverie Alex stopped the DVD player. ‘Well,’ he said. ‘That sort of thing goes on for several weeks and then there’s a change. This is where it gets really weird.’ He began to scan through the DVD while I contemplated going home. I did not want there to be a change. I wanted her to continue in the same sweet innocent ways, and I dreaded the prospect of something sleazier.

It began with her return one evening, drunk or stoned, and collapsing onto the bed in convulsive sobs. That night she did not undress to sleep. After that her life seemed to become more frantic: the room became messier, she was frequently drunk, she got up and went to bed at odd times. The talks with Tishy seemed the same as ever, but there were other calls more subdued and intense in which painful relationships were discussed and explored.

There was someone in particular called Kel whom she rang up from time to time. This Kel—one could not tell if it was male or female—seemed to act as a confidant. To Kel she would retail, with some reluctance at first, her secret feelings and fantasies. She was so ashamed of them and yet they were like the thoughts that come to all of us. She occasionally felt resentful of people she loved and who loved her. She was irritated by her parents when she ought to have been grateful. She had sexual fantasies of a mildly masochistic kind. She spoke to Kel with greater frequency and each time she did she was made to repeat the accounts of her fantasies, and, as she did so, the fantasies became gradually more extreme.

Then she began bringing men into her bedroom. They were joyless sexual encounters with men indiscriminately chosen. Sometimes there was brutality and she would cry out in pain, but she offered no resistance. I wanted to shout out and tell her to stop; either that or stop watching, but I could do neither. I looked over at Alex and he was transfixed. The phone calls to Kel continued. She told him about the men, always ending a graphic account with the pathetic words: ‘I think I’m beginning to learn.’

Then these one-night stands stopped abruptly. For a week or so a semblance of normality was restored. Alex said: ‘This is where I stopped watching.’ It was now three in the morning, but we were still wide awake. Alex turned the DVD player off and went to make some coffee.

‘We ought to know what happened to her,’ I said. ‘Okay,’ said Alex. ‘I sort of feel I shouldn’t go on, but you’re right. We have to see it through to the end now.’

Was I right? I wasn’t sure. We drank coffee in silence then Alex turned the DVD player on again. She was still seeing no men, but the phone calls were changing. She was talking less and listening more. Sometimes the phone would ring and you knew it was Kel just from the solemn way she would reply:

‘Yes . . . yes . . . yes . . . yes . . .’

Then one evening the bedroom door opened and Carol walked in, turned and said: ‘Come in, Kel.’ A man entered. He was well built, of medium height, and in his fifties, perhaps older. He was bald except for a light frizz of white hair around his cranium. The features were strong, a short straight nose, a firm chin and a small thin-lipped mouth. He had an aura of purpose and power, and he had obviously kept himself in shape. There was something undeniably magnetic about him, but also repulsive. Wherever he looked he looked with unblinking intensity.

Alex almost shouted: ‘Christ, she’s not going to bed with him!’

‘Some girls like older men.’

‘But my God, him!’

‘Perhaps she’s not going to bed with him,’ I said, not believing but hoping. ‘He could be just a sort of father figure, or something.’

Carol did not seem to be afraid of Kel so much as utterly submissive. He told her to take off her clothes, which she did mechanically, without any eagerness, keeping her eyes on him. He, meanwhile, was looking at her raptly with that intense, impersonal stare of his.

When she had finished she stood ankle-deep in discarded clothes. Kel stepped onto them and reached out with his left hand to touch one of her breasts. Just before he touched them, his shoulders suddenly raised themselves and he became rigidly still. For a few moments he remained like this while Carol continued to gaze at him, bewildered.

Suddenly he turned his head to stare directly at the camera. Alex and I both jumped. He might have been in the room, the look was so immediate and intense. It seemed to leap at us across the barriers of technology and time. His extraordinary pale blue eyes were filled with concentrated loathing. Like everything about him, there was something purposeful in his look. It was not rage, or hatred merely for the sake of rage, it was the performance of some indefinable act.

‘My God, he’s seen us!’ said Alex involuntarily.

‘Turn it off,’ I said.

‘No! No! This is ridiculous. He can’t do anything. We must see what happens.’

The man was still staring directly into the lens, but now he was mouthing something. We listened intently but could hear no words. Then the screen snowed over. Wild colours flashed across it so vivid that they hurt our eyes: acid greens, electric blues, fire reds. Then the screen cleared and we were in the bedroom again. It was a clear picture except that from time to time the whole image quivered in a strange way, as if the camera were looking upwards through the troubled surface of a pool of water.