the Emigrants (11 page)

Authors: W. G. Sebald

OASIS D HELIOPOLIS,

CASINO

been made at rather short notice, said Aunt Fini, and from what Uncle Adelwarth told me it was an attempt to regain the past, an attempt that appears to have failed in every respect. The start of Cosmo's second serious nervous breakdown appears to have been connected with a German film about a gambler that was screened in New York at the time, which Cosmo described as a labyrinth devised to imprison him and drive him mad, with all its mirror reversals. He was particularly disturbed by an episode towards the end of the film in which a one-armed showman and hypnotist by the name of Sandor Weltmann induced a sort of collective hallucination in his audience. From the depths of the stage (as Cosmo repeatedly described it to Ambros) the mirage image of an oasis appeared. A caravan emerged onto the stage from a grove of palms, crossed the stage, went down into the auditorium, passed amongst the spectators, who were craning round in amazement, and vanished as mysteriously as it had appeared. The terrible thing was (Cosmo insisted) that he himself had somehow gone from the hall together with the caravan, and now could no longer tell where he was. One day, not long after, Aunt Fini continued, Cosmo really did disappear. I do not know where they searched for him, or for how long, but know that Ambros finally found him two or three days later on the top floor of the house, in one of the nursery rooms that had been locked for years. He was standing on a stool, his arms hanging down motionless, staring out at the sea where every now and then, very slowly, steamers passed by, bound for Boston or Halifax. When Ambros asked why he had gone up there, Cosmo said he had wanted to see how his brother was. But he never did have a brother, according to Uncle Adelwarth. Soon after, when Cosmo's condition had improved to some extent, Ambros accompanied him to Banff in the Canadian Rockies, for

the good air, on the advice of the doctors. They spent the whole summer at the famous Banff Springs Hotel. Cosmo was then like a well-behaved child with no interest in anything and Ambros was fully occupied by his work and his increasing concern for his charge. In mid October the snows began. Cosmo spent many an hour looking out of the tower window at the vast pine forests all around and the snow swirling down from the impenetrable heights. He would hold his rolled-up handkerchief clenched in his fist and bite into it repeatedly out of desperation. When darkness fell he would lie down on the floor, draw his legs up to his chest and hide his face in his hands. It was in that state that Ambros had to take him home and, a week later, deliver him to the Samaria Sanatorium at Ithaca, New York, where that same year, without saying a word or moving a muscle, he faded away.

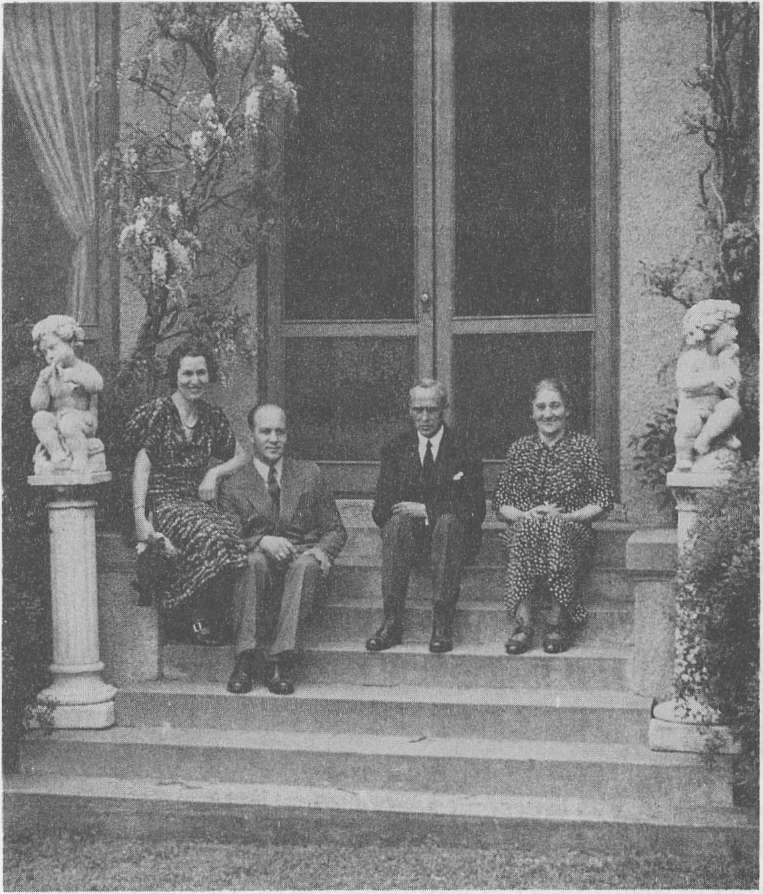

These things happened more than half a century ago, said Aunt Fini. At that time I was at the Institute in Wettenhausen and knew nothing of Cosmo Solomon, nor of our mother's brother who had emigrated from Gopprechts. It was a long time before I learnt anything of Uncle Adelwarth's earlier days, even after I arrived in New York, and despite the fact that I was always in touch with him. After Cosmo's death, he became butler in the house at Rocky Point. From 1930 to 1950 I regularly drove out to Long Island, either alone or with Theo, as an extra help when big occasions were being prepared, or simply to visit. In those days, Uncle Adelwarth had more than half a dozen servants under him, not counting the gardeners and chauffeurs. His work took all his time and energy. Looking back, you might say that Ambros Adelwarth the private man had ceased to exist, that nothing was left but his shell of decorum. I could not possibly have imagined him in his shirtsleeves, or in stockinged feet without his half-boots, which were unfailingly polished till they shone, and it was always a mystery to me when, or if, he ever slept, or simply rested a little. At that time he had no interest in talking about the past at all. All that mattered to him was that the hours and days in the Solomons' household should pass without any disruption, and that the interests and ways of old Solomon should not conflict with those of the second Mrs Solomon. From about the time he was thirty-five, said Aunt Fini, this became particularly difficult for Uncle Adelwarth, given that old Solomon had announced one day, without preamble, that he would no longer be present at any dinners or gatherings whatsoever, that he would no longer have anything at all to do with the outside world, and that he was going to devote himself entirely to growing orchids, whereas the second Mrs Solomon, who was a good twenty years younger than him, was known far beyond New York for her weekend parties, for which guests generally arrived on Friday afternoons. So on the one hand Uncle Adelwarth was increasingly kept busy looking after old Solomon, who practically lived in his hothouses, and on the other he was fully occupied in pre-empting the second Mrs Solomon's characteristic liking for tasteless indiscretions. Presumably the demands made by these twofold duties wore him down more, in the long term, than he admitted to himself, especially during the war years, when old Solomon, scandalized by the stories that still reached him in his seclusion, took to spending most of his time sitting wrapped in a travelling rug in an overheated glasshouse amidst the pendulous air-roots of his South American plants, uttering scarcely a syllable beyond the bare essentials, while Margo Solomon persisted in holding court. But when old Solomon died in his wheelchair in the early months of 1947, said Aunt Fini, something curious happened: now it was Margo who, having ignored her husband for nearly ten years, could hardly be persuaded to leave her room. Almost all the staff were discharged. Uncle Adelwarth's principal duty was now to look after the house, which was well-nigh deserted and largely draped with white dust-sheets. That was when Uncle Adelwarth began, now and again, to recount to me incidents from his past life. Even the least of his reminiscences, which he fetched up very slowly from depths that were evidently unfathomable, was of astounding precision, so that, listening to him, I gradually became convinced that Uncle Adelwarth had an infallible memory, but that, at the same time, he scarcely allowed himself access to it. For that reason, telling stories was as much a torment to him as an attempt at self-liberation. He was at once saving himself, in some way, and mercilessly destroying himself. As if to distract me from her last words, Aunt Fini picked up one of the albums from the side table. This, she said, opening it and passing it over to me, is Uncle

Adelwarth as he was then.

As

you can see, I am on the left with Theo, and on the right, sitting beside Uncle, is his sister Balbina, who was just then visiting America for the first time. That was in May 1950. A few months after the picture was taken, Margo Solomon died of the complications of Banti's disease. Rocky Point passed to various beneficiaries and was sold off, together with all the furniture and effects, at an auction that lasted several days. Uncle Adelwarth was sorely affected by the dispersal, and a few weeks later he moved into the house at Mamaroneck that old Solomon had made over to him before he died. There is a picture of the living room on one of the next pages, said Aunt Fini. The whole house was always very neat and tidy, down to the last detail, like the room in this photograph. Often it seemed to me as if Uncle

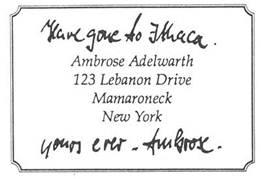

Adelwarth was expecting a stranger to call at any moment. But no one ever did. Who would, said Aunt Fini. So I went over to Mamaroneck at least twice a week. Usually I sat in the blue armchair when I visited, and Uncle sat at his bureau, at a slight angle, as if he were about to write something or other. And from there he would tell me stories and many a strange tale. At times I thought the things he said he had witnessed, such as beheadings in Japan, were so improbable that I supposed he was suffering from Korsakov's syndrome: as you may know, said Aunt Fini, it is an illness which causes lost memories to be replaced by fantastic inventions. At any rate, the more Uncle Adelwarth told his stories, the more desolate he became. After Christmas '52 he fell into such a deep depression that, although he plainly felt a great need to talk about his life, he could no longer shape a single sentence, nor utter a single word, or any sound at all. He would sit at his bureau, turned a little to one side, one hand on the desktop pad, the other in his lap, staring steadily at the floor. If I talked to him about family matters, about Theo or the twins or the new Oldsmobile with the white-walled tyres, I could never tell if he were listening or not. If I tried to coax him out into the garden, he wouldn't react, and he refused to consult a doctor, too. One morning when I went out to Mamaroneck, Uncle Adelwarth was gone. In the mirror of the hall stand he had stuck a visiting card with a message for me, and I have carried it with me ever since. Have gone to Ithaca. Yours

ever - Ambrose. It was a while before I understood what he meant by Ithaca. Needless to say, I drove over to Ithaca as often as I could in the weeks and months that followed. Ithaca is in a beautiful part of the country. All around there are forests and gorges through which the water rushes down towards the lake. The sanatorium, which was run by a Professor Fahnstock, was in grounds that looked like a park. I still remember, said Aunt Fini, standing with Uncle Adelwarth by his window one crystal-clear Indian Summer morning. The air was coming in from outside and we were looking over the almost motionless trees towards a meadow that reminded me of the Altach marsh when a middle-aged man appeared, holding a white net on a pole in front of him and occasionally taking curious jumps. Uncle Adelwarth stared straight ahead, but he registered my bewilderment all the same, and said: It's the butterfly man, you know. He comes round here quite often. I thought I caught an undertone of mockery in the words, and so took them as a sign of the improvement that Professor Fahnstock felt had been effected by the electroconvulsive therapy. Later in the autumn, though, the extent of the harm that had been done to Uncle's spirit and body was becoming clearer. He grew thinner and thinner, his hands, which used to be so calm, trembled, his face became lopsided, and his left eye moved restlessly. The last time I visited Uncle Adelwarth was in November. When it was time for me to leave, he insisted on seeing me to my car. And for that purpose he specially put on his

paletot

with the black velvet collar, and his Homburg. I still see him standing there in the driveway, said Aunt Fini, in that heavy overcoat, looking very frail and unsteady.