The Element (10 page)

Authors: Ken Robinson

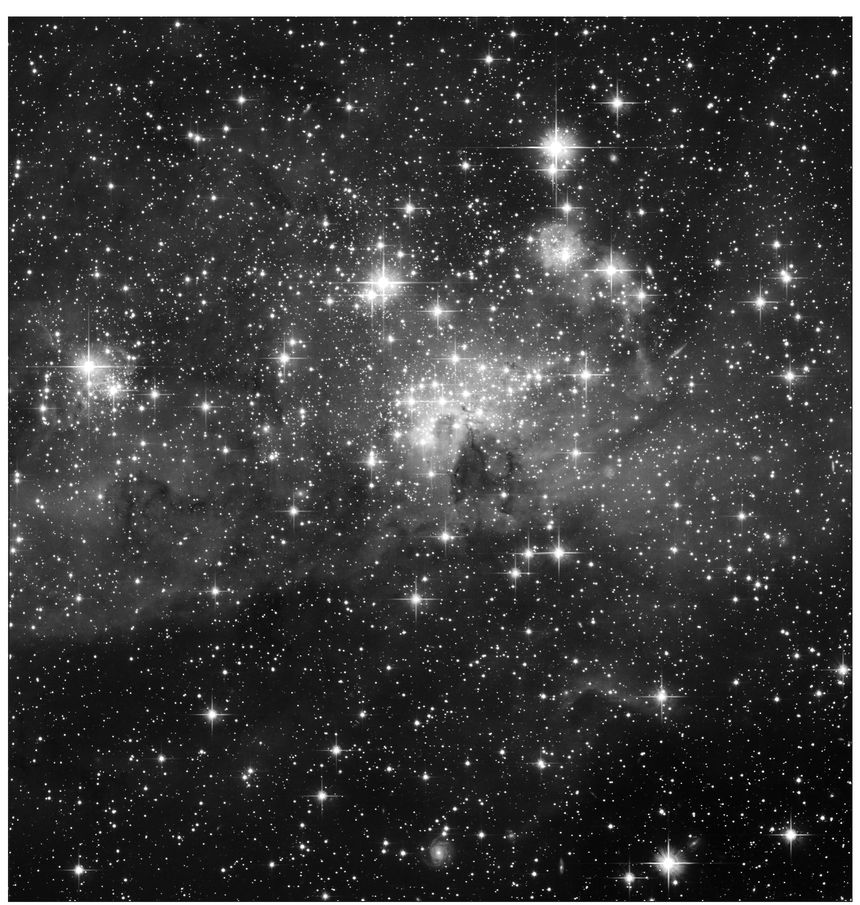

On this scale, the Sun is a grain of sand and Arcturus is a kumquat. Antares, by the way, is the fifteenth-brightest star in the sky. It is more than a thousand light-years away. Astronomers would say it is

only

a thousand light-years away. A light-year, you’ll recall, is the distance that a beam of light travels in a year. That’s far. So a thousand light-years sounds impressive, especially if you’re Pluto. But it’s actually not that not much in galactic terms. Compare it with this final image, which is from the Hubble telescope.

only

a thousand light-years away. A light-year, you’ll recall, is the distance that a beam of light travels in a year. That’s far. So a thousand light-years sounds impressive, especially if you’re Pluto. But it’s actually not that not much in galactic terms. Compare it with this final image, which is from the Hubble telescope.

This is an image of the Magellanic Cloud, one of the closest galaxies to our Milky Way, a near neighbor in the scheme of things. Scientists estimate the Magellanic Cloud to be about 170,000 light-years across. It’s almost impossible to picture the size of Earth on this scale. It’s pitifully, unimaginably, undetectably small.

And yet . . .

We can take away some encouraging things from this. One is a bit of perspective. I mean, really, whatever you woke up worrying about this morning, get over it. How important in the greater scheme of things can it possibly be? Make your peace and move on.

The second is this. At first glance, these images do indeed suggest that the answer to Russell’s first question might be yes. We certainly do seem to be clinging to the face of an extraordinarily small and unimportant planet. But that’s not really the end of the story. We may well be small and insignificant. However, uniquely among all known species on Earth—or anywhere else, to our knowledge—we are able to do something remarkable. We can conceive of our insignificance.

Using the power of imagination, someone made the images I just showed you. Using this same power, I’m able to write about them and have them published, and you’re able to understand them. The fact, too, is that as a species we produced the Hamlet of which Russell speaks—as well as Mozart’s Mass in C, the Blue Mosque, the Sistine Chapel, the Renaissance, Las Vegas, the Silk Road, the poetry of Yeats, the plays of Chekhov, the blues, rock and roll, hip-hop, the theory of relativity, quantum mechanics, industrialism,

The Simpsons

, digital technology, the Hubble telescope, and the whole dazzling cornucopia of human achievements and aspirations.

The Simpsons

, digital technology, the Hubble telescope, and the whole dazzling cornucopia of human achievements and aspirations.

I don’t mean to say that no other species on Earth has any form of imaginative ability. But certainly none comes close to showing the complex abilities that flow from the human imagination. Other species communicate, but they don’t have laptops. They sing, but they don’t produce musicals. They can be agile, but they didn’t come up with Cirque du Soleil. They can look worried, but they don’t publish theories on the meaning of life and spend their evenings drinking Jack Daniel’s and listening to Miles Davis. And they don’t meet at water holes, poring over images from the Hubble telescope and trying to figure out what those might mean for themselves and all other hyenas.

What accounts for these yawning differences in how humans and other species on our small planet think and behave? My general answer is imagination. But this is really about the much more sophisticated evolution of the human brain and the highly dynamic ways in which it can work. The dynamics of human intelligence account for the phenomenal creativity of the human mind. And our capacity for creativity allows us to rethink our lives and our circumstances—and to find our way to the Element.

The Power of CreativityImagination is not the same as creativity. Creativity takes the process of imagination to another level. My definition of creativity is “the process of having original ideas that have value.” Imagination can be entirely internal. You could be imaginative all day long without anyone noticing. But you would never say that someone was creative if that person never did anything. To be creative you actually have to do something. It involves putting your imagination to work to make something new, to come up with new solutions to problems, even to think of new problems or questions.

You can think of creativity as applied imagination.

You can be creative at anything at all—anything that involves using your intelligence. It can be in music, in dance, in theater, in math, science, business, in your relationships with other people. It is because human intelligence is so wonderfully diverse that people are creative in so many extraordinary ways. Let me give you two very different examples.

In 1988, former Beatle George Harrison had a solo album coming out. The album featured a song called “This is Love” that both Harrison and his record company felt could be a big hit. A common practice in those pre-download days was for the artist to accompany a single release with a B-side—a song that didn’t appear on the album the single appeared on—as added value for consumers. The only problem in this case was that Harrison didn’t have a recording to use as a B-side. However, Bob Dylan, Roy Orbison, Tom Petty, and Jeff Lynne were all spending time with him in the Los Angeles area, where Harrison was living at the time.

As Harrison came up with the bones of the song he wanted to record, he realized that Lynne was already working with Orbison. Harrison soon asked Dylan and Petty to join them and to sing along on the song’s chorus. In a casual setting with the minimal pressure associated with recording a B-side, these five rock legends generated “Handle with Care,” one of the most memorable songs of Harrison’s post-Beatle career.

When Harrison played the song a few days later for Mo Ostin, chairman of Warner Brothers Records, and Lenny Waronker, head of A&R, the two were stunned. Not only was the song much too good to serve as a lowly B-side, but the collaboration generated a sound at once easygoing and brilliant that begged for a grander platform. Ostin and Waronker wondered to Harrison if the team that created “Handle with Care” could generate an entire album. Harrison found the idea intriguing and took it back to his friends.

Some logistical items needed addressing. Dylan was going out on a long tour in two weeks, and getting everyone in one place after that was going to be a problem. The five decided to squeeze whatever they could into the time they had before Dylan’s departure. Using a friend’s studio, they laid down the tracks for the entire album. They didn’t have months to dedicate to polishing the songwriting, doing dozens of alternate takes, or worrying over a guitar part. Instead, they relied on something much more innate—the creative spark generated by five distinctive musical voices joining together.

They all collaborated on songs. Each donated vocal harmonies, guitar lines, and arrangements. They fed off each other, goaded each other, and, most importantly, had a great time. The result was a recording that was both casual—the songs seem invented on the spot—and unmistakably classic. In fitting with the relaxed nature of the project, the five decided to downplay their stardom and to call their makeshift band the Traveling Wilburys. The album they recorded went on to sell five million copies and spawn multiple hit singles, including “Handle with Care.”

Rolling Stone

magazine named

The Traveling Wilburys

one of the “100 Best Albums of All Time.” I think that this is a great example of the creative process at work.

Rolling Stone

magazine named

The Traveling Wilburys

one of the “100 Best Albums of All Time.” I think that this is a great example of the creative process at work.

Here’s another one that seems completely different.

In the early 1960s, an unknown student at Cornell University threw a plate into the air in the university restaurant. We don’t know what happened after that to the student or to the plate. The student may have caught the plate with a smile, or it may have shattered on the floor. Either way, this would not have been an extraordinary event but for the fact that someone extraordinary happened to be watching it.

Richard Feynman was an American physicist, and one of the undisputed geniuses of the twentieth century. He was famous for his groundbreaking work in several fields including quantum electrodynamics and nanotechnology. He was also one of the most colorful and admired scientists of his generation, a juggler, a painter, a prankster, and an exuberant jazz musician with a particular passion for playing the bongos. In 1965, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics. He says this was partly because of the flying plate.

“That afternoon while I was eating lunch, some kid threw up a plate in the cafeteria,” Feynman said. “There was a blue medallion on the plate, the Cornell sign, and as he threw up the plate and it came down, the blue thing went around and it seemed to me that the blue thing went around faster than the wobble, and I wondered what the relation was between the two. I was just playing, no importance at all, but I played around with the equations of motion of rotating things, and I found out that if the wobble is small the blue thing goes around twice as fast as the wobble goes round.”

Feynman jotted some thoughts down on his napkin, and after lunch, he got on with his day at the university. Some time later, he looked again at the napkin and carried on playing with the ideas he’d sketched out on it.

“I started to play with this rotation, and the rotation led me to a similar problem of the rotation of the spin of an electron according to Dirac’s equation, and that just led me back into quantum electrodynamics, which was the problem I had been working on. I kept continuing now to play with it in the relaxed fashion I had originally done and it was just like taking the cork out of a bottle—everything just poured out, and in very short order I worked the things out for which I later won the Nobel Prize.”

Apart from the fact that they both spin around, what do making records and understanding electrons have in common that can help us understand the nature of creativity? As it happens, quite a lot.

Creative DynamicsCreativity is the strongest example of the dynamic nature of intelligence, and it can call on all areas of our minds and being.

Let me begin with a rough distinction. I said earlier that many people think they’re not creative because they don’t know what’s involved. This is true in two different ways. The first is that there are some general skills and techniques of creative thinking that everyone can learn and can apply to nearly any situation. These techniques can help in generating new ideas, in sorting out the useful ones from the less useful ones, and in removing blocks to new thinking, especially in groups. I think of these as the skills of general creativity, and I’m going to say more about them in the chapter on education. What I want to discuss in this chapter is personal creativity, which in some ways is very different.

Faith Ringgold, the Traveling Wilburys, Richard Feynman, and many of the other people in this book are all highly creative people in their own unique ways. They work in different domains, and individual passions and aptitudes drive them. They have found the work they love to do, and discovered a special talent for doing it. They are in their Element, and this drives their personal creativity. Having some understanding of how creativity works in general can be instructive here.

Creativity is a step beyond imagination because it requires that you actually do something rather than lie around thinking about it. It’s a very practical process of trying to make something original. It may be a song, a theory, a dress, a short story, a boat, or a new sauce for your spaghetti. Regardless, some common features pertain.

The first is that it is a process. New ideas do sometimes come to people fully formed and without the need for much further work. Usually, though, the creative process begins with an inkling—like Feynman watching the wobble of the plate or George Harrison’s first idea for a song—which requires further development. This is a journey that can have many different phases and unexpected turns; it can draw on different sorts of skills and knowledge and end up somewhere entirely unpredicted at the outset. Richard Feynman eventually won the Nobel Prize in Physics, but they didn’t give it to him for the napkin he’d scribbled on over lunch.

Creativity involves several different processes that wind through each other. The first is generating new ideas, imagining different possibilities, considering alternative options. This might involve playing with some notes on an instrument, making some quick sketches, jotting down some thoughts, or moving objects or yourself around in a space. The creative process also involves developing these ideas by judging which work best or feel right. Both of these processes of generating and evaluating ideas are necessary whether you’re writing a song, painting a picture, developing a mathematical theory, taking photographs for a project, writing a book, or designing clothes. These processes don’t come in a predictable sequence. Instead, they interact with each other. For example, a creative effort might involve a great deal of idea generation while holding back on the evaluation at the start. But overall, creative work is a delicate balance between generating ideas and sifting and refining them.

Because it’s about making things, creative work always involves using media of some sort to develop ideas. The medium can be anything at all. The Wilburys used voices and guitars. Richard Feynman used mathematics. Faith Ringgold’s media were paints and fabrics (and sometimes words and music).

Other books

Zero To Sixty (BWWM, Sports, Billionaire) by Tamara Adams

Here Be Monsters by Anthony Price

Where the Lotus Flowers Grow by MK Schiller

A Street Girl Named Desire: A Novel by Blue, Treasure E.

Xenia’s Renegade by Agnes Alexander

The Pelican Bride by Beth White

Midnight Heat (Firework Girls #2) by J. L. White

The Mountains Rise by Michael G. Manning

Deep Focus by McCarthy, Erin

Darkness Falls (Darkness Series Book 3) by Drake, J.L.