The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 (38 page)

Read The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 Online

Authors: John Darwin

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Modern, #General, #World, #Political Science, #Colonialism & Post-Colonialism, #British History

The idea of India

Behind the slogans, schemes and manoeuvres of these decades lay a deeper issue: the idea of India. In an age of such furious change – in communications technology, geopolitical assumptions, social mobility, cultural hierarchy, religious allegiance, economic structure, political order – in India and beyond, it was hardly surprising that the sub-continent evoked widely different and sharply contested visions of its political and cultural future. The idea of India was being made and re-made with exceptional urgency. New formulas were concocted. New audiences were sought. The stakes were rising.

In London, the official and semi-official idea of India was predictably instrumental. As India grew more valuable, the costs of instability went up, and imperial supervision became more rigorous. If India's

relative

economic importance had slipped with the huge growth of British trade and investment in the Americas after 1900, it was still the largest export market for Britain's largest export. London's oversight (rather than Civilian rule) was Lancashire's guarantee of an open door for its cotton products. The continuing expansion of Indian trade and the ever-growing frequency of its communications with Britain suggested that India's place in the British pattern of trade, investment and payments was as important as ever. On the geostrategic front, the trend seemed even stronger. London's view of India had always been refracted through the prism of its military assets. India was the strategic reserve for the British system east (and sometimes west) of Suez. In 1899, (British) troops rushed from India (not distant Britain) had stopped the Boer dash for the sea and staved off disaster in the early phase of the South African War. As the division of the world into spheres and colonies speeded up, and the geopolitics of partition spread across Asia, geostrategic control over India came to seem more and more critical to the British world-system. This was the point of Curzon's address on ‘India's place in the Empire’. This was the point made by

The Times

in 1911, when it drew the connection between command of India and command of the sea. ‘India stands right across the greatest highway in the world’, it proclaimed (with some hyperbole). ‘It is the centre of the East…The Power which holds India must of necessity command the sea. Supreme sea-power would be as difficult to maintain without control of India, as control of India without command of the sea. It is…the centre of Imperial defence.’

115

Of course, the view from London was heavily coloured by the vision of oriental backwardness so skilfully promoted in the literature of Anglo-India. But implicit in London's ‘idea’ was an unsentimental regard for India's utility and an indifference to those intra-Indian affairs that had no imperial significance. The Civilians would be backed to the hilt if India's imperial ‘duty’ was threatened by its politicians. But London might be willing to cooperate with ‘loyal’ Indian ‘moderates’, especially at the provincial level where

its

interests were not at risk. There was always the

claque

of Anglo-India's friends at home to face. But, if the Civilian regime seemed a bar to modernising India

imperially

, or to the partnership of its native elites in some larger imperial purpose, it might yet find its privileges cut down by the London government. Before 1914, for all the sound and fury of Morley's reforms, there was little sign of this. The Civilians could not be replaced as the guardians of the imperial stake while its strategic component was growing so remorselessly in value.

Hence, perhaps, the continuing vigour and confidence with which the Civilians’ idea of India was propagated. The Civilians had had to come to terms since the 1880s with the growth of an educated class and with a vociferous press, both of which challenged the dogmas of its rule. Their reaction had been to emphasise, by ‘scientific’ inquiry and with wider publicity, their vision of India as a cultural and political mosaic, a riot of castes, communities, religions and races, teetering on the brink of violent disorder. More pragmatically, they modified their bureaucratic despotism by limited devolution at local level and by the careful definition of interest groups with privileged access to authority and (after 1892) with seats on provincial councils. Under pressure from Congress and London, this idea had expanded into something more grandiose: India as a confederacy knit together by Civilian rule and the neo-feudal loyalty of its landed classes. With provincial devolution, ‘conservative’ (rather than ‘Congress’) India would be brought to the fore. The educated class would be revealed as one community among many, special perhaps in its claims, but not dominant in its influence. The horizontal and vertical links in this emergent India would remain under Civilian control. An untrammelled authority at the Indian centre would ensure that the Civilian Raj could pay the imperial dividend, the secret of its lease of power from London. In the meantime, it made sense for the Raj to identify itself more openly with Indian interests, where the ‘dividend’ was not involved. In 1913, the Viceroy, Lord Hardinge, expressed his government's sympathy for the Ottoman Empire (reeling from its Balkan defeats) as a fellow ‘Muhammadan power’.

116

He promised to take up the grievances of Indian communities in settler Africa.

117

‘Anglo-India’ and ‘Indian-India’ would be reconciled.

On the Congress politicians the travails of political struggle since the 1880s had also left their mark. But to a remarkable extent the core of their programme survived unchanged. Like European nationalists, the Congress leaders saw in the educated class a proxy for the nation. They saw themselves as trustees of the Indian idea. Their vision of India was (politically at least) to remake it along Gladstonian lines. The object of the Congress, declared its president in 1912, was ‘to create a nation’ whose citizens would be ‘members of a world-wide empire’. ‘Our great aim is to make the British Government the National Government of the British Indian people.’

118

India was to be a British Indian nation, inspired by the ideals of British-style Liberalism. The apparatus of the Raj would be the scaffolding of Indian nationhood, just as the adoption of British values would be the secret of self-rule. Pressing the old case for easier Indian entry into the ranks of the Civilians, Motilal Nehru insisted that, even if Indian candidates were locally chosen, they should still be sent to Britain to complete their education: ‘to acquire those characteristics which are essentially British and…absolutely necessary in the interests of good government in India’.

119

It was ‘axiomatic’, he went on, that the administration in India ‘must have a pronounced British tone and character and too much stress cannot be laid on Indians acquiring that character as a habit’.

120

It was no accident that Motilal sent his son (Jawaharlal) to Harrow and Cambridge: he was meant for the Civil Service, not Congress.

In retrospect, we can see that each of these ideas of India received in this period a decisive check. By 1914 they were all at stalemate. A new cadre of imperially minded Indians, ready and willing to do India's imperial duty, was the white hope of advanced opinion in Britain. If the British world-system was not to weaken or stagnate, India's contribution must grow greater, its role more dynamic, its leaders more receptive to their imperial task. In reality, there was not the smallest sign that the most moderate of the Indian moderates would agree to India's

existing

imperial burdens once self-government was granted. Like it or not, London would find itself bound to the Civilian Raj. The unofficial ties of sympathy between the Imperial centre and its Indian friends would be fretted by this dilemma. As for the Civilians, their hope of embedding their rule in Indian sympathies, fusing their autocracy with Indian conservatism, had (as it turned out) little chance of success. It depended too heavily upon stifling the appeal of Indian nationalism in the educated class and on rallying new groups and interests to provincial institutions without the means to satisfy their wants. For the ‘British Indian nationalists’ of the Congress, the future was just as gloomy. Indeed, they were trapped in a paradox. Without mobilising a larger following (the course rejected in 1907) they had little hope of a breakthrough at the provincial (let alone the All-India) level. Without wresting more power and patronage from the Civilians, they had few means of widening the appeal of the ‘manly liberalism’ they espoused. When the dust had settled on the Morley-Minto reforms, that much was clear.

To an extent only dimly glimpsed before 1914, the political ground was heaving beneath them all. A fourth idea of India was in the making. It was less the dream of an Indian state than the anxious search for Indian community. Its prophet was Gandhi, whose

Hind Swaraj

(1909) brusquely rejected Western civilisation and Congress ideology in favour of a spiritual India of self-sufficient villages. Outside the formal world of Civilian rule and Congress politics, a host of new interests was emerging. Hindu

sabhas

,

121

Muslims,

122

caste associations, leagues of peasants,

123

even groups of workers, sought a new solidarity or defended an old. In Bengal

124

and Madras,

125

new social ambitions were afoot in the countryside. Congress's ‘British India’ meant little to such men. Regional interests and communal identities were much more pressing. Whom they would follow and to what effect were as yet unknown. The answers would come much sooner than anyone expected.

6 THE WEAKEST LINK: BRITAIN IN SOUTH AFRICA

In South Africa, the bond of empire was weaker and the strains on it much greater than in other colonies of settlement. The European whites were predominantly non-British; the indigenous blacks more numerous and resilient. The frontier wars of conquest lasted longer, were fought with greater ferocity and spread out over a whole sub-continent. For much of the nineteenth century, South Africa was viewed in London as a hybrid region: a composite of settler and ‘native’ states. Imperial policy veered unpredictably between a ‘Canadian’ solution of settler self-government and the ‘Indian’ solution of direct control – at least over the large zones where autonomous black communities survived. Partly as a result, on the white side certainly, the ‘Imperial Factor’ was regarded with profound mistrust.

South Africa was likely to be an awkward element in the imperial system at the best of times. The sub-continent was stuck in its own version of Catch-22. As long as the struggle between whites and blacks continued there could be no hope of devolving imperial authority to a settler government on the model of Canada, the Australian colonies or (most relevantly) New Zealand. The whites were too divided; and the blacks were too strong to be contained without the help of imperial troops. But every imperial effort to promote settler unity and impose a common policy towards black peoples and rulers roused fresh white animosity against London's ‘dictation’ – especially among the Afrikaner (or Boer) majority. Suspicion of the Imperial Factor was the main cause of South Africa's peculiar fragmented state structure, with its division between two colonies, two Boer republics and a scattering of black territories, some in direct relations with London through the High

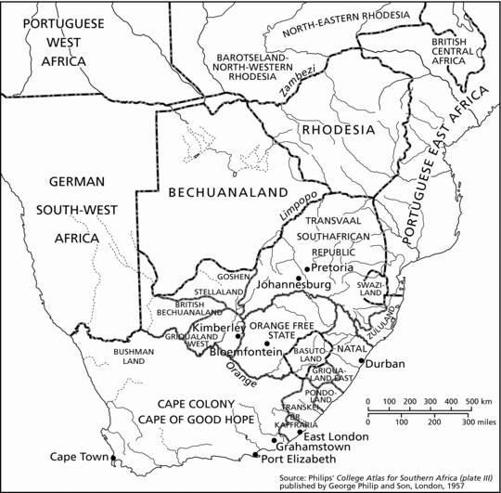

Map 8 South Africa in the nineteenth century

Commissioner in Cape Town, who doubled as the Cape Colony's governor. But, in the late nineteenth century, South Africa turned into something more than a tiresome frontier province of the Empire. It became the arena where the political and strategic cohesion of the British world-system was tested to its limit.

There were several reasons for this. In the 1880s, South African politics were transformed by the new wealth from diamonds and gold. The rapid growth of the mineral economy sucked in foreign capital and sharpened the competition for trade between the South African states. But its most disturbing effect was to create uncertainty about the geopolitical orientation of the whole region. With its gold revenues and commercial leverage as the great inland market, the autonomous Boer republic in the Transvaal now had the means to strike free from British paramountcy, dragging the rest of Southern Africa with it. But it also ran the risk of being inundated by foreign (mainly British) immigrants attracted by its new prosperity. If that were to happen, the Transvaal would become British by default, pulling the Afrikaners of the interior back into Britain's orbit, and making South Africa another Canada. The stakes were high. By the 1890s, the grand problem of South African politics seemed about to be settled. But no one could be sure what the outcome would be.

What made this regional issue into an imperial question was the intersection of South Africa's economic revolution with two wider political forces. The fate of the Transvaal, and of South Africa, turned (or so it seemed) upon the treatment of the immigrant British, or Uitlanders. The Transvaal was the high water mark of British migration, the demographic imperialism that had served so well to extend British influence, power and wealth. Kruger's republic fiercely resisted the habitual demand of British communities overseas for political and cultural predominance as the self-appointed standard-bearers of progress. But, in doing so, it set itself against a tide of British ethnic nationalism then approaching its peak. As a result, the Transvaal's relations with Britain and the rest of South Africa became entangled in the bitter ethnic rivalry of Afrikaners and ‘English’ (the usual term for British settlers in South Africa) in the prelude to war in 1899. Worse still, at the very moment when economic change was maximising political uncertainty, South Africa became the focus of imperial rivalry. As the new geopolitics of partition extended ever more widely across the Afro-Asian world, Britain's claim to regional supremacy in Southern Africa, languidly asserted since 1815, became critical to her strategic interests and world power status. This sudden conjuncture of ethnic, economic and geopolitical tensions turned South Africa, almost overnight, from a colonial backwater into the most volatile quarter of the Victorian empire.