The Eastern Front 1914-1917 (31 page)

Read The Eastern Front 1914-1917 Online

Authors: Norman Stone

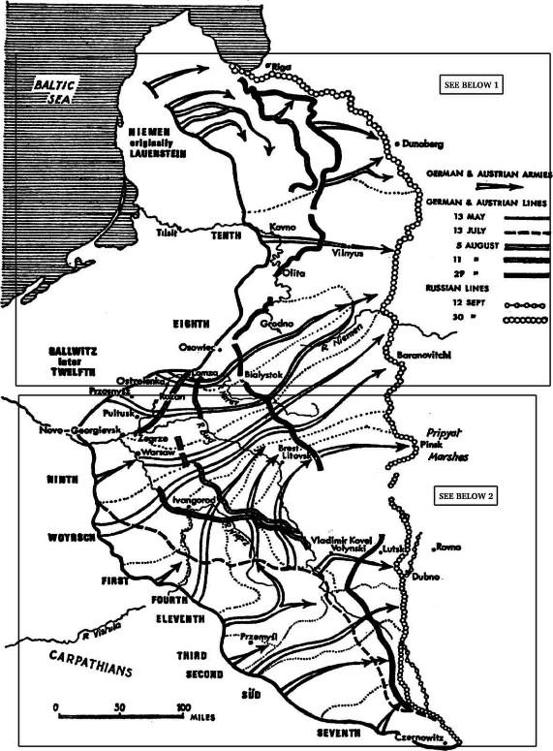

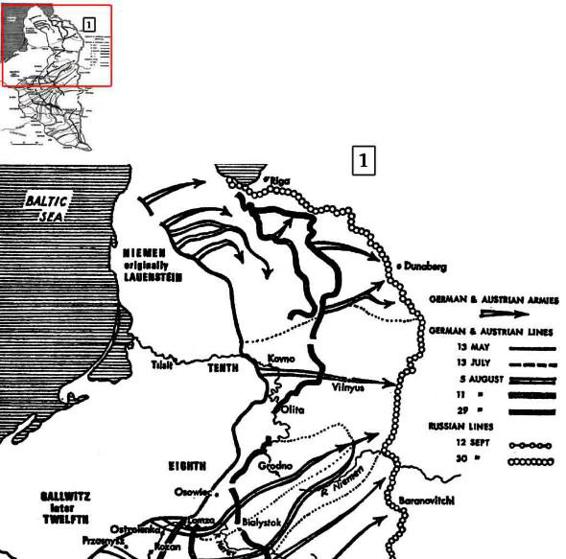

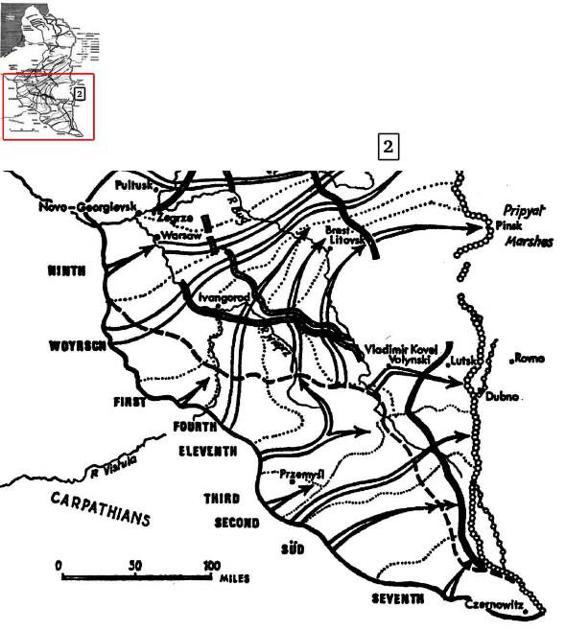

The Central Powers’ triple offensive of 1915 and the Russian retreat.

now blowing in Poland. The Russian armies of the central theatre stood in a salient, of which East Prussia and the newly-lost Galicia formed the northern and southern sides. It was now possible for the Central Powers to mount a pincer-movement from East Prussia and Galicia—much as Conrad von Hötzendorf had wanted in August 1914—with a view to surrounding the Russian troops of the central theatre. The danger in the northern sector was all the greater because Alexeyev had been forced to transfer troops on a considerable scale to the south, as Ivanov’s front collapsed. In May, Alexeyev had had two-thirds of the troops in this theatre, but by mid-June he had lost twelve divisions, not counting 3. Caucasus Corps and a second-line division sent from

Stavka

’s reserve; and by 5th July, with the departure of four corps to make up a new army (Olokhov’s) against Mackensen, Alexeyev’s troops were reduced to forty-three infantry divisions and thirteen and a half cavalry divisions out of a total 116 and thirty-five and a half operating on the eastern front. The south-western front now contained thirty out of forty-nine and a half army corps, where in May it had had nineteen. To give better central control to the front as a whole, Alexeyev was now given charge of the whole of the Polish salient, instead of half of it, as before. But the troops of his old front, from west of the middle Vistula to north-west of the Narev, appeared to be very exposed to German thrusts.

Voices were raised, first timorously in mid-June, and then with increasing shrillness, in favour of retreat. ‘The foremost theatre’—the Polish salient—ought to be given up, because the front could be pierced, and the troops of I, II and IV Armies surrounded. A bold policy of retreat, put into effect in mid-June, might indeed have saved the Russian army from the disasters of summer 1915, and loss of hundreds of thousands of prisoners. But

Stavka

shrank from such a policy. It would mean letting the Germans take Poland. It would mean abandoning forward positions at the very moment the western Powers were likely to take the Dardanelles; Russia would lose her arguments for eventual annexation of Constantinople; moreover, if the Italians, now, broke out into Austrian territory, Russia would maybe lose control of areas the future of which she desired to shape. The French and British talked of launching an offensive in the west, with quantities of artillery that the Russians regarded as fabulous, and a Russian retreat could not therefore be opportune.

Moreover, on the ground there were solid arguments against retreat: the fortresses of Poland.

11

The men surrounding Grand Duke Nicholas had strongly opposed Sukhomlinov’s proposal to scrap these; they were now foist with the consequences of their own proposals to retain them. Novogeorgievsk, down-river from Warsaw, was a great fortress, with 1,680 guns, and almost a million shells. Ivangorod, though smaller, had,

been restored in the course of the war, and had many partisans because of its stout defence in the previous October. These two, with Grodno, Kovno, Osowiec and Dvinsk, contained 5,200 older fortress-cannon and 3,148 modern high-trajectory guns, as well as 880 large-calibre modern cannon. These fortresses had been constructed with just the present emergency in view, and it seemed precipitate to abandon them (and thus confess the enormity of pre-war errors) at the very moment they were required. Moreover, Schwarz in Ivangorod and Sveshnikov in Osowiec could point to singular successes against the Germans, in October 1914 and February-March 1915, while in any event the evacuation of fortresses could take an unconscionable amount of rolling-stock—Prince Yengalychev, governor of Warsaw, said that he would need 2,000 trains to evacuate Warsaw, and 1,000 for Novogeorgievsk, quantities which supply of the ineffable horse obviously forbade. It would in any case be highly embarrassing to give up fortresses at the very moment Sukhomlinov was being charged with high treason for proposing the same thing years before the war. Of course, the fate of fortresses in western Europe should have shown

Stavka

the folly of its course: Liège, Namur, Maubeuge, Antwerp had collapsed after at most a few weeks’ defence, and the French ability to hold the town of Verdun was based on correct recognition that the forts ostensibly protecting it were just concrete traps, offering obvious targets for the Germans’ heavy artillery, and preventing the defence from behaving flexibly. But

Stavka

knew better: there would be an attempt to hold the fortresses.

There were of course occasional hints of realism. Palitsyn, who had been summoned to advise

Stavka

, thought that ‘soberly-considered, it is a mistake for us to fight for the foremost theatre’. But even Palitsyn swung the other way when news from the front seemed to improve.

Stavka

sent him to Ivangorod with an instruction to the commandant to prepare for retreat, but he was told to add, personally, that there should be no great hurry in such preparations. The front commands were meanwhile rapped over the knuckles for suggesting that they might retreat. Ivanov had proposed at least withdrawing the armies west of the Vistula to lines where retreat would be easier, a shortening of the front that would allow him to take some of its troops for reserve.

Stavka

’s response was to give responsibility of this part of the front to Alexeyev. But Alexeyev too thought retreat would be sensible. His I and XII Armies holding lines north-west of the Narev were exposed to a German attack, of which there were already signs. He proposed taking them back to the Narev, again to create reserves on a shorter line.

Stavka

thought that this would cause the German attack Alexeyev feared, and told him to leave the troops where they were. On 25th June Yanushkevitch recommended

construction of strong lines, one after another, ‘on which our troops can successfully hold out, dragging the enemy into battle for every square foot of land’. Characteristically, nothing much was done to prepare such lines: men disagreed as to where they might be dug, lacked man-power to dig them, and in any case thought they would be bad for morale. Some desultory earth-shifting alone followed

Stavka

’s precepts: the lines offered obvious targets for German artillery, yet little protection for men inside them. Although many highly-placed officers knew, in their heart of hearts, that the shell-crisis, the rifle-crisis, the strategically unfavourable layout of Poland, and the moral crisis of the army could only add up to retreat, nothing much was done to prepare for it. ‘The masterly Russian retreat of summer 1915’ was a legend, invented by the Central Powers to excuse their own blunders. The Russian supreme command simply waited on events, or rather hoped there would be none.

12

Stavka

’s decision to retreat came piece-meal and reluctantly, as a consequence of German action. In July 1915 Falkenhayn elected to launch a double attack on Poland, from north and south, as well as to maintain pressure in Courland. The Central Powers, too, had suffered from indecision, but they needed success, and were therefore prepared to go on against Russia, where originally they had meant to stop on the San. Falkenhayn temporarily forgot his plans for an offensive against Serbia, to clear the way to Turkey, while Conrad also shelved his plans for an offensive against Italy. Even so, Falkenhayn’s aims were always very limited against Russia. He did not want to commit himself to an open-ended Russian campaign, for he feared another 1812: ‘The Russians can retreat into the vastness of their country, and we cannot go chasing after them for ever and ever’;

13

there would be huge supply-problems, and the forces were in any case too weak. Falkenhayn did not believe that Germany could win a two- or three-front war. One of the major enemies must be led to a separate peace; and throughout 1915, he made attempts at a separate peace with Russia, through a Danish intermediary, Andersen. He received dusty answers. Just the same, both he and Conrad were interested in ‘building golden bridges’ to Russia—no doubt, over the Golden Horn—and their strategy was designed at least as much to show German invincibility as to bring about a complete destruction of Russia—or so Falkenhayn claimed. Ludendorff had different ideas. He was impressed at the Russians’ crumbling in Courland, and thought that a bold stroke from the north-east would work. Falkenhayn preferred his own limited strategy of attrition, and the most he would undertake was an attack over the Narev towards Warsaw. The Russians would lose Poland, and many thousands of men. They would not lose much territory—which was as well, for the Germans would not have to lengthen

their lines of supply, and the Russians would not be stimulated into defence to the uttermost. By 2nd July this plan, after considerable objection from Ludendorff, was agreed to. Mackensen’s group would attack from the Austro-Hungarian border, and, from the front north of Warsaw, a strong group under Gallwitz would attack. On the map, this did not look like an ambitious pincer-movement such as Ludendorff, and, with some reservations, Conrad, hoped for. But at bottom it reflected a much more sensible view of the war.

Three German operations therefore proceeded: Galicia, the Narev, and Courland. Already, Russian reserves had been greatly dispersed, and the three-front attack proved to be an excellent way of dispersing them still more. In the Galician theatre, the Central Powers’ forces grouped as

Heeresgruppe Mackensen

were to move north, straight towards Brest-Litovsk. Conrad had different ideas—wanting some of this force to go to the north-east, where something of a ‘pincer-movement’ could be effective, the rear of the Russians in Poland taken. Some cavalry, and an Austrian army, were vaguely ear-marked for this purpose. Falkenhayn thought that a stroke of this type would merely end up in supply-difficulties, since it had to cross the great marshes of the Pripyat; and he had little faith in the ability of Austrian troops to carry out an ambitious scheme of this type—doubts that the event substantially confirmed. Mackensen himself was against fancy manoeuvres. He had thirty-three and a half infantry and two cavalry divisions in his own Army Group, with eight and three in the Austrian I Army on his right. He faced thirty-three infantry and six and a half cavalry divisions, many of them fresh troops, and he had no doubt that ambitious flanking-schemes in the east would simply mean a subtraction of force that he could not afford. If the flanking operation could make much speed, no doubt it would be different; but the roads were few, and mobility bound to be too little. ‘As before’, he later said, ‘I reckon that a strong centre is suitable for attack, as it will give us the best chance for successful advance.’ His method was to assemble a great weight of artillery in his centre. Hitherto, this had worked well enough, and it continued to do so. The Russians not only failed to make a strategic retreat at this time; they also had no notion of tactical retreat, and yet the trenches they built were primitive. In these circumstances, the Germans’ bombardment was always extremely destructive. A British observer wrote that at Trawniki, in late July, the Guard and 2. Siberian Corps had been bombarded from 2 a.m. until noon, one Siberian division was ‘annihilated’. The Guard did stay put under heavy fire, ‘whereas in other corps the men run away and are destroyed by shrapnel’.

14

He added, ‘It is unfair to ask any troops to stand this nerve-wracking unless they have a regular rabbit-warren of trenches.’

The Russian trenches were ‘graves’. In these circumstances, Mackensen’s bludgeon seemed a good policy to use, and Falkenhayn went ahead. Mackensen assembled troops on the Galician border, contained the attack of the four corps that Alexeyev had sent south—they won a success near Kraśnik against the Austrian IV Army, incontinently advancing—and in mid-July attacked towards Lublin and Cholm.