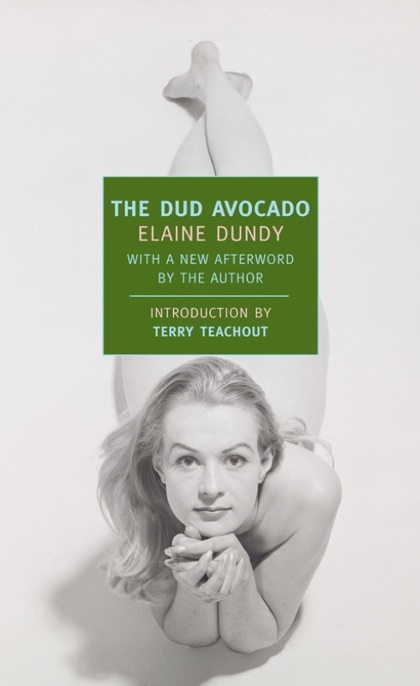

The Dud Avocado

Authors: Elaine Dundy

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

CLASSICS

ELAINE DUNDY

was born in New York City, has lived in Paris and London, and was married for a time to theater critic Kenneth Tynan. She has written plays, novels, and biographies, including

Elvis and Gladys

. Her work has appeared in

The New York Times, Esquire

, and

Vogue

among other publications. A resident of Los Angeles, her most recent book is her autobiography,

Life Itself!

TERRY TEACHOUT

is the drama critic of

The Wall Street Journal

and the music critic of

Commentary

. His books include

The Skeptic: A Life of H. L. Mencken, All in the Dances: A Brief Life of George Balanchine

, and

A Terry Teachout Reader

. He writes about the arts at www.terryteachout.com.

ELAINE DUNDY

Introduction by

TERRY TEACHOUT

It is the destiny of some good novels to be perpetually rediscovered, and Elaine Dundy’s

The Dud Avocado

, I fear, is one of them. Like William Maxwell’s

The Folded Leaf

or James Gould Cozzens’s

Guard of Honor

, it bobs to the surface every decade or so, at which time somebody writes an essay about how good it is and somebody else clamors for it to be returned to print, followed in short order by the usual slow retreat into the shadows. In a better-regulated society, of course, the authors of such books would be properly esteemed, and on rare occasions one of them does contrive to clamber into the pantheon—Dawn Powell, the doyenne of oft-rediscovered authors, finally made it into the Library of America in 2001—but in the normal course of things, such triumphs are as rare as an honest stump speech.

The Dud Avocado

is further handicapped by being funny. Americans like comedy but don’t trust it, a fact proved each year when the Oscars are handed out: our national motto seems to be Lord Byron’s “Let us have wine and women, mirth and laughter/Sermons and soda-water the day after.” To be sure,

The Dud Avocado

is perfectly serious, but it preaches no sermons, and what it has to say about life must be read between the punch lines. That was what kept Powell under wraps for so long—nobody thought that a writer so amusing could really be any good, especially if she was also a woman—and it has been working against Elaine Dundy ever

since she published

The Dud Avocado

, her first novel, in 1958. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that

The Dud Avocado

has never been out of print in England. I’m no Anglophile, but I readily admit that the Brits are better at this sort of thing. Unlike us, they treat their comic novelists right, perhaps because Shakespeare and Jane Austen taught them early on that (as Constant Lambert once observed apropos of the delicious music of Chabrier) “seriousness is not the same as solemnity.”

Now

The Dud Avocado

is out again in the United States, and I’ll bet money that some dewy-eyed young critic is going to read it for the first time and write an essay about how Sally Jay Gorce, Elaine Dundy’s adorably scatty heroine, was the spiritual grandmother of Bridget Jones. To which I say … nothing. I actually kind of like poor old Bridget, but if you want to properly place

The Dud Avocado

in the grand scheme of things, you should look not forward to Chick Lit but backward to

Daisy Miller

. Sally is Daisy debauched, an innocent ambassador from the New World who crosses the Atlantic, loses her virginity, and learns in the fullness of time that experience, while not all it’s cracked up to be, is nothing if not inevitable—and that Europe, for all its sophisticated ways, is no longer the keeper of the flame of Western civilization. Paris may be “the rich man’s plaything, the craftsman’s tool, the artist’s anguish, and the world’s largest champagne factory,” but you don’t have to live there to live, and once Sally gets to know some of its not-so-nice residents, she has a flash of full-fledged epiphany that is no less believable for having popped up in the middle of a comic novel:

“They are corrupt—corrupt,” I kept saying to myself, over and over again, as I paced around the room. It was the first time I’d ever used that word about people I actually knew, and again the idea that I could take a moral stand—or rather, that I couldn’t avoid taking one—filled me with the same confusion it had that morning.

I don’t want to leave the impression that

The Dud Avocado

is in any way po-faced. It is above all a book about youth, about a clever

girl’s realization that she is up to her ears in possibility, and every page bears the breathless stamp of her new-found freedom: “Frequently, walking down the streets in Paris alone, I’ve suddenly come upon myself in a store window grinning foolishly away at the thought that no one in the world knew where I was at just that moment.” In the very first sentence, Sally tells us that it is “a hot, peaceful, optimistic sort of day in September,” the kind of day that Ned Rorem, another clever young American who came to Paris in the Fifties, must surely have had in mind when he turned Robert Hillyer’s “Early in the Morning” into a perfect little song about what it feels like to find love on the rue François Premier: “I was twenty and a lover/And in Paradise to stay,/Very early in the morning/Of a lovely summer day.” If you read it without laughing, you have no sense of humor, but if you read it without shedding at least one tear, you have no memory.

The Dud Avocado

was extremely well received on its initial publication. “It made me laugh, scream, and guffaw (which, incidentally, is a great name for a law firm),” Groucho Marx declared in a fan letter to the author. “If this was actually your life, I don’t know how the hell you got through it.” It was, more or less, and Groucho didn’t know the half of it, for in 1951 Dundy had the bad luck to marry Kenneth Tynan, a great drama critic who turned out to be a comprehensively lousy husband, and though she would publish other good books, she never became quite as famous as she should have been. To make matters worse, Dundy began to lose her sight shortly after writing an alarmingly candid memoir cheerily titled

Life Itself!

in which she told her side of the unhappy story of her marriage. By then

The Dud Avocado

, her best book, had already gone through three or four cycles of obscurity and revival. Perhaps this long-overdue new edition will bring it the permanence it so richly deserves.

But even if

The Dud Avocado

is doomed to remain one of those novels that is loved by a few and unknown to everyone else, we lucky few who love it will never stop recommending it to our friends, for it is so full of charm and life and something not unlike wisdom that there will always be readers who open it up and see at

once that it is just their kind of book. Every time I read it, I find myself tripping over sentences I long to have written: “A rowdy bunch on the whole, they were most of them so violently individualistic as to be practically interchangeable.” “It’s amazing how right you can sometimes be about a person you don’t know; it’s only the people you do know who confuse you.” “I mean, the question actors most often get asked is how they can bear saying the same things over and over again night after night, but God knows the answer to

that

is, don’t we all

anyway

; might as well get paid for it.” I rank it alongside

Cakes and Ale

,

Scoop

,

Lucky Jim

, and Dawn Powell’s

A Time to Be Born

, a quartet of soufflé-light entertainments that will still be giving pleasure long after most of the Serious Novels of the twentieth century are dead, buried, and forgotten. A chick litterateuse could do a lot worse for herself.

—T

ERRY

T

EACHOUT

PART ONE

“I want you to meet Miss Gorce, she’s in the embalming game.”

—J

AMES

T

HURBER

(

Men, Women, and Dogs

)

I

T WAS A

hot, peaceful, optimistic sort of day in September. It was around eleven in the morning, I remember, and I was drifting down the boulevard St. Michel, thoughts rising in my head like little puffs of smoke, when suddenly a voice bellowed into my ear: “Sally Jay Gorce! What the hell? Well, for Christ’s sake, can this really be our own little Sally Jay Gorce?” I felt a hand ruffling my hair and I swung around, furious at being so rudely awakened.

Who should be standing there in front of me, in what I immediately spotted as the Left Bank uniform of the day, dark wool shirt and a pair of old Army suntans, but my old friend Larry Keevil. He was staring down at me with some alarm.

I said hello to him and added that he had frightened me, to cover any bad-tempered expression that might have been lingering on my face, but he just kept on staring dumbly at me.

“What

have

you been up to since … since … when the hell

was

it that I last saw you?” he asked finally.

Curiously enough I remembered exactly.

“It was just a week after I got here. The middle of June.”

He kept on looking at me, or rather he kept on looking over me in that surprised way, and then he shook his head and said, “Christ, Gorce, can it only be three short months?” Then he grinned. “You’ve really flung yourself into this, haven’t you?”

In a way it was exactly what I had been thinking, too, and

I was on the point of saying, “Into what?” Very innocently, you know, so that he could tell me how different I was, how much I’d changed and so forth, but all at once something stopped me. I knew I would have died rather than hear his reply.

So instead I said, “Ah well, don’t we all?” which was my stock phrase when I couldn’t think of anything else to say. There was a pause and then he asked me how I was and I said fine how was

he

, and he said fine, and I asked him what he was doing, and he said it would take too long to tell.

It was then we both noticed we were standing right across the street from the Café Dupont, the one near the Sorbonne.

“Shall we have a quick drink?” I heard him ask, needlessly, for I was already halfway across the street in that direction.

The café was very crowded and the only place we could find was on the very edge of the pavement. We just managed to squeeze under the shade of the awning. A waiter came and took our order. Larry leaned back into the hum and buzz and brouhaha and smiled lazily. Suddenly, without quite knowing why, I found I was very glad to have run into him. And this was odd, because two Americans re-encountering each other after a certain time in a foreign land are supposed to clamber up their nearest lampposts and wait tremblingly for it all to blow over. Especially me. I’d made a vow when I got over here never to

speak

to anyone I’d ever known before. Yet here we were, two Americans who hadn’t really seen each other for years; here was someone from “home” who knew me

when

, if you like, and, instead of shambling back into the bushes like a startled rhino, I was absolutely thrilled at the whole idea.

“I like it here, don’t you?” said Larry, indicating the café with a turn of his head.

I had to admit I’d never been there before.

He smiled quizzically. “You should come more often,” he said. “It’s practically the only nontourist trap to survive on the Left Bank. It’s

real

” he added.

Real, I thought … whatever that meant. I looked at the Sorbonne students surging around us, the tables fairly rocking under their pounding fists and thumping elbows. The whole vast panoramic carpet seemed to be woven out of old boots, checkered

wool and wild, fuzzy hair. I don’t suppose there is anything on earth to compare with a French student café in the late morning. You couldn’t possibly reproduce the same numbers, noise, and intensity anywhere else without producing a riot as well. It really was the most colorful café I’d ever been in. As a matter of fact, the most

colored

too; there was an especially large number of Singhalese, Arab and African students, along with those from every other country.

I suppose Larry’s “reality” in this case was based on the café’s internationality. But perhaps all cafés near a leading university have that authentic international atmosphere. At the table closest to us sat an ordinary-looking young girl with lank yellow hair and a gray-haired bespectacled middle-aged man. They had been conversing fiercely but quietly for some time now in a language I was not even able to

identify

.

All at once I knew that I liked this place, too.

Jammed in on all sides, with the goodish Tower of Babel working itself up to a frenzy around me, I felt safe and anonymous and, most of all, thankful we were going to be spared those devastating and shattering revelations one was always being treated to at the more English-speaking cafés like the Flore.